| HOME | UP |

|

'Feeling is like

poison and a certain kind of high explosive": Joseph Pridmore

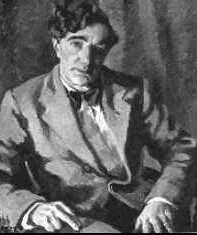

James Hanley During the First World War, two British working-class infantrymen become separated from their patrol in the trenches of France. They encounter a young German soldier who surrenders and becomes their captive. He is then savagely beaten, sexually tortured and murdered, shortly before the two British troops are themselves killed in a bombing raid. That's the premise of The German Prisoner, James Hanley's second book, and one of the most powerful, harrowing and important works he ever produced. It's unlikely that any conventional publisher would have accepted The German Prisoner in 1930, when censorship rules concerning overtly violent or gay writing were extremely severe. Two years later, publishing house Boriswood were faced with legal action when Hanley's novel Boy, which they had released the previous year in 1931, was judged an obscene libel. Boriswood pleaded guilty and were fined a total of £400, while the book itself was banned and remained so for almost sixty years. Boy, a disturbing work in its own right, deals with many of the same themes as The German Prisoner, but even so does not have the impact and overwhelming horror of Hanley's earlier work. This perhaps explains why The German Prisoner was produced as a luxury edition, with vellum pages and a gilt-stamped buckram cover, priced at one guinea, and-crucially-privately printed, to allow its unconventional content to bypass contemporary publication laws. Richard Aldington, whose financial assistance was essential in producing The German Prisoner's print run of five hundred, was a staunch supporter of Hanley's works. His introduction to the edition anticipates the objections that such a story would raise in a typical bourgeois readership, before going on to pugnaciously champion the emerging form of 1930s working-class writing to which Hanley can be said to belong: Here we see human nature ruthlessly exposed in its most abject and terrible circumstances; we see the unspeakable wrong which is worked upon human souls by those who are supposed to be its guardians and guides. Why are these men in this hell? Mr. Hanley leaves us to find the answer. But what force and vitality there are in this presentation of men driven to madness under the inconceivable stress of modern war...

Aldington's warmth and respect for Hanley is not to be questioned, and his preference for powerful, hard-hitting writing over bourgeois art-for-art's-sake recalls the sentiments expressed in his own story of World War One, The Death of a Hero (1929). (3) However, Aldington's interpretation of The German Prisoner itself is not without faults. It's not sufficient to say that the sole purpose of Hanley's text is to impress upon its readers the corruption and depravity that working class soldiers were reduced to in a war for the upper classes’ sakes. I would like to argue that Hanley wants us to understand more than Aldington's reading suggests, and that the real function of The German Prisoner is to subvert certain key bourgeois concepts associated with the Great War, thereby providing a uniquely working-class voice. The first problem with Aldington's appraisal of The German Prisoner is that if Hanley’s intention is to portray "men driven to madness by the inconceivable stress of modern war," then he has chosen a strange pair of protagonists with which to do so. Of the two British soldiers, the Irishman Peter O'Garra is the one we learn more about and it is from his perspective that the majority of the story is told. On page eight Hanley presents us with a list of no fewer than twenty-three terms of insult by which O'Garra has been known over the last fifteen years, including "Belfast bastard," "misanthrope," "sucker," "blasted sod," "strange man," "toad" and "pervert."(4) This last one is clearly justified even if the others are not, for we are told that O'Garra has a habit of stalking and frightening women back home in Ireland. (There are two references to his "lonely nights, those fruitless endeavours beneath the dock in Middle Abbey Street.") (5) But unsavoury as O'Garra seems, his Mancunian crony and squadron-mate Elston is even worse. Apparently, "When he [O'Garra] had first set eyes on Elston, he had despised him, there was something in this man entirely repugnant to him." (6) One hardly likes to think what kind of "something" could be so appalling to a man like O'Garra. But my purpose in drawing attention to all this is to argue that surely, if Hanley's intention is to show working-class men brutalised by the horrors of modern war as Aldington suggests, then why does he involve characters who seem immensely brutalised from the very beginning? Wouldn't it make more sense to portray Elston and O'Garra as more conventional working class characters, not possessed of their debased and repulsive tendencies at first, but developing them as a result of the hardships they face? John Fordham makes a similar point when he remarks that The German Prisoner "is a curious story from one whose writer's sense of mission derives from a desire for working-class emancipation, since its two soldier protagonists from the ranks are represented as unspeakably sadistic."(7) Certainly Hanley presents us with an unflinching view of their sadism in the torture scene itself, which in places becomes difficult to read. It takes some effort to look beyond the stark portrayal of violence but, if we do, we can observe two important elements that contribute much to the deeper meanings of this story. One is the strong undercurrent of homosexual desire, about which more later, and the other is the political and psychological dimensions behind the act of torture itself. Elaine Scarry’s The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World provides an attempt to theorise the politics of torture. She begins by arguing that 'To have pain is to have certainty;" or to put it another way, pain is one of the most vivid and indisputable emotional states. (8) Somebody in pain will be in no doubt as to whether they are in pain, and though they may be able to convince others that they are not, the sufferer cannot fool him or herself in this way. (9) For Scarry, the undeniable reality of pain is at the core of the political intent behind the act of torture:

