|

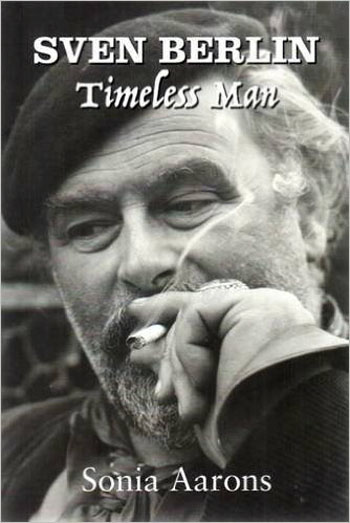

SVEN BERLIN: TIMELESS MAN By Sonia Aarons Millersford Press. 412 pages. £55. ISBN 978-0-9572736-2-7 Reviewed by Jim Burns

It would be interesting to question a few of the people who crowd into the blockbuster exhibitions in London and elsewhere these days and find out what, if anything, they know about Sven Berlin. People are often swayed by names and by being told who they should admire. I doubt that Sven Berlin’s name crops up too often in surveys of what is looked on as important art in the years after the end of the Second World War. And yet he did play a part in the events during a period when, for a time at least, attention focused on what was seen as a group of major artists. What happened in St Ives in the years between 1945 and 1960 has been written about fairly extensively, though often with Berlin relegated to a minor and contentious role. He was born in London in 1911. His mother had some artistic ambitions, though they remained unfulfilled, and he had an aunt who was married to an artist. He showed some talents for drawing and was pushed by his father to become an engineering draughtsman, though he preferred to visit art galleries. He was eventually allowed to enroll at Beckenham Art School in 1928. A career as an artist may have seemed on the cards, but Berlin, a good dancer, met Phyllis Groom and, in due course, they began to tour together as Sven and Helga, their speciality being an adagio act. Touring meant a steady procession of second-rate music halls in drab towns, seedy lodgings, and tiring train journeys. It had to end at some point, and after marrying the pair moved to Cornwall where Berlin could concentrate on painting while making some money with farm work. I’m necessarily moving the account of his activities forward fairly fast, and Sonia Aarons provides a much more detailed narrative. When the Second World War started, Berlin initially registered as a conscientious objector but later changed his mind and joined the Royal Artillery. He saw action in France after D-Day but was eventually invalided out in 1945. He wrote poetry, as well as painting, and a wartime poem, “Hill 312,” published in Modern Reading in 1945, related to his experiences in September, 1944. Prior to going into the army, Berlin had been working on a book about Alfred Wallis, the St Ives “primitive” painter who had attracted the attention of Ben Nicholson. The latter had an almost-proprietorial attitude towards Wallis, and Berlin’s interest in him wasn’t to Nicholson’s liking. It was a dispute that lingered for some time, with Berlin more or less accusing Nicholson of exploiting Wallis by buying his paintings at low prices and selling them for higher ones. It was 1949 before Berlin’s book was published. The war, and the separation it had inevitably caused, led to the break-up of his marriage to Helga. He returned to Cornwall and moved into The Tower, a “concrete store originally used in conjunction with the nearby fishermen’s hut”. He soon formed friendships with the painter Bryan Wynter and the printer Guido Morris. He also met Peter Lanyon, though he, as a native-born Cornishman, seemed to resent Berlin’s interest in Alfred Wallis. There was a St Ives Society of Artists (STISA), to which Berlin initially belonged, but a number of artists, including Berlin, Wynter, Lanyon, and Morris, broke away and formed the Crypt Group. It was around this time that Berlin began to think seriously about becoming a sculptor as well as a painter. He also, in 1946, had a solo exhibition of paintings and drawings at the Lefevre Gallery in London. Berlin was exhibiting, sometimes alongside others from St Ives, sometimes alone, at various locations, including the Downing Bookshop in St Ives, the Leicester Galleries in London, and the Mid-Day Gallery in Manchester. A further split within STISA led to the Penwith Society being established, with Berlin, Barbara Hepworth, John Wells, Peter Lanyon and others as members. There was more dissension between Berlin and Lanyon regarding press coverage of the group’s activities, with Lanyon insisting that all such matters should be handled by him. And even more problems when Berlin’s Alfred Wallis book was published in 1949. He was, by this time, living with Jacque Moran, though another lady, Juanita Fisher, had appeared on the scene, and would eventually leave her husband and move in with Berlin, though she found that she wasn’t completely in tune with his bohemian life-style and drinking habits. By 1950, four rebels, including Berlin, had left the Penwith group over a dispute about the acceptance of work. Sonia Aarons refers to a humorous story, “Abracadabra, or the A.B.C. of Art”, by Nina Masel, published in the Summer. 