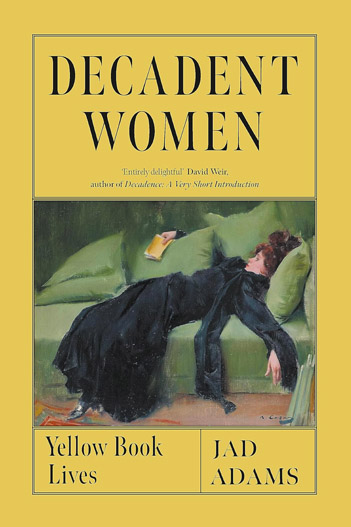

DECADENT WOMEN : YELLOW BOOK LIVES

By Jad Adams

Reaktion Books. 388 pages. £20. ISBN 978-1-78914789-6

Reviewed by Jim Burns

The Yellow Book

has a special place in the history of nineteenth century British literature,

and in any chronological survey of literary magazines. From a literary point

of view it represented a change in the direction that writing was taking as

the century drew to a close and new ideas and influences began to alter the

shape and substance of novels, short stories, and poems. These changes were

not always welcome and blistering attacks came from conservative quarters.

Decadence, a word that can suggest various things, from personal waywardness

to national weaknesses and failings, was soon often a term applied to

whatever the speaker found objectionable. This might cover foreign

influences and the increasing independence of women. Jad Adams quotes the

critic Hugh Stutfield: “Decadence is an exotic growth unsuited to British

soil, and it may be hoped that it will never take permanent root here.

Still, the popularity of debased and morbid literature, especially among

women, is not an agreeable or healthy feature”.

It should be noted that I referred to

The Yellow Book as a literary magazine. It can hardly be called a little

magazine of the kind that became familiar in the twentieth century, when

they came in all sorts of shapes and sizes and frequently disappeared as

quickly as they appeared. The Yellow

Book really was a book. I’m looking at a somewhat battered copy dated

April 1895 that I found on a

stall outside a second-hand bookshop around sixty years ago. It has hard

covers and runs to over three hundred pages. And it was published by John

Lane at the Bodley Head. An additional fact that might give an indication of

who the readers were likely to be is that it cost five shillings per issue.

That was quite a tidy sum at a time when a weekly wage of thirty shillings

or so would have been considered acceptable.

The Yellow Book

did have a relatively short life – thirteen volumes between April 1894 and

April 1897 – and the reasons for its demise were inevitably financial. It

was not a publication destined to achieve the kind of sales that would make

a profit. There was also the effect of the scandal surrounding Oscar Wilde’s

arrest in 1895. Newspaper reports said that he was carrying a “Yellow Book”

with the implication that it was a copy of

The Yellow Book”. It was, in fact

a French novel, Aphrodite by

Pierre Louys, which was bound in yellow covers, but the damage had been

done. Opponents of what they claimed

The Yellow Book stood for - decadence -

very quickly worked up outrage and indignation against it and some of

its contributors. Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations were

particularly picked on for their alleged salaciousness. Even some

contributors to The Yellow Book

thought it necessary to disassociate themselves from any links to Beardsley.

William Watson said “Withdraw all Beardsley designs or I withdraw my books”,

meaning those published by the Bodley Head. And Mrs Humphrey Ward, a popular

Victorian novelist, also spoke against Beardsley. John Lane later claimed

that “The Wilde scandal “killed The

Yellow Book and it nearly killed me”, but that was an exaggeration. It

survived for nine more issues.

The reference to Mrs Humphrey Ward brings me to what Adams is concerned to

deal with – the role of women as contributors to

The Yellow Book, and in some

cases in its editing. He makes the point that “Women made little or no

appearance in such accounts of the period as

Men of the Nineties or

The Beardsley Period, yet the

most cursory examination of contemporary material shows that women were

everywhere writing novels, short stories and poems, selling and being

reviewed at the same level as the men”. And he adds that “A third of the

writers of the Yellow Book…….were

women”. It occurs to me to point to a couple of anthologies of

Yellow Book writing to see how

women were represented. The Yellow

Book: A Selection, edited by Norman Denny (Spring Books, London. n.d.)

has six women out of thirty contributors, and

The Yellow Book, edited by Fraser

Harrison (The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 1982) has three out of fifteen. I

may have missed one or two where a woman published under a male name. Times

may have been slowly changing, with the ”New Woman” asserting herself, but

there were still some who disguised their identity. I also checked

Poetry of the Nineties edited by

R.K.R.Thornton (Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1970) where there are five

women (I’ve counted “Michael Field” as two) out of thirty-three

contributors.

