|

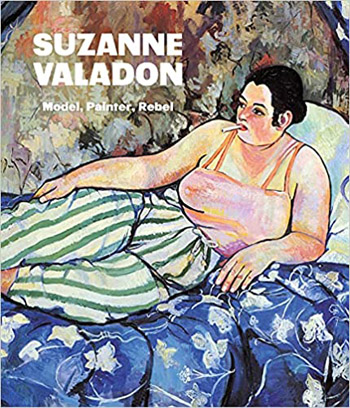

SUZANNE

VALADON : MODEL, PAINTER, REBEL

Edited by Nancy Ireson

Paul Holberton Publishing. 159 pages. £35. ISBN 978-1-913645-13-7

Reviewed by Jim Burns

Establishing a reputation in the art world has never been an easy

process, especially for women artists. And it must have been

particularly difficult for a woman aspiring to be a painter to

succeed in the competitive and male-dominated art world of

late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Paris. That Suzanne

Valadon, despite coming from a poverty-stricken background and

having had no formal art training, became a talented and

critically-acknowledged painter is a remarkable story of natural

skill allied with perseverance.

Valadon was born in 1865 and christened Marie-Clémentine Valadon.

She was brought up in Paris by her mother, and by the age of

fourteen was employed at a series of low-paid jobs, such as a

waitress and a seamstress. She was rumoured to have worked as an

acrobat in a circus at one point, though this has never been proven,

and Valadon was not averse to embroidering the facts of her life

when interviewed in later years. One of her occupations involved

delivering laundry around Montmartre, including to the artist,

Toulouse-Lautrec. It’s said that he nicknamed her “Susanna” after

the Biblical story of Susanna and the Elders. Did this happen after

Valadon began to model for Lautrec, and possibly became his lover?

It may have been his oblique comment on older artists viewing a

naked young girl.

One of the Lautrec paintings reproduced in this book is a splendid

portrait of a twenty-year old Valadon. But it’s relevant to point to

Lautrec’s “The Hangover” which shows a somewhat bedraggled woman

seated at a table with a glass and a bottle of wine in front of her.

In other words, she was a model and Lautrec could make use of her as

he wanted to obtain an effect on canvas. But, in contrast, there is

“Young Woman at a Table”, with a tidier and fresher-faced female

(modelled by Valadon) gazing into space.

Lautrec wasn’t the only Parisian painter Valadon posed for.

She modelled for Puvis de Chavannes and Pierre-August Renoir,

and it’s more than likely had sexual relations with both. Whatever

else she talked about she didn’t ever divulge who she had slept

with. It’s perhaps true to say that it is the paintings by Renoir

that are best-known in terms of the presence of Valadon. Catherine

Hewitt’s biography of Valadon,

Renoir’s Dancer: The Secret

Life of Suzanne Valadon (Icon Books, 2017) has his “Dance at

Bougival” on its front cover. And it has been reproduced widely on

calendars and posters.

Lesser-known but striking in their way are the Spanish painter

Santiago Rusinol’s “Laughing Girl” (1894) and Jean Eugene Clary’s

“Portrait of Suzanne Valadon Age 20” (1885). Both are in the book,

and I have to say that I was immediately taken with the charm of the

Rusinol. It must have been painted towards the end of her career as

a model. She gave it up when she married a businessman, Paul Mousis,

in 1896. The laughing girl is leaning forward and looking directly

at the viewer, as she must have looked directly at Rusinol, and the

look on her face is infectious. The Clary catches her only in

near-profile, but is an attractive fashionable painting.

How did Valadon get started on her own career as an artist? She had

been drawing since the age of nine, though without any sort of

encouragement. It was only when she encountered Lautrec, watched him

working, and then showed him some of her drawings, that matters

began to improve. Lautrec is said to have commented to a friend,

“She arrived at this result without taking a lesson from anybody,

ever, eh? It’s marvellous”. And another friend told him to show the

drawings to Degas. He had a reputation as a harsh critic, but became

a supporter of Valadon’s work. It needs to be recorded, too, that

she took note of Renoir’s use of colour when she posed for him.

In 1893, when Valadon was eighteen, she gave birth to a son who was

to become the painter, Maurice Utrillo, famous for his evocative

pictures of the streets of Montmartre. He was also to become

notorious for his drinking. Valadon never acknowledged who was the

father. All that is known is that, in 1891, the Spanish painter,

Miguel Utrillo, gave Maurice his surname, though it’s unlikely that

he was his actual father. Nancy Ireson says: “ Nineteenth century

men often viewed female models as easy conquests. Valadon did not

speak about her intimate relationships with those for whom she

posed, but it is likely that the boundaries between will and

obligation were blurred”.

Valadon’s marriage to Paul Mousis was over by 1910, and she had, in

fact, started an affair with André Utter, a much younger man who was

a friend of her son. And it was around this time that, because she

was making only a little money from the sale of drawings and prints,

Valadon began to paint seriously in oils. Her 1912 “Family Portrait”

focuses on herself, her elderly mother, a confident-looking Utter,

and a somewhat morose-looking Utrillo. The painter is central to the

picture and her firm presence suggests that she is the one who holds

the family together in more ways than one. To which Ireson wryly

comments: “Consequently, while Valadon’s early canvases are in many

ways progressive, they also perpetuate pre-existing notions of how

women should appear in paintings. A woman cares for her partner,

son, and mother, she is at the heart of the home”.