1950 issue of Denys Val Baker’s magazine, The Cornish Review, which neatly lampooned the disputes among the artists. It’s worth reading if you can find a copy of the magazine. Abstraction was becoming the dominant fashion and Berlin’s adherence to the figurative put him at odds with other artists in St Ives. He made an interesting comment around this time: “Theories on art and the dividing of art into categories I have always left to those better fitted than I – the philosophers and the fools: mainly the fools, I’m afraid….I’m simply concerned with the making of images and with the perfection of my craft according to the processes of their creation. That is all there is to it”. There were problems, too, with regard to Berlin’s home, The Tower, when the local council decided to evict him so that it could be converted into a public lavatory. It was all building up, the personal and what might be termed the political, when he refused to rejoin the Penwith Society. He was warned that by doing so he was “putting himself outside the art establishment and the interests of such organisations as the Tate, the Contemporary Arts Society, the Guggeneim and the Arts Council if he refused”. Berlin being Berlin, he continued to hold out and, in his own words, “set the course of my future for the next thirty years, and even longer……my sentence was exile”. He made the decision to leave St Ives and move to the New Forest and live among the Gypsies in that area, leading an impoverished existence and painting. He wasn’t completely ignored, because the fact of his being among gypsies aroused some interest from journalists. And he did have work exhibited, both locally and in one or two London galleries still interested in what he was doing. But it wasn’t an easy period, though sometimes enlivened by visits from friends and the curious. One such visit brought the famous composer, Ralph Vaughan Williams, to see him in the hope of hearing some traditional gypsy songs. It ended with them all being thrown out of the local pub. There was a Pathe News film which featured Sven and Juanita outside their caravan, and their unconventional lifestyle must have startled some people in what Sonja Aarons refers to as “the dark drab and conservative days of the mid-fifties”. But all was not well with the relationship between Berlin and Juanita. She felt neglected because he spent so much time working, and he suspected her of infidelity with a young groom they’d hired to look after their horses and other animals. Berlin had continued to write as well as paint and sculpt, and his war memoir, I Am Lazarus, was published in 1961 to some acclaim. But his writing was soon to bring problems that would affect him both personally and financially. His satirical novel about St Ives, The Dark Monarch, appeared in 1962 and almost immediately ran into trouble. The characters in the book were clearly based on actual people Berlin had known when he lived in St Ives, and anyone with an awareness of them could easily recognise who they were. The poet Arthur Caddick, for example, clearly provided the basis for Eldred Haddock, a drunk with a drug problem. He, and some others in St Ives, got together and discussed taking legal action for libel against Berlin. None of the artists who could have recognised themselves decided to sue, but Caddick, and two women, went ahead and claimed damages. Caddick, in particular, was notoriously litigious and had previously sued the Canadian writer, Norman Levine, who lived in St Ives, because of a supposed detrimental description in one of his stories. Caddick might also have been keen to settle old scores with Berlin, the pair having tangled in St Ives pubs, with Caddick coming off worse. The story surrounding The Dark Monarch is quite complex, and Aarons tells it in detail. Suffice to say here that it led to the book being withdrawn. The effect on Berlin was damaging, both in terms of his finances (he constantly scuffled to stay solvent) and his psychological condition. He seemed not to have understood how deeply some people in the St Ives community resented his portrayal of the town (called Cuckoo Town in the book) and its residents. One of the people who sued, a doctor’s wife who had been a good friend of Berlin’s, couldn’t understand why she had been portrayed so nastily. Aarons says that Berlin later admitted that the description was “spiteful and unkind.” Likewise with his lampooning of Mabel Lethbridge, a local character who had lost a leg in a First World War munitions factory accident, and was known for her good works among the sick and dying. Berlin might have got away with the references to Eldred Haddock’s drinking (there were plenty of people able to testify to Arthur Caddick’s propensity for alcohol, and he himself happily admitted to it in many of his poems) but the drug-user suggestions went too far. Adding to Berlin’s woes was the fact that Juanita had left him and gone off with the groom, Fergus Casey. A period of depression was soon dispensed with when he attracted the attention of the much younger Julia Lenthall. She was 18 and he was 39, but their romance blossomed and they were eventually married. Berlin continued working and his book, Jonah’s Dream, was published in 1964 and attracted some attention, at least from the angling fraternity. But he was, as Aarons puts it, “still in impossible financial straits.” And she adds that “any money that did find its way into the household largely disappeared in the public houses of Emery Down, Minstead and Lyndhurst”. A sale of a painting or sculpture, or receipt of a cheque from any other source, always led to a celebration. “We partied for ten years!” Julia said. I don’t want to give the impression that the only part of Sven Berlin’s life worth considering is his involvement with St Ives in the late-40s and early-50s, and the later fuss surrounding the publication of The Dark Monarch. Attention will almost inevitably focus on it, but Sonia Aarons is careful to give a full account of what happened after 1964 or so. He carried on painting, sculpting, and writing, and had exhibitions of his work here and there, though sales were often poor. Some old friends rallied around and tried to help, but not with any success. He published poems