|

TRACES OF DISPLACEMENT

Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, 7th April 2023 to 7th January

2024

Reviewed by Jim Burns

We live in a world in which displacement, the situation whereby

thousands of people have to leave their home countries and

unwillingly move elsewhere, is increasingly a fact of life. Wars,

droughts, dramatically increasingly sea levels have, and will,

continue to affect what happens as debates develop about how we in

places less challenged by climate change or civil unrest should

react to the presence of strangers in our midst. What adds to the

problem is that, perhaps compared to the past, the numbers involved

are much higher. There are worries about how societies with internal

difficulties, in terms of housing, jobs, medical and other

facilities, can possibly take in large groups whose demands on

resources it may not be possible to fulfil without affecting the

lives of established citizens of a country.

The current exhibition at the Whitworth is not designed to explore

the overall social impact of mass displacement and how it changes a

country like the United Kingdom. Rather, it is an attempt to tell a

“partial, fragmentary and yet compelling set of stories” through

paintings, posters, sculptures, tapestries, and other items.

It’s mostly devoted to examples from the twentieth and

twenty-first centuries, but, in a small section dealing with the

effects of slavery, there is

an intriguing eighteenth century etching of the artist Richard

Cosway and his wife being served by their black servant, Ottobah

Cugoano, a one-time slave from Ghana. His story is a classic account

of how displacement can influence a person’s life and activities.

From the twentieth century the earliest example of mass displacement

is Frank Brangwyn’s 1914 poster illustrating Belgian refugees

fleeing from Antwerp as German troops advanced on the city. Many

Belgians came to Britain around that time, as readers of Agatha

Christie’s Poirot books will know. It’s clearly a form of

propaganda, though executed with skill, and meant to arouse sympathy

for the refugees. Brangwyn also put his talents to use to raise

funds for Spanish refugees at the time of the Spanish Civil War in

the 1930s. Other posters in the display by William King and Ethel

Franklin Betts Bains refer to the work of the American Committee for

Relief in the Near East, and relate to the Armenian tragedy during

the First World War and the plight of Greeks when there were

hostilities between Turkey and Greece.

The 1930s saw many Jews displaced from Germany among them the

artists Lucien Freud and Frank Auerbach, both represented in the

exhibition. They arrived in this country and made major

contributions to the British art scene. They weren’t the only ones.

There is a good case to be constructed for the impressively

beneficial presence of Jewish immigrants in the film, literature and

art worlds of the United Kingdom over the years. Their displacement

worked to our advantage.

With current crises in Ukraine, Sudan, Syria, Afghanistan, and many

more locations the fact of displacement becoming a permanent

situation, with its emphasis shifting from area to area, is a

reality we have to accept and deal with. How artists will come to

terms with their individual circumstances is something that remains

to be seen, though suggestions of it can be found in the exhibition.

As mentioned earlier, the available evidence so far tends to be

“partial” and “fragmentary”. What comes next may surprise us. In the

meantime it’s worth making a visit to the Whitworth to see work by,

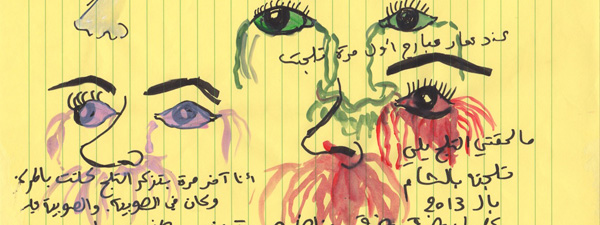

among others, the Palestinian Bashir Makhoul, Lada Nakonechna (her

“Historical Picture of the Contemporary Ruins” is a bleak comment on

what’s happening in Ukraine) and Francesco Simeti. His wallpaper

print, “Arabian Nights”, is colourful and lively.

|