|

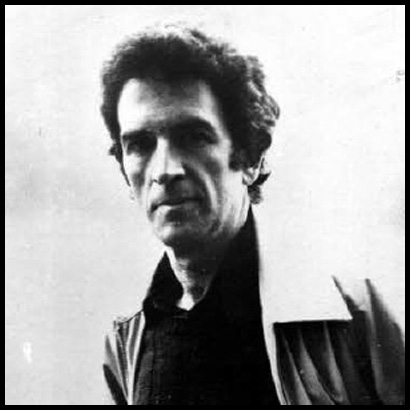

CLANCY SIGAL

(1926-2017)

by Jim Burns

Clancy Sigal wrote a book called

Going Away: A Report, a

Memoir that was marketed as a novel, but which was essentially

an autobiographical account of how and why he left the United States

in the late-1950s. It wasnít his first published book.

Weekend in Dinlock, which appeared in 1960, preceded it, and

pointed to the fact that Sigal was by that time living in Britain.

Weekend in Dinlock

was interesting in that it was about the friendship between an

American radical and a young British miner who was also a talented

artist. It was, in fact, based on Sigalís association with Len

Doherty, a miner from the North East who was also a novelist. Itís a

sad question to raise, but does anyone read Doherty these days? He

published three novels, became a journalist, and died in 1983.

Weekend in Dinlock was

widely read, but didnít always impress those on the political left

in Britain.

It didnít paint a picture of working-class life in a pit village as

being anything other than it was, with heavy drinking and

narrow-mindedness being integral parts of it.

Sigal had been introduced to Doherty by Doris Lessing, and they had

in common their membership of the Communist Party in their

respective countries. And it was the communist connection that had

pushed Sigal into deciding that departing from American was, in the

circumstances of the Cold War and anti-communist feeling, a wise

move. He naturally gravitated towards left-wing circles in

London, and for several years had an affair

with Doris Lessing. He appears, in fictional form as Saul Green, in

her novel, The Golden

Notebook. She, in turn, is portrayed as Rose OíMalley in Sigalís

novel, The Secret Defector.

Sigalís left-wing inclinations were shaped by his parents. His

father, described as ďa gun-toting labour organiserĒ, came and went

in an irregular way, and he was brought up by his mother, who also

happened to be heavily involved in left-wing politics and union

organising. His book, A Woman

of Uncertain Character: The Amorous and Radical Adventures of My

Mother Jennie (Who always Wanted to be a Respectable Jewish Mom) by

Her Bastard Son is a racy account of what it was like growing up

in Chicago in the 1930s and 1940s with parents, and their friends

and acquaintances, often engaged in factional fights with other

left-wingers: ďThere is hardly a Jewish clan of their generation

that was not bitterly split between the Ďistsí Ė socialists versus

Communists or both against the Trotskyists who didnít like the de

Leonists who loathed the Cannonites who despised the Shachtmanites

who Ė and on and onĒ. Itís an amusing aside to Sigalís early years

that he said that the first time heíd been in prison was when he was

five years old. His mother had been arrested for her union

organising activities, and she took her son to prison with her.

After army service, Sigal returned to Chicago and attempted to find a place for

himself as a union organiser for the United Automobile Workers

(UAW), but the union was starting to purge communists and their

supporters from its ranks. Sigal moved to the West Coast, but

continued with his radical activities. He once claimed that he had

been fired from Columbia Studios when he was found using their

copying facilities to run off political leaflets.

Much later, when he was living in London, Sigal had other involvements, perhaps

not political in the usual sense, but certainly considered radical

at the time. Always good at turning his experiences into

lightly-disguised fiction, Sigalís

Zone of the Interior had

its basis in his relationship with the controversial

anti-psychiatrist, R.D. Laing. What was noticeable about Sigal was

the fact that he always managed to deal with a subject with an

element of humour built into the narrative. It was as if he was

looking at himself and wondering how he had become involved in

whichever situation he was in. The humour was, perhaps, a kind of

survival technique.

But itís probably for Going

Away: A Report, a Memoir that Sigal will be most remembered. In

it the narrator leaves the West Coast where he had been active, in

various ways, in the film industry, and drives across the United States. On the way he visits

old friends and finds them inevitably altered. The McCarthy years

have had their effect and one-time union and political activists are

keeping their heads down. Theyíre often family men now, and need to

hold onto their jobs. The American Left has effectively fallen

apart. Alongside the encounters with old and new friends there are

loving descriptions of the landscapes, both

urban rural, that are observed. Some commentators have almost linked

Sigalís book to Jack Kerouacís

On the Road, but with

Sigal showing a greater social and political awareness.

I donít think Sigal meant to stay away from America as long as he did Ė his original

intention was to spend six months in

Paris, writing

Going Away : he did and

inevitably got to know Simone de Beauvoir and other intellectuals

and political activists

Ė but it was thirty years before he made a permanent move back to

his homeland. In those thirty years heíd written his various books,

worked for the BBC, and The

Guardian, The Observer,

Encounter, and other publications, and generally built up a

reputation as a lively and sometimes combative journalist. A book

about his adventures in England is

scheduled to be published in 2018.

When he did return to America,

he lived in California, got

married, taught at the

University of

Southern California, and

was once again involved with films, sometimes as a screenwriter.

He was the principal screenwriter for the film,

Frida, about the life of

the Mexican artist, Frida Kahlo. The final book published during his

lifetime was Black Sunset:

Hollywood Sex, Lies, Glamour, Betrayal and Raging Egos, a

fast-moving account of his sometimes bizarre experiences working as

a talent agent in Hollywood

in the 1950s.

I always read anything that Clancy Sigal wrote whenever I came

across it in book form or in the pages of newspapers and magazines.

He was never dull. And he could always tell a good story. He was

spoken of as being in a class with other Chicago-related writers

like James T. Farrell and Nelson Algren. There are much worse ways

to be remembered.

|