|

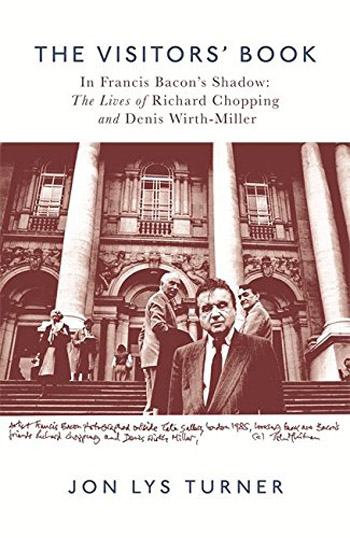

THE VISITORS’ BOOK: IN FRANCIS BACON’S SHADOW: THE LIVES OF RICHARD CHOPPING AND DENIS WIRTH-MILLER By Jon Lys Turner Constable. 392 pages. £20. ISBN 978-1-47212-166-0 Reviewed by Jim Burns

Now that Soho is no longer the shabby but lively area it once was, and has perhaps largely lost its reputation as a bohemian enclave, it may be inevitable that more books will appear celebrating its golden days. The period from the mid-1930s through to the mid-1980s might be seen, in retrospect, as one when numerous artists, writers, and others, congregated, first in Fitzrovia, the area to the north of Oxford Street and on the west side of Tottenham Court Road, and then Soho, to the south of Oxford Street and on the west side of Charing Cross Road, and talent abounded. Some will, no doubt, question the dates I’ve mentioned, but I think I’m reasonably accurate in suggesting that, by the 1980s, the old idea of bohemia was declining. Observers of bohemia might say that its oncoming death was noticeable before then, and that it was the commercialised pop scene of the 1960s that finally killed it off. But I’ll leave the question of whether or not bohemia still exists, other than in the minds and actions of individuals, for another time. Jon Lys Turner hasn’t set out to provide a history of bohemian London, but as the central characters, and many of the rest in his book, all spent a fair amount of time in Fitzrovia and Soho, it’s guaranteed that it will add to the library of publications which, in one way or another, revolve around the subject. The name of Francis Bacon in the title will, of course, attract the required attention, but it will be a pity if most of the others mentioned, including Richard Chopping and Denis Wirth-Miller, are overlooked or dismissed as of no interest. It is true that, in the larger scheme of things, Chopping and Wirth-Miller were comparatively minor artists. Neither did anything likely to change the direction of art, but in their day they both produced work that had something worthwhile to offer. They met in the 1930s – Turner says they encountered each other in the Café Royal on Regent Street, then a fashionable place for more-affluent artists and writers to congregate. Not that they were particularly well-off. Chopping was from a comfortable middle-class home and had a good education, whereas Wirth-Miller had a more basic background (his parents ran what is described as a “down-market hotel), an unsettled childhood, and little extended formal learning. They were both homosexual and soon formed a partnership that was to last for the rest of their lives, albeit with more than a few ups and downs along the way. They quickly got to know other artists, among them Augustus John, William Coldstream, Lucien Pissarro, and Nina Hamnett. She had been around the Paris bohemian scene in earlier years, and her book, Laughing Torso, published in 1932, and reprinted by Virago in 1984, is a lively account of her encounters with Picabia, Picasso, Modigliani, and many others. She was a talented artist, but by the late-1930s was beginning a descent into the alcoholism that would blight her later years when she became a character around the pubs and clubs of Soho. A later book, Is She a Lady? (Wingate, 1955) is fragmentary, but interesting, and perhaps shows the influence of her increasingly dissipated life-style. Denise Hooker’s Nina Hamnett: Queen of Bohemia (Constable, 1986) is informative about her, and Hooker says that Is She a Lady? was “rambling, disjointed and inconsequential, a sad reflection of Nina’s own state.” There were others that Chopping and Wirth-Miller met, including the poet Anna Wickham, and the Scottish artists, Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde who were, like them, life-long partners and prone to drinking too much and falling out. Roger Bristow’s The Last Bohemians: The Two Roberts – Colquhoun and MacBryde (Sansom & Co., 2012) tells their story. Chopping and Wirth-Miller soon moved to Soho and the Gargoyle Club where they came across John Minton and Francis Bacon. Turner provides some background information for both, though Bacon has been extensively written about elsewhere, and Minton, if not as well-known, has had at least one book devoted to him (see Frances Spalding’s Dance till the Stars Come Down, Hodder & Stoughton, 1991), and crops up in accounts of the London art scene of the 1940s and 1950s. By this time Chopping had begun to attract some attention when a couple of his paintings were in an exhibition alongside works by Lucien Pissarro, John Nash, Jacob Epstein, and Duncan Grant. But when the war started in 1939 he was called up for service in the army. Chopping was eventually discharged from the Forces on medical grounds and he and Wirth-Miller resumed their activities. It’s obvious that the main purpose of Turner’s book is to tell the story of how the couple related to Bacon, and in particular how Wirth-Miller got along with the more-famous artist. Chopping, though a heavy drinker and sexually promiscuous, wasn’t much inclined towards Bacon’s approach to art or life. But, as I said earlier, it would be a pity if his work, and that of Wirth-Miller, was ignored simply because it didn’t match up to Francis Bacon’s paintings. Chopping became quite successful with illustrations for children’s books and for those about