This interpretation is useful in understanding the activities of Elston and O'Garra as they set about inflicting agonies on the eponymous German prisoner, Otto Reiburg of Muenchen. The two British soldiers repeatedly announce their opposition to Reiburg's leaders, countrymen and nation, thereby associating themselves with Britain and her allies in the War's greater scheme. ("We're trapped here. Through you. Through you and your bloody lot. If only you hadn’t come.")(11) In perverting the role of "defenders of the nation" Elston and O'Garra legitimate the atrocities they commit upon Reiburg, convincing themselves that their acts of violence are carried out in the name of King and country. According to Scarry, one of the functions of torture is to establish a framework of allegiance and opposition:

The warring faction that Elston and O'Garra ally themselves with can be seen as a "contestable power" or "unstable regime" in two ways. Firstly, their assertions that their deeds are only what their nation demands of them in wartime are tenuous, to say the least. They are simply two rogue soldiers in a trench, separated from all their commanding officers, acting without the orders or approval of any higher-ranking figure. What power they have over the situation in a non-military sense is also dubious, for although they successfully dominate their prisoner, both know that an untold number of enemies, hidden in the fog, have them surrounded. Their torture of Reiburg can be seen as a desperate attempt to cling to some illusion of power over the opposing faction, whilst both British troopers steadily descend into madness caused by this terrible fear for their lives. Hanley portrays their breakdown into paranoia and delusion in every graphic detail: their repeated and obsessive cries that there is no escape, their verbal and physical fights with each other, and their increasingly deranged view that Reiburg is the one personally responsible for the War and all their suffering. Just before the final torture scene in which Reiburg is killed, Elston screams at him:

The defenders of Britain and all her values are in reality no more than two madmen fearing their deaths, which duly come to them in the story's final paragraph. But the power they claim to represent is unstable for another reason, and that is because the very idea of nineteenth-century British values and the politics of Empire were thrown into question by the events of the Great War. New technology and new methods of fighting changed the way in which battles were fought, and made it dear that wars such as those previously won by the British Empire would not come again. The world had changed, and a new form of combat now brought fatality statistics so high that men were reduced to nothing but numbers. For many, a telling symbol that the old order had passed and a new, darker age was beginning was the enormous losses that were suffered among the younger generation, such as in 1916 when thousands of British youths were unceremoniously slaughtered during the Battle of the Somme. (Hanley’s elder brother Joe was among them.)(14) Events such as this led to a growing fear that the natural order had been sacrificed, and continuity and social stability were now under threat from the new, advancing class of Yeatsian "rough beasts." Otto Reiburg can be seen as an image of doomed youth after this fashion, while Hanley's descriptions of O'Garra and Elston repeatedly portray them as brutal and physically repellent. There is an abundance of animal imagery: Elston has teeth "like a horse's, "(15) O'Garra is referred to as a "rat, "(16) and the two men maul Reiburg's body "like mad dogs. "(17) Furthermore, in a descriptive passage comparing Elston and Reiburg's physical appearances, we are told that "Nature had hewn him [Elston] differently, had denied him the young German's grace of body, the fair hair, the fine clear eyes that seemed to reflect all the beauty and music and rhythm of the Rhine. "(18) In this way The German Prisoner is similar to Hanley's later short story 'Feud’, in which once again an old order represented by a beautiful youth is crushed by coarse and savage men.(19) When O'Garra (who is marginally more sympathetic than Elston) bursts into tears upon first seeing "the stream of blood gush forth from the German's mouth,"( 20 ) his weeping can be interpreted as an unconscious response to the death of civility that he is enacting. And in participating in this shift to barbarism, thereby undermining the values they claim to be upholding, the two British soldiers render the power they represent all the more contentious. The German Prisoner's gay overtones are never made explicit, as they are in the book's companion piece A Passion Before Death, but they are no less powerful for it. They emerge in various different forms throughout the text, the first of these being a suggestion of homosexual attraction between the two British soldiers themselves. This dimension is only ever hinted at, most strongly in the paragraph below when Elston and O'Garra are fleeing from the attack that will separate them from their squadron and land them in the fateful trench: And now every sound and movement seemed to strike some responsive chord in the Irishman's nature. He hung desperately onto the Manchester man. For some reason or other he dreaded losing contact with him. He could not understand this sudden desire for Elston's company. But the desire overwhelmed him. (21) When Otto Reiburg stumbles into Elston and O'Garra clutches, the story's homoerotic elements take on a stronger and much more loathsome form. Perhaps because of this unrealisable desire between the two British troopers, or perhaps because O'Garra (as we know from the accounts of his activities on Middle Abbey Street) is already sexually frustrated, their torture of Reiburg rapidly becomes as lascivious as it is violent. From his first appearance, perceived through the eyes of Elston and O'Garra, Reiburg is described in romantic, sensuous terms: Hanley dwells upon his body, "as graceful as a young sapling," his hair, "as fair as ripe corn," his "blue eyes, and finely moulded features. As the torture progresses, Hanley remarks of Elston that "There was something terrible stirring in this weasel's blood. He knew not what it was. But there was a strange and powerful force possessing him, and it was going to use him as its instrument. (23) We see this force at work during Elston and Reiburg's moments of physical contact during the violence, which are strongly erotic in tone. ("Elston, on making contact with the youth's soft skin, became almost demented. The velvety touch of the flesh infuriated him.," (24)) What follows is the final segment of the torture scene, in which the death-blow is struck:

Here the dimax of the torture scene parallels the climax in a sexual act. Overt gay elements are prominent: the repeated use of the word "bugger," the fixation on Reiburg's anus and penis, and Elston's remark about "back-scuttling" leave us in no doubt that homosexual desire is apparent here. (Shortly after this scene, Elston remarks, apropos of nothing: The last time I fell asleep I did it in my pants. It made me get mad with that bugger down there. Though we're not told what exactly he did in his pants, the most likely suggestion for a man Elston's age would be a nocturnal emission, prompted by his attraction to Reiburg, which he dealt with through the torture that followed.) The scene also contains some more oblique gay symbolism: the bayonet "enters" Reiburg as a phallus would, and the event that this leads to his death is described in language that recalls the "little death," or orgasm. Hanley presents the violence committed by Elston and O'Garra in a manner that acts out, with monstrous transformations, the practice of homosexual congress. In The Body in Pain, Elaine Scarry describes this transformation as one of the key elements of torture. In order to objectify the disappearance of anything in the world external to the victim's pain, "Everything human and inhuman that is either physically or verbally, actually or elusively present.. .become[s] part of the glutted realm of weaponry; weaponry that can refer equally to pain or power. (27) The human body can become a weapon against itself if contorted or abused; language becomes a weapon through verbal connection with non-present objects (there are torture methods called The submarine," "the Vietnamese tiger cages," "the parrot's perch" etc.),(28) and torturers are known for taking everyday objects not intended for violent purposes and using them as instruments for doing harm. (29) Elston and O'Garra's weapon is a bayonet, an object designed to cause injury, but it's still possible to see something of the transformation Scarry describes in the metaphorical process whereby the male phallus becomes a steel blade. Through the symbolic metamorphosis of the one to the other, an organ that should allow the ultimate sharing of human experience (the sensations of sexual intercourse) instead brings a completely internal experience that the two other men do not share (Reiburg’s pain). Of course, as Hanley is well aware, homosexuality played an important part in the lives of many British soldiers of the First World War and informed much of the writing they produced. Paul Fussell remarks that young middle- and upper-class officers, coming to the front line from public school and used to life without female company, found comfort and satisfaction in a tender, romantic, sublimated and temporary homoerotic desire that recalled the crushes on older boys of their earlier adolescence.(30) Fussell states that gay writers of the Great War such as Wilfred Owen called upon a literary tradition that portrayed soldiers as homosexually desirable, dwelling on their youth, virility, cleanliness and heroism. The original source for writing of this nature is the Classical texts of Greece and Rome, but its modem-world equivalent can be said to begin with Whitman, followed by Hopkins and Housman and continued in the immediate pre-War years by the Aesthetic movement and the Uranians.(31) This pre-existing tradition informed the front-line homoerotidsm identified by Fussell, which he recognises as a purely bourgeois interest. Of working class infantrymen he makes no serious mention, and is content to remark in passing that "Of the active, unsublimated kind [of homosexuality] there was very little at the front. "(32) The German Prisoner focuses on a very different social class, and a very different type of homosexual activity, to the one Fussell concentrates solely upon. However, there's a strong suggestion of the young, desirable and chaste soldier ideal in Reiburg himself, whose blond hair, extreme physical beauty and (initially) unsullied aspect are all characteristics the Uranians and Aesthetics sought in such a figure. By presenting Reiburg as an object not of some romantic, unfulfilled desire but rather of a violent desire that manifests itself in physical brutality and murder, it's as if Hanley is challenging the sexual ideals associated with upper-class officers just as he challenges the ideals they were supposed to be fighting for. The German Prisoner is a story that overturns all our assumptions about the Great War and the men who fought in it, providing a working-class perspective that is very different; so different it is often unsettling to read, but which remains unflinchingly expressive throughout. Hopefully all this illustrates the flaws in Richard Aldington's view that Hanley's story presents the working class simply as victims; innocent pawns unspeakably corrupted when forced to endure hell in the name of the social order above them. Rather, Hanley's work is deliberately subversive-it unbalances established bourgeois beliefs about the War and presents the experiences of those whose voices have been excluded from histories of the event, which have for the most part been documented by and for the middle and upper classes. Hanley's working class soldiers are not pleasant men to read about, but it is not his point that they should be, any more than he intended for us to see them as sufferers under a higher power. Hanley's aim is to provide an authentically working-class voice, one that we may not always want to hear, but which will nonetheless be heard over the bourgeois voices that surround it. Aldington's introduction comes closest to Hanley's original intent at its very end, when he writes: Gentlemen! Here are your defenders, ladies! Here are the results of your charming white feathers. If you were not ashamed to send men into the war, why should you blush to read what they said in it? Your safety, and indeed the almost more important safety of your incomes, were assured by them. Though the world will little note nor long remember what they did there, perhaps it will not hurt you to know a little of what they said and suffered. (33)

