|

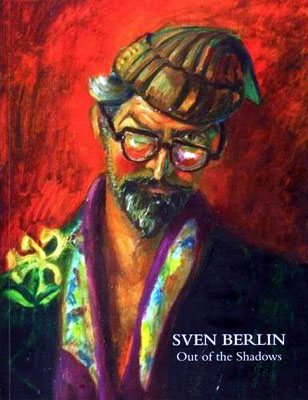

SVEN BERLIN: OUT OF THE SHADOWS An exhibition at Penlee House Gallery & Museum, Penzance, 15th September to 24th November, 2012. SVEN BERLIN: OUT OF THE SHADOWS by Sonia Aarons with contributions from David Wilkinson and John Paddy Brown. Published by Millersford Press. 108 pages. £22.50. ISBN 978-0-9572736-1-0 Reviewed by Jim Burns

The saying, "They don't make them like that anymore," is often used loosely and without any evidence to show that the person referred to had any real claim to being special or different. But in Sven Berlin's case it rings true. He had led a genuinely varied and colourful life, so much so that he may not have been seen as the serious artist that he was. Someone viewing Berlin and his work in a casual way could easily dismiss him as typifying the common idea of how a bohemian looks and lives. He deserves better than that. He was born in 1911 in London into a middle-class family with Jewish and Swedish roots. His childhood appears to have been happy, though he had problems when he was sent to boarding school and was bullied. However, an art mistress introduced him to watercolours and so helped him develop a taste for art. He was expected to go to university, but the family business failed and his life took a different turn. He went to stay with an aunt who knew John Masefield and Augustus John and told him tales of associating with gypsies and the bohemian life. He read widely and frequented Dulwich Gallery and similar places. His desire to break away from bourgeois existence, with its threat of having to take a mundane job, was fulfilled when a friend of his sister needed a dancing partner. By 1933, Sven and Phyllis Groom were touring as Sven and Helga, specialising in adagio dancing. Posters and other ephemera in the exhibition (and its accompanying book) show that they appeared in theatres in Liverpool, Portsmouth, and elsewhere, perhaps never topping the bill but working alongside popular performers of the day. Berlin was determined to make his mark as an artist and continued to draw and paint. There are some delightful caricatures of now-forgotten fellow-troupers like Nellie Wallace and Wakefield, O'Neill and Nelson. And a striking poster that he designed to publicise his partnership with Phyllis Groom. Berlin had little formal art training but seemed to have a natural talent for sketching and an eye for bright colours, if another poster showing flamenco dancers is anything to go by. It's interesting to note that, much later, Berlin drew a parallel between dancing and sculpting: "Dancing is also the human form and the poetic image in space seen and inwardly experienced from many viewpoints in time, developed on the laws of gravity, rhythm, colour tension, the spiral and the arabesque.....Carving is a dance over and under and round and through a piece of stone during the creation of a three-dimensional image in space, which is worked out in a series of kinetic relationships of form that force the observer to move..... Although my work on stage was a kind of bastard dance, I worked hard and with enough devotion over eight years to make me realise that to dance was to know the stress and strain of a steel constructed bridge, the law of moving water, and the behaviour of heavenly bodies." When those comments were published in The Cornish Review in 1949 (and I've extracted them from a longer piece) they drew a response from Peter Lanyon who referred to Berlin's "blatant conceit," and his "woolly philosophy and technical absurdities, his disregard for historical and traditional methods of carving." Lanyon and Berlin had been founder members of the Crypt Group in 1946, but it was obvious that their relationship wasn't all sweetness and light. Sven and Helga (who he married in 1937) had eventually tired of touring the halls and had decided to move to Cornwall, where Berlin found work as a labourer on local farms and studied in the evenings at the Redruth and Camborne Art School. When war was declared in 1939 he registered as a conscientious objector, though by 1942 he had changed his mind and joined the army. He continued to work at his art and sketched scenes of military life as the troops trained and waited for the forthcoming invasion of Europe. When it took place Berlin landed in France shortly after D-Day. His experiences, which he wrote about in I am Lazarus, published in 1961, affected him badly and he was invalided out of the army suffering from shell-shock and jaundice. It's relevant at this point to mention Berlin's interest in Alfred Wallis, the St Ives primitive painter who had been taken up by some of the artistic community, and especially by Ben Nicholson. Berlin gathered information about Wallis for a projected book (it was published in 1949) but Nicholson, who had an almost-proprietorial attitude towards Wallis, was reportedly not happy about someone else, particularly a newcomer like Berlin, moving in on his territory. It's always difficult to know the real reasons why artists, writers, and other artistic people, fall out, but it's possible that the seeds of further disagreements between Berlin and Nicholson were being sown when they differed about Wallis. It was in the post-war period that Berlin became, for a time at least, a key figure in St Ives. He was friendly with the Canadian writer Norman Levine, the poet W.S. Graham, the printer Guido Morris, and the painters Bryan Wynter and John Wells. The 1945-60 period in the history of art in St Ives has been written about in detail in articles and books (see Michael Bird's The St Ives Artists, for example) and a summary of activities and events can be found in Sylvia Aarons' book. There were tensions as well as friendships and a split in the St Ives Society of Artists which led to the formation of the Penwith Society of Artists in Cornwall, though even this group had arguments about who to admit to membership and the kind of art that would be