natural history. You can still pick up copies of the book he did about British butterflies. And, a little time later, he achieved a degree of minor fame for the covers he designed for several of Ian Fleming’s James Bond books. Wirth-Miller probably never achieved great success as an artist, and was fated to always be dominated by Francis Bacon. They spent a lot of time in each other’s company, both in London and at the Storehouse, the property that Chopping and Wirth-Miller had bought in Wivenhoe. Turner has stories of them painting together and consequently creating problems for later researchers trying to decide if some of Bacon’s canvases could have had contributions from Wirth-Miller. Also, it would seem that, in more recent years, collectors and others, perhaps wanting to make a financial killing, or possibly a name in the art world, have bought canvases by Wirth-Miller and scraped off the top layer of paint in the hope that there may be a Bacon painting underneath. He was known to have left unfinished paintings at the Storehouse that Wirth-Miller possibly painted over. It would be unfair to dismiss Wirth-Miller as simply a crony or follower of Francis Bacon. His work was in an exhibition, British Landscape Paintings, at the Lefevre Gallery in 1944. As Turner puts it: “There was no better commercial gallery in London at that time for his debut. The association gave him validity as an up-and-coming artist.” And it’s worth quoting Turner again on Wirth-Miller’s paintings: “He was already developing non-narrative landscape at this time. The mood of the works may suggest a threat from nature, which would become more obvious in the darker, later paintings, but no story is explicit. The works are deliberately unpopulated and consciously full of movement: they are a moment and not a narrative in the manner of Constable’s The Haywain. The only storyteller is the viewer.” Turner, referring to the post-war bohemia in London, mentions the Colony Room Club on Dean Street in Soho. Opened in 1948, it soon became a notorious hang-out for Francis Bacon, the photographer John Deakin, John Minton, and Wirth-Miller. When Chopping was taken to the Colony Room he quickly came to see it as a “hellhole,” a description that quite a few others may have agreed with. There are any number of reminiscences of the drinking and bickering and worse that went on in the Colony Room, though Bacon appears to have thrived on the atmosphere of verbal aggression that, if various accounts are to be believed, was the norm as the nights wore on and drinks were downed. Sophie Parkin’s The Colony Room Club, 1948-2008: A History of Bohemian Soho (Palmtree Publishers, 2012) provides a useful account of the club. It’s also worth referring to Robin Muir’s Under the Influence: John Deakin, Photography and the Lure of Soho (Art Books Publishing, 2014). Despite the drinking, Chopping and Wirth-Miller were busy with their respective projects. Chopping got good reviews for work in the Royal Academy Summer exhibition in 1952, and his paintings were also on show at the Hanover Gallery. As a result, he received commissions for portraits. And Wirth-Miller had successful exhibitions at the Beaux Arts Gallery in 1956 and 1958. They were not short of money and Wirth-Miller turned out to be an imaginative speculator on the Stock Exchange and added to their overall income. He went on a trip to Tangier with Bacon, while Chopping indulged himself closer to home with various male friends. His behaviour, which he was always quite open about, didn’t seem to initially affect their relationship, though Turner does say that it “was sowing the seeds of further problems.” Wirth-Miller’s association with Bacon appears to have been based on shared interests in drinking and painting and was not necessarily sexual. As the 1950s progressed attention switched from the Neo-Romantic movement in British art and painters like the two Roberts, Minton, Keith Vaughan, Robin Ironside, and John Craxton, to the so-called Kitchen Sink school, the more abstract artists associated with St Ives, and the abstract expressionists from the United States. Pop Art was also starting to make itself known. Chopping and Wirth-Miller, never perhaps at the forefront of artistic activity, found themselves beginning to be forgotten. Bacon, of course, was too big a name by this time and individual enough to be able to withstand attempts to dismiss him along with others active in the 1940s and early-1950s. There were casualties, too, among the Soho bohemians. Nina Hamnett died in 1956 after throwing herself from her upstairs flat onto some railings. John Minton committed suicide in 1957. Robert Colquhoun died in 1962 as a result of his alcoholism, Robert MacBryde was killed in an accident in 1966, probably while drunk. Keith Vaughan killed himself some years later. Wirth-Miller’s landscapes were still arousing a certain amount of interest, and thanks to his friendship with the fashionable interior designer, David Hicks, they were recommended to the well-to-do as suitable for hanging in their houses, Chopping, in the meantime, had started to devote more time to writing, and his first novel, The Fly, was published by Secker & Warburg in 1965. It sold quite well, but a second one, The Ring (Secker & Warburg, 1967), which was about the homosexual underworld in London, was less successful. A third novel was rejected