George Egerton - Mary Chavelita (Dunne) Bright -

was one woman who chose to use a male name. She was born in Australia

in 1855, lived in Ireland and Germany, and was in New York for a time. She

also visited Chile and worked in London as a nurse. But, “After decades of

struggle in different countries and at different jobs, still earning nothing

but the bare minimum to keep alive, Chavelita realised she must take her

chances where she could”. She ran away with a bigamist called Henry

Higginson. They went to Norway where Higginson died and Egerton had an

affair with Knut Hamsun, whose novel,

Hunger, she translated into English. She also became familiar with the

work of Ibsen and Strindberg. When she returned to London she began to write

in order to earn some money. And she did so as George Egerton, the name

being partly concocted from that of Clairmont Egerton, “one of those

feckless wastrels to whom she was so attracted”.

It was as George Egerton that John Lane published

Keynotes, a collection of short

pieces that Adams rates highly. He refers to the critic Camilla Prince’s

description of it as “literary impressionism”, and says Egerton was

influenced by Hamsun: “She developed an internalised style similar to his,

with similar disregard for narrative conventions.”. Her work had

“distinctively modern

characteristics : subjective impressions, fragmented structures,

plotlessness, capturing an impression of a floating time or

place, engaging dreams or reveries, focusing on minute details,

employing a fragmented chronology and showing an interest in psychology”.

Egerton’s work also raised “uncomfortable questions about sexual

attraction…….why a refined, physically fragile woman will mate with a brute,

a mere male animal with primitive passions”. It’s easy to see why the

combination of stylistic innovations and down-to-earth subject-matter

disturbed readers more used to the polite meanderings of much nineteenth

century literature. Another Egerton collection of stories,

Discords, “dealt with alcoholism,

violence and suicide” and was “criticized from the usual quarters for

portrayals of female drunkenness and frank depictions of sexuality”.

One of the advantages of Decadent

Women is that Adams divides his book into two sections, the first

dealing with the writers’ activities before and during their

Yellow Book period, and the

second looking at what happened to them in later years. It wasn’t all wine

and roses. Egerton went to Norway in 1899 for what Adams refers to as “her

next adventure” which was with a Norwegian student “fifteen years her

junior”. He was “depressive, frequently threatened suicide, and was under

the control of his parents who had plans for him”. When this relationship

didn’t work out she returned to England and struck up another, again with

someone fifteen years younger, Reginald Goulding Bright.

They married in 1901. Bright was “a

journalist, a drama critic who was working towards becoming a theatrical

agent”. Egerton tried her hand at writing plays but without any great

success. Her later years saw her mostly forgotten as a writer, and Adams

says that when her husband died in 1941, she was in financial difficulties,

and “sold many of her books and most of her furniture. She went to live in

boarding houses but was not popular” with other residents. She died in 1945.

I’ve only sketched in some basic details and have omitted a great deal of

information that Adams supplies.

Ella D‘Arcy was another writer who had a bright beginning but died in

obscurity in 1937. Adams says that she “studied at the Slade School of Art

for two years, making her one of a number of

Yellow Book writers who also

pursued a career as an artist, but poor eyesight made her abandon this

career”. She’s probably mostly

read these days for a handful of short-stories. One of them, “Irremediable”,

concerns a bank clerk who encounters a working-class girl from Whitechapel,

a notorious slum area in the 1890s. An earlier unhappy relationship with a

more-sophisticated woman has inclined him to link “ideas of feminine

refinement with those of feminine treachery”, and he initially warms to the

seemingly-more sincere and down-to-earth attentions of the girl. They marry

“on his £130 a year. The story then finds him with a slatternly wife in a

house ‘repulsive with disorder’ ”.