In an interesting essay by Lisa Brice the question of nude

representations of women is discussed. Valadon painted various

self-portraits, including three (1917, 1924, 1931), all of which

show her bare-breasted. Following Brice’s analysis of each painting,

we see Valadon in 1917, when “there is a toughness that can be felt

through the treatment of the subject and the handling of the paint”.

Despite the death of her friend Degas, problems with Utrillo’s

alcoholism, and Utter being wounded during the Great War, the

painting, in Brice’s words, emphasises her “femininity”. By

contrast, the 1924 portrait

“shows a masculine body with shrunken breasts and pronounced

neck muscles”. Valadon is “ready to confront the outrage she knew a

depiction of a naked, aged woman would provoke – after all, the

raison d’etre for the nude in French art was sexuality”.

It’s easy to understand what Brice is protesting against when one

considers what a hostile critic in 1929 said of Valadon’s work: “If

Suzanne Valadon has painted hideous shrews in tones of great

vulgarity, it is because she wants to. That is the most disturbing

thing. Apart from two or three works, the most recent, like the

large bathers which are normal and healthy if not graceful, her

female nude studies are treated as caricatures…..As for her flower

paintings, the charm of their colour, their fragility, is always

spoilt by a detail, a basket or ladder, placed there to look

unpleasant. Does it spring from her poverty or her spite?” (as

quoted by June Rose in

Mistress of Montmartre: A Life of Suzanne Valadon (Richard Cohen

Books, 1998).

A 1927 self-portrait has bright colours, and Valadon’s expression

might indicate a sadness, or discontent that only a painting can

suggest. Contrast it to a photograph of her with Utrillo and Utter,

taken in 1926, where she appears happy enough. And, a few years

later, she has “calmed herself” and “looks ahead with dignified

resignation” in the 1931 self-portrait.

All of which brings me to

Martha Lucy’s assertion that Valadon “defied long-held conventions

for presenting the female body as flawless, sensual, and passive”.

Elderly women had been portrayed on canvas in the past, but rarely,

if ever, in a manner that openly pictured the way in which age

affects the body.

It is the female nude that is heavily featured, though some of

Valadon’s early drawings do involve the young Maurice Utrillo. But

she additionally painted landscapes, still-life canvases, and

portraits. I recall exhibitions in 2001 at the Musée Utrillo-Valadon

in Sannois, and in 2009 at the Pinacothèqhe

in Paris, which featured both Valadon and Utrillo, and

finding her work, which seemed to have a greater variety than his,

much more appealing. It’s difficult now to remember in detail

exactly what was in those exhibitions. Utrillo’s pictures of the

streets of Montmartre admittedly had an attractive quality in terms

of postcards and calendars, and the myth of Montmartre, but Valadon,

in my memory, came across as more-assertive, original, and

colourful.

From a personal point of view I find Valadon’s paintings of more

interest than her drawings, though I accept that it’s necessary to

see both in context. Artists develop over time and operate in

different areas as their ideas formulate. There is, also, the

practical question of earning a living with one’s work, and there’s

no doubt that it was necessary for Valadon to make money. Her

impoverished upbringing had hardened her view of the world. She was

not an idealist with a private income which enabled her to choose

what to do: “in practical terms, her family depended on her income.

She began to exhibit in the Salon d’Automne and the Salon des

Indépendants, and she promoted her work to art dealers”.

She started to achieve some recognition for her work, though this

mostly seems to have occurred post-1918, and it can only be assumed

that the 1914-18 War had interfered with both her activities as an

artist and responses to them. The chronology of exhibitions

featuring Valadon lists nothing between 1914 and 1924, though there

is a critical evaluation of her “Black Venus” which was shown in the

1919 Salon d’Automne.

The 1920s and 1930s saw Valadon earning both critical and financial

success. She could afford to buy property, live comfortably, and

travel, but by 1933 she “suffered from mood swings” and eventually

gave up painting, though her 1936 “Still Life with Herring” and the

1937 “Portrait of Madame Maurice Utrillo (Lucie Valore)” indicate

that it must have been a gradual process. Utrillo had married Valore

in 1935, and it is suggested that Valadon did not get along too well

with her daughter-in-law. The

relationship with Utter had broken down, and in June Rose’s words :

“Utter had become a semi-detached member of the family, coming in

and out as he pleased”. He had a string of mistresses and was not

averse to gossiping about Valadon and her problems to members of the

Parisian art community.

Suzanne Valadon died in 1938. She had been successful in her

lifetime, though she was entering into her fifties when critics

began to notice her and her work sold. To quote June Rose again:

“When she was a beautiful young woman, the art critics had

applauded, somewhat reluctantly, the willpower and independence that

had enabled her to become an artist. But the middle-aged aesthetes

who ruled the Paris art scene in the 1920s found Valadon’s lack of

education and defiance of etiquette distasteful, and the emotional

whirlpool in which she floundered an embarrassment”.

Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel

accompanies an exhibition which was held at the Barnes Foundation in

Philadelphia from September 26, 2021, to January, 9, 2022, and will

transfer to Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen on February 24, 2022

to August 1, 2022. It is effectively a catalogue of the exhibition,

and is well-illustrated. There is a useful bibliography, and a

selection of “Texts on Suzanne Valadon”, one of which is an

entertaining interview with her from 1921, in which she talks

informatively about her years working as a model for various

artists.

|