and remained unpublished. It’s Turner’s contention that bohemia, or at least the bohemia that Chopping and Wirth-Miller thrived in, was dead by 1967. Fitzrovia was for tourists hoping to catch sight of the ghost of Dylan Thomas. It was no longer associated with anything new or interesting in British art. As for Soho, it was “still a place for hard drinking and sexual antics, but the likes of the Colony Room were no longer attracting young artistic transgressors; it was the same old faces, increasingly alcoholic, their lives more chaotic.” Chopping and Wirth-Miller continued on their own merry-go-round, though not always in London. Their house in Wivenhoe was a centre for visitors and partying was often in progress. Chopping had obtained a position at the Royal College of Art, though teaching creative writing, but almost lost it when his drinking caused some embarrassment. And Wirth-Miller continued to follow Francis Bacon around as the two drank and argued. There was one terrible experience when he had an exhibition at the Wivenhoe Arts Club. Bacon, by this time famous with exhibitions in London, Paris, and New York, was invited to the opening, turned up drunk, and proceeded to laugh and make disparaging remarks about the paintings. As a result Wirth-Miller, never the most confident of people with regard to his own work, gave up painting and spent the rest of his life drinking, travelling, and becoming increasingly violent towards Chopping. Their arguments, often conducted in public, caused a lot of old friends to stop associating with them. Their final years were not happy ones, with Chopping suffering from ill-health and Wirth-Miller becoming increasingly senile: “Chopping had made friends with a younger set of people, but he was sentimental about the past, about being part of a bohemia that seemed capable of rearranging the universe, and about the old friends from that time, now deceased. Wirth-Miller, meanwhile, retreated further into his troubled memories: his treatment as a child, his imprisonment, and his final failure as an artist.” The reference to “imprisonment” relates to a conviction for “gross indecency” in 1944 when homosexuality was illegal. Francis Bacon had died in 1992, and Chopping and Wirth-Miller had been approached by journalists who wanted information about him. They refused to co-operate with them, and even turned down Daniel Farson who was working on a biography of Bacon. Farson had, after all, been a part of the Soho bohemia of the 1950s and beyond (see his Soho in the Fifties, Michael Joseph, 1987), so might have expected to be given a more positive response. Chopping had been writing an autobiography for many years, though it was never completed, and that may have had insights into their friendship with Bacon. Farson’s book, The Gilded Gutter Life of Francis Bacon (Vintage, 1993) mentioned Chopping and Wirth-Miller a few times, but the latter claimed that it was full of inaccuracies. Richard Chopping died in 2008 and Denis Wirth-Miller in 2010. It surprises me that both, like Bacon, lasted so long, bearing in mind their chaotic life-styles. It’s understandable that they resented the fact that when journalists contacted them they only wanted to talk about Francis Bacon or Ian Fleming. Both Chopping and Wirth-Miller had produced some work of value, and rightly thought they ought to be credited for it. But they’re probably now fated to be footnotes in books about Bacon or Lucien Freud. They had known Freud in their younger days but had fallen out with him. They’ll be remembered in connection with him because of a painting that Wirth-Miller gave to Jon Lys Turner. It was said to be an early example of Freud’s work, though the painter always denied that it was. But a recent BBC TV documentary seems to have established that it was, at least in part, painted by Freud when he was a very young student at the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing. Chopping and Wirth-Miller were also there at the same time. There’s no getting past the fact that, had it not been for the Francis Bacon connection, The Visitors’ Book (the title refers to the guest register at The Storehouse in Wivenhoe) might never have been published. And that would have been a pity because it provides a fascinating picture of a period in British art, the 1940s and 1950s, that has been neglected in recent years. The bohemian capers and tragedies have sometimes been written about, but too much of the art has been overlooked. It wasn’t all just Bacon and Freud. I remember the splendid exhibition, A Paradise Lost: The Neo-Romantic Imagination in Britain, 1935-55 at The Barbican in 1987. Malcolm Yorke’s The Spirit of Place: Nine Neo-Romantic Artists and their times (Constable, 1988) followed. In 2002 The Barbican had Transition: The London Art Scene in the Fifties, with an informative book using the same title (Merrell Publishers Ltd) by Martin Harrison accompanying it. Robin Ironside: Neo-Romantic Visionary was an exhibition in Chichester and Chester in 2012. And the two Roberts (Colquhoun and MacBryde) had an exhibition devoted to their work at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, 2015. I’ve used a few examples to indicate how much was happening in the 1940s and 1950s when Richard Chopping and Denis Wirth-Miller were active. And, for all its follies and foibles, there was a productive bohemia.

|