She evinces “all the self-satisfaction of an illiterate mind”, while

he “pines for his bachelorhood of books and solitude”. It’s a story about

class, and D’Arcy nowhere shows any sympathy with the wife. Adams says she

“presents a sour view of women that is rather more complex than that

proposed by the feminists such as Mona Caird, who were battling against male

domination in marriage”.

D’Arcy worked as an editorial assistant at

The Yellow Book for a time, but

fell out with its editor, Henry Harland. She wrote a novel based on the life

of Shelley but it remained unpublished. She really didn’t have much of a

literary life after The Yellow Book

folded, and Adams says: “At the end of the century she left London’s

hissing gas lamps and fog for a new lease of life in the French capital”.

There may have been other reasons for her failure to develop her writing and

establish a reputation and career in the literary world. Netta Syrett, a

fellow-contributor to The Yellow Book,

claimed that D’Arcy didn’t prosper because of her “incurable idleness”.

There isn’t a great deal of

information about her life in Paris, though she did associate with Gertrude

and Leo Stein, and she worked on an unpublished biography of Rimbaud. She

returned to London in 1937 after suffering a stroke. Because

of her impoverished financial state she was taken to the infirmary of

St Pancras Workhouse, where she died

in September 1937.

The lure of Paris, and the attractions of French literature, come to the

fore in a chapter entitled “A Paris Mystery” which deals with the strange

death of Hubert Crackanthorpe, a key contributor to

The Yellow Book. I have to admit

to a particular interest in Crackanthorpe, having long-admired his short

stories. He had married a minor and now-forgotten poet called Leila

MacDonald, who had also published in the magazine. They’re side-by-side in

the old copy that I have. Both were from well-to-do families. As Adams puts

it: “The Crackanthorpes were the golden couple that everyone wanted to be:

they were both good-looking, wealthy, upper-class, well-connected,

well-travelled and talented”.

It might have seemed that nothing could go wrong.

However, in 1896 Crackanthorpe mysteriously disappeared while out for a walk

in Paris. His body was recovered from the Seine some weeks later. There were

rumours regarding promiscuity by both parties and suggestions that syphilis

had been passed on by one or other of them and another couple with whom they

were involved in some sort of sexual arrangement. Adams tells the complete

story, and I’m only summarising, but suffice to say that it created

something of a scandal in its day. It convinced those who disliked the

decadents that their habits, and their love of Paris and French literature,

could only lead to moral breakdown and its consequences. Leila MacDonald

published one book, The Wanderer and

Other Poems, in 1904 but otherwise appears to have completely

disappeared from the literary world. She died in Paris in December, 1944.

I’ve only skimmed the surface of the range of women Adams covers in his

survey of their links to The Yellow

Book and their later lives. I could have looked at others whose

activities pointed to their activities and involvements, and their problems

getting published and acknowledged in a society still dominated by men.

There was Gabriella Cunningham-Graham : “a friend of Oscar Wilde, W.B.

Yeats, William Morris and Keir Hardie. She was known for speaking on

international platforms for radical causes, giving lectures on socialism and

mysticism, writing a major biography of St Teresa and contributing to the

Yellow Book”. She claimed to have

been born in Chile to a French father and a Spanish mother, and to have

spent time in a convent school in Paris when she was orphaned. She was, in

fact, Carrie Horsfall, a doctor’s daughter from Yorkshire, who had run away

from home at sixteen to become an actress in London. Adams suggests that,

before marrying the socialist politician Robert Cunningham-Graham, she may

have had a relationship with an older man who took her to Chile, hence her

familiarity with the country and her command of Spanish.

Decadent Women

is a valuable book from the point of view of bringing to light numerous

facts about the lives of a selection of neglected writers. And in some cases

hopefully arousing interest in what they wrote. Jad Adams has clearly done a

lot of research to come up with some of the information he provides. There

are almost forty pages of notes, a short but useful bibliography, a number

of appropriate illustrations, and a list of all the women who were published

in The Yellow Book. In some ways

Decadent Women is almost a

partial history of the journal, and as such it will find a place on my

bookshelves alongside Katherine Lyon Mix’s

A Study in Yellow : The Yellow Book

and its Contributors (Constable, London, 1960). Both are essential for

anyone who considers their subject-matter of interest.