Notes 1) John Fordham, James Hanley, Modernism and the Working Class, Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2002, p. 146. 2) Richard Aldington, 'Introduction’, in James Hanley, The German Prisoner, privately printed by author, 1930, pp.4-5. 3 J Fordham, p.97. 4) Hanley, p.8. 5) Hanley, pp. 22-3. 6) Hanley, p. 10. 7) Fordham, p.96. 8) Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985, p. 13. 9) Scarry,p.4. 10) Scarry, p.27. 11)Hantey,p.32. ^ 12)Scarry,p. 52. 13)Hanley,p.31. 14) Fordham, p. ix. 15) Hanley, p. 29. 16)Hanley,p.27. 17) Hanley, p. 32. 18) Hanley, p.32. 19)Fordham, p.99. 20) Hanley, p. 27. 21)Hanley,p. 18. 22)Hanley, p.24. 23) Hanley, p. 25. 24) Hanley, p. 32. 25) Hanley, pp.32-3. 26) Hanley, p.33. 27 )Scarry, p.56. 28) Scarry, p. 44. 29)Scarry,p.41. 30) Paul Fussell, The Great War and Modem Memory, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975, pp.272-4. 31) Fussell, pp.281-3. 32) Fussell, p. 272. 33) Aldington, in Hartley, p.5.

Bibliography Aldington, Richard. The Death of a Hero, London: Chatto & Windus, 1929. Fordham, John. James Hanley, Modernism and the Working Class, Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2002. Fussell, Paul. The Great War and Modern Memory, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1975 Hanley, James. A Passion Before Death, privately printed by author, 1930. Hanley, James. Boy, London: Boriswood Ltd., 1931. Hanley, James, 'Feud’ in Men in Darkness, London: John Lane The Bodley Head, 1931. Hanley, James. The German Prisoner, privately printed by author, 1930. Scarry, Elaine. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985. Stokes, Edward. The Novels of James Hanley, Melbourne: Cheshire, 1964.

|