and articles in the Western Mail, though it’s doubtful that the income from that source would have been very much. He had to sell his home and move to the Isle of Wight. His books Dromengro: Man of the Road (1971) and Pride of the Peacock (1972) got good reviews, but didn’t sell enough to ensure any sort of steady payments. A later book, Amergin: An Enigma of the Forest (1978) simply sank almost without a trace. It was a bohemian life, full of ups and downs, and Berlin wasn’t getting any younger. A revival of interest in St Ives in the 1980s helped draw attention to Berlin, though without necessarily improving his precarious financial position. And when the Tate had its major 1985 exhibition, St Ives 1939-64: Twenty Five Years of Painting, Sculpture and Pottery, only one Berlin sculpture was shown, though a drawing of Guido Morris was included in the catalogue. Aarons records that Berlin claimed not to be too perturbed at “the almost total exclusion” of his work, and remarked, “I was with them but not of them”. The problem may have been that the exhibition largely focused on the abstract painting and sculpture linked to St Ives in the period concerned, and Berlin’s work didn’t, on the whole, fit into that category. Peter Davies, a writer on art in St Ives, was of the opinion that “by challenging the abstract orthodoxy of the day he became a victim of an artistic power struggle”. And the Tate exhibition possibly reflected what the outcome of that struggle had been. The 1990s found Berlin still active. Irving Gose, a gallery owner who supported Berlin’s work, said of him; “No ordinary life his – but an epic on a grand scale with Sven, like a Greek hero, struggling with adversity to achieve his goal”, and Toni Carter, Editor of the St Ives Times & Echo, reckoned that: “Only when all of Sven’s works are considered as one `great work’ can this `giant’s’ contribution to art be realised”. But the continued hostility of the art establishment was probably summed by John Russell Taylor, The Times art critic, when he referred to Berlin as “a curiously anachronistic figure; a sort of displaced Edwardian, with his slightly fustian style and reach-me-down mysticism”. What was perhaps Berlin’s most-engaging book, the autobiography, The Coat of Many Colours was published in 1994, and a second volume of autobiography, Virgo in Exile, appeared in 1996. When Patrick Heron, artist and theorist for modern abstract British art, died in 1999, Berlin told a friend: “as the patterns changed and reformed he distanced himself from me……..he was probably the one who got me excluded from the higher echelons because of my outspoken views & refusal to stand on my tail or correct my behaviour in other ways…..He was a sensitive, friendly man, obviously gifted, but with a deceitfulness which left you in no doubt about his method of promoting himself before others”. Sven Berlin died in 1999. How good was he as an artist? He produced a great deal of work – paintings, drawings, sculpture, poetry, a variety of books – some of which was good, some not so good. I remember, when I saw the exhibition, Sven Berlin: Out of the Shadows at the Penlee Gallery in Penzance in 2012, thinking that it was almost impossible to separate the life and the work. Berlin’s paintings often reflected his personality, and both were colourful. Arthur Caddick perhaps had a point when he said that Berlin “had created one masterpiece that was permanently on show. It was himself.” And the exhibition did seem to have a large number of self-portraits. Caddick also thought that Berlin was “every girl’s dream of what an artist should look like.” Bearing in mind how Caddick reacted to being portrayed as Eldred Haddock in The Dark Monarch, it could be that he was trying to hit back with his comments. But Berlin does seem to have been often deeply self-centred, and he courted publicity when he could. In some ways, though I’m not talking about their painting techniques, Berlin reminds me of John Bratby, another colourful misfit on the British art scene who still isn’t given the acknowledgement he deserves. Bratby was prolific as a painter, and also produced novels, short-stories, and other writings. An exhibition I saw of his work in Hastings earlier this year convinced me that he could be very good at times, but also quite indifferent at others. And, again like Berlin, the fact that he turned his hand to a variety of involvements, like painting, drawing, writing, made the art establishment suspicious of him. The English just don’t have a taste for bohemianism, flamboyancy, and versatility. Someone commenting on Bratby after his death said that he didn’t fit in because the English “expect their painters to use subdued colours, create works laboriously, and to be taciturn”. If that is the case then it’s no wonder that Sven Berlin was frowned on by the art establishment. Sonia Aarons has written a richly detailed life of Sven Berlin which is also informative about events in St Ives when he was living there. He would never allow The Dark Monarch to be reprinted while he was alive, but a new edition, complete with a guide to the characters and their real-live counterparts, was published in 2009. But it shouldn’t be thought that the St Ives story dominates the biography, even if it was a significant period in Berlin’s life. It doesn’t and we learn a great deal about how Berlin coped with the vicissitudes of life as an artist generally. There are numerous illustrations and a small, but useful bibliography.

|