seen as acceptable. Ben Nicholson's inclinations were towards pure abstract art, whereas Berlin favoured a more-representational sculpture and painting. His sculpture, "Mermaid and Angel," was rejected by the Penwith Society in 1948 because it wasn't abstract. The decision by Berlin to withdraw from the Penwith Society probably led to his being ostracised by some members of the St Ives community. And almost certainly to his being overlooked by buyers and critics who were increasingly drawn to St Ives as a centre for major modern art. Ten or so years later he satirised many of the personalities involved in his novel, The Dark Monarch. The controversy surrounding the publication of The Dark Monarch brought Berlin to the point of bankruptcy. The fictional characters were based on real-life ones and were recognisable by anyone with an awareness of St Ives and its inhabitants. The poet, Arthur Caddick, who had been a friend at one time, took exception to being portrayed as Eldred Haddock, a drug-addicted writer. He played a leading role in persuading several other people to 'take legal action to get the book withdrawn from circulation. It's a fact that the four people concerned weren't artists. Caddick had some standing as a minor poet, but the others were only linked to the arts by association. The Dark Monarch was withdrawn, partly because Berlin refused to make any alterations to the text, and was only published again in 2009. Why Berlin chose to write The Dark Monarch years after he'd left St Ives in 1953 remains a mystery, though he did claim that his purpose was "to entertain" and to "interpret experience." It's possible that the events of the late-1940s and early-1950s in St Ives had, like his war experiences, left scars. He and his second wife (his marriage to Helga had foundered during the war) moved to the New Forest where they became friendly with and were helped by the local gypsies. Later, after the row about The Dark Monarch, they went to the Isle of Wight. Berlin had shows here and there, got a few commissions, wrote, and painted and sculpted. Among his books was The Coat of Many Colours which looked at the years spent in St Ives. But I think it's fair to say that he was something of a forgotten figure. It's perhaps significant that in 1984, when the Tate in London mounted a major exhibition, St Ives 1939-1964, he was represented by only one sculpture and none of his drawings and paintings were included. It was almost a token acknowledgement of his presence in St Ives during several of the years concerned. I suppose flamboyancy had always been a Berlin characteristic and he did tend to look like a bohemian, or at least what people think a bohemian should look like. The years living in caravans in the New Forest made for good copy for journalists, as did the fact that his third wife was thirty years younger than him. Chris Stephens, in his forward to the book, quotes Arthur Caddick as saying that Berlin "had created one masterpiece that was permanently on show. It was himself. He was every girl's dream of what an artist should look like." And going around the exhibition a viewer might begin to wonder about the number of self-portraits on display. Plenty of artists paint self-portraits, but Berlin almost carried it to extremes. Caddick's comment was no doubt meant sarcastically, and Berlin had, on one occasion, knocked Caddick down after an argument in the Castle Inn, but he may have had a point. It's interesting, incidentally, to look at Berlin's 1951 pen and ink portrait of Caddick which isn't exactly flattering. I've dealt with Berlin's life in some detail because it seems to me that the life and the art can hardly be separated. The paintings often reflected his personality. Walking into the gallery I was immediately struck by the vitality and colour of the works on display. Sometimes appearing almost rough in execution they leap out from the walls. The 1956 "Fruits and Flowers," with its reds and greens and other colours, makes one want to handle the fruit. "Celebration," which is, in some ways, almost another self-portrait, though it largely focuses on his young wife, has a cheerful and almost cheeky air to it that engages the viewer. Berlin caught the moment - his delight at his life being rejuvenated - and it has lasted on canvas. The dominant dark green tint of "Ernie Veal by Moonlight" suggests a great deal about the nature of the man - an amiable rogue. As for the sculpture on display, it surely has links to an earlier era and it's easy to understand why it didn't fit in with the cool abstractions of Barbara Hepworth. Berlin was much more passionate, an "obsolete romantic," as someone described him. I would draw attention to his "Albatross in Flight," carved out of marble and totally effective in its simplicity. He seemed to have a knack for both sculpting and drawing or painting animals, and birds. Something that occurred to me when looking at the sketches and paintings of gypsies was that it could be that Berlin didn't feel a sense of competitiveness when he was in their company. St Ives, in contrast, must have been a hotbed of competing egos. With the gypsies he could probably relax more and enjoy their company. It comes through in his work and he could exploit his liking for vivid colours even if, in reality, life in the compound at Shave Green was "hard and drab." Perhaps what he was expressing through colour was the resilience of the people in the face of adversity. This is an excellent exhibition and will hopefully draw attention to an artist who, if not a major figure, was often very good. There is some fascinating background material in the form of posters, books, photos, letters, magazines, and much more that provides a picture of his talents. Dancer, soldier, sculptor, painter, novelist, poet, biographer (of Alfred Wallis), autobiographer. He didn't easily fit into the conventional English art scene. They really don't make them like that anymore.

|