|

ROSS RUSSELL AND BEBOP

By Jim Burns

I recently re-read Ross Russell’s novel,

The Sound, certainly not

for the first time and probably not for the last.

It’s not a literary classic, but the subject-matter and

Russell’s vibrant accounts of the characters and the milieu in which

they operate always fascinates me. His descriptions of the music at

the centre of the book make me want to get out the records from the

period and listen to them again.

It’s not surprising that Russell describes the music so well. He had

played an important role in the early days of the bebop movement of

the 1940s, not as a musician but as someone who helped draw

attention to bop by starting a company to record Charlie Parker and

other practitioners of the new sounds. Not many major record labels

were interested in promoting bebop in the mid-1940s and it was left

to Dial, Savoy, and other scattered small companies to take a chance

with artists like Parker, Dexter Gordon, and Howard McGhee. There

are stories about some of the small record labels that came and went

in the 1940s, and their shady ways of operating, but without them

there would have been fewer examples available of the changes taking

place in jazz and popular music.

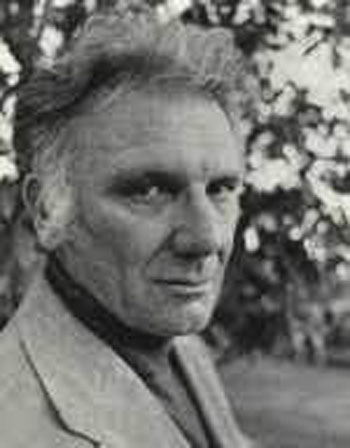

So who was Ross Russell? He was born in Los Angeles in 1909. In the

1930s he published pulp fiction in magazines, and was a great

admirer of the work of Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler. He

served in the Merchant Marine during the Second World War In both

the European and Pacific theatres. When the war ended he returned to

Los Angeles and, being an enthusiastic jazz fan, decided to open a

record shop. He was initially a collector of traditional-style jazz,

but when he started to listen to the records by Charlie Parker that

local hipsters ordered he became interested in bebop. Opening a

record shop was probably a wise choice in more ways than one.

Russell had considered trying to get into screenwriting in

Hollywood, but later reminisced that, had he done so, he might have

been caught up in the HUAC investigations into communism in the film

industry. Most of his contacts in the studios were writers who were

later blacklisted.

His next step was to form a record company, Dial, to record Charlie

Parker who he had met and become friendly with. Parker was in Los

Angeles with a group led by Dizzy Gillespie which had a booking at

Billy Berg’s Club in Hollywood. But he was proving to be somewhat

unreliable due to his drug addiction and the fact that narcotics

were not as easy to come by on the West Coast as they were in New

York. Parker asked Russell to be his manager, and he also willingly

signed an agreement to record for Dial. He was actually under

contract to another company at the time.

I’m not intending to analyse the music that Parker produced for

Dial. There were seven sessions, some recorded in Los Angeles, some

in New York after Russell had moved there. Russell’s own accounts –

there were several – can be found in various places, the most

accessible probably being in

Bird: The Legend of Charlie Parker, edited by Bob Reisner. But

one recording date does stand out, if not for the best reasons. In

July, 1946, Parker went into the studio and came up with the music

from the famous (or infamous)

Lover Man session. He was in poor condition, due to being unable

to obtain the necessary supply of heroin, and was barely able to

play. Howard McGhee, the trumpet player on the date, was a tower of

strength, but even he, and the rhythm-section, could not cover up

for Bird’s dismal performance.

It has always been a matter of contention whether or not the four

tracks that Parker managed to stumble through should have ever been

released. But they were, much to his annoyance. Russell’s

intentions, beyond wanting to try to recover his losses, can be

questioned, and they led to accusations of exploitation. Had he

realised that there would be an audience for recorded evidence of a

great jazzman breaking down? In the studio was a journalist

associate of Russell’s, a man called Elliot Grennard who wrote a

short-story called “Sparrow’s Last Jump” which was a

lightly-fictionalised account of the events of that day. It was

published in Harper’s

Magazine in 1947. He later recalled Russell saying that he’d

“lost a thousand bucks” because of what had happened. At the end of

the story the narrator makes the comment: “Yeah, Sparrow’s last

recording would sure make a collector’s item. One buck, plus tax, is

cheap enough for a record of a guy going nuts”.

Russell had recorded other modern jazz musicians in California –

Dexter Gordon, Wardell Gray, Dodo Marmarosa, - and besides making

the final Parker records for Dial in New York in 1947, he produced a

session with singer Earl Coleman backed by the brilliant trumpeter

Fats Navarro and tenor saxophonist Don Lanphere. There may be an

irony in the fact that Russell seemed keen to record Coleman. In

1947 when Parker brought the singer to a Dial session and insisted

he should be recorded, Russell had remarked that he needed a singer

like he needed a hole in his head. Bird’s version of “This is

Always”, with a vocal by Coleman, turned out to be one of Dial’s

best-selling discs.

After 1948 Russell seems to have given up on jazz, at least from a

recording point of view, and focused on contemporary classical

scores, releasing records of the music of Schoenberg, Ernst Krenek,

and others. In the 1950s he turned to documenting calypso music in

the West Indies. I can’t offer any critical comments on what he

recorded, either classical or calypso, but it has been suggested

that he offended Schoenberg in the same way that he’d upset Parker

by issuing records of what the composer considered sub-standard

performances.

Biographical information regarding what Russell did in the 1950s and

after is fairly limited. At one time or another he lived in various

countries, contributed articles to jazz magazines, taught jazz

history courses at the University of California and elsewhere, and

sold the Dial records catalogue, especially the Parker sides, to one

or two different companies. The material was perhaps best preserved

by Spotlite Records, based in the United Kingdom. Russell had kept

most of the recorded tracks, including incomplete takes, so critics

and ardent fans could study Parker’s work in particular. He claimed

that Parker was often at his best on the first take, even if the

group as a whole didn’t function as well as it did on later takes,

so there was a good reason for issuing everything that survived. It

was Parker’s music that mattered most of all.

Russell also wrote several books, beginning with

The Sound, a novel based

in part on Parker’s life and music. Published in 1961 it was

generally well-received, in jazz circles at least, though some

people did find the close attention paid to the drugs situation a

little distracting. But

somewhere (I can’t pin down the source) I recall the writer Nat

Hentoff saying of the 1940s: “That’s the way it was, and only

someone looking for serialisation in

Reader’s Digest would

want to pretend otherwise”.

The Sound

is colourful and it’s possible to see Russell’s grounding in the

pulp fiction of the 1930s at work in some of the writing. But

there’s no doubt that he knew the scene in terms of capturing the

nature of the music. Early in the story Red Travers, a

trumpet-player who is closely modelled on Charlie Parker, arrives in

Los Angeles for a club engagement. He’s accompanied by a saxophonist

from New York, but the rhythm-section is comprised of local

musicians, among them Bernie, a white pianist. He isn’t too familiar

with bebop, but has the musical training to follow what Travers is

doing harmonically. His induction into the hot house atmosphere as

Travers launches into a fast first number that initially confounds

everyone apart from the saxophonist, is excitingly evoked by

Russell. It always makes me want to listen to some authentic bebop

whenever I read it. Which is, I think, a tribute to the quality of

his writing when he’s concerned to describe what is happening during

a performance by Travers.

A second book by Russell gave an indication of his genuine knowledge

and appreciation of jazz developments.

Jazz Style in Kansas City and

the Southwest, published in 1971, was a close look at an area

which, as the book claimed, “was the source for many of the musical

ideas that have dominated jazz from the late thirties to the present

and resulted in the bebop revolution and the foundation of modern

jazz style”. Tracing the music from its roots in “the blues, brass

bands, and ragtime” Russell brings it to the 1930s when bands like

those led by Andy Kirk, Count Basie and Jay McShann featured key

soloists, including Howard McGhee, Lester Young, and Charlie Parker.

What is particularly valuable about Russell’s history is that it

doesn’t only document the activities and achievements of a few of

the better-known names. Minor but interesting musicians like Buddy

Anderson and John Jackson are given attention. Anderson, a trumpet

player, “was the most advanced musician in the band (Jay McShann’s)

after Parker”, and Jackson was an alto-saxophonist who, initially at

least, sounded a little like Bird when both were working with

McShann.

Russell’s best-known book was

Bird Lives! The High Life and Hard Times of Charlie ‘Yardbird’

Parker, published in 1972.

Because of his

involvements with Parker, and his experience of the Los Angeles jazz

scene of the mid-1940s, Russell could obviously provide insights

into the events relating to certain of Bird’s activities. This

particularly applied to information about the Dial recordings and

the situations surrounding them. And his awareness of the lively

scene in “Lotus Land”, with its cast of hipsters, oddball

characters, and enthusiastic musicians, added variety to his

account. But questions were raised about some of the events and

facts that Russell wrote about. He had talked to a great many

musicians and others over the years, and it may have been that some

of the information he gathered was more anecdotal than factual, and

therefore not totally accurate. But it still occurs to me to think

that there are things to be gained from Russell’s Bird biography. He

makes the music come alive in a way that later commentators on

Parker, while academically correct, often failed to do.

Russell died in January, 2000. He had been working on a book about

bebop with Red Rodney, but it was incomplete at the time of his

death. He knew the worth of his collection of records, books,

magazines, manuscripts, interviews, and much more, and in 1980 had

sold his archives to the University of Texas. I think he was aware

that his association with Parker and other bop musicians at a time

when major musical developments were in process gave him a place in

jazz history.

NOTES

1. The Sound by Ross

Russell. Dutton, New York, 1961.

2.

Jazz Style in Kansas City and

the South West by Ross Russell. University of California Press,

Berkeley, 1971.

3. Bird Lives! The High Life

and Hard Times of Charlie ‘Yardbird’ Parker by Ross Russell.

Quartet Books, London, 1973.

4. Bird: The Legend of

Charlie Parker edited by Robert Reisner. Citadel Press, New

York, 1962.

5. The Bebop Revolution in

Words and Music edited by Dave Oliphant,

Harry Ransome Humanities Research Centre, the University of

Texas at Austin, 1994. This assembles some of the papers delivered

at a symposium in 1992 and includes a particularly useful piece by

Edward Komara on “The Dial Recordings of Charlie Parker”. There is

also a Keynote Address by Ross Russell which was delivered on his

behalf when health problems prevented him from attending the

symposium. It’s informative about, among other things, the social

and cultural scene in Los Angeles in the 1940s.

6. “Sparrow’s Last Jump” by Elliott Grennard in

Jam Session edited by

Ralph J. Gleason. Peter Davies, London, 1958.

7. Central Avenue Sounds:

Jazz in Los Angeles edited by Clora Bryant & others. University

of California Press, Berkeley, 1998.

8. Jazz

West Coast: The Los Angeles

Jazz Scene of the 1950s

by Robert Gordon. Quartet Books, London, 1986. Despite its title

the book has a couple of useful chapters about jazz in Los Angeles

in the 1940s

9. West Coast Jazz: Modern

Jazz in California 1945-1960 by Ted Gioia. University of

California Press, Berkeley, 1998.

10. Bebop: A Social and

Musical History by Scott DeVeaux. University of California

Press, Berkeley, 1997.

Readers may be interested in my essay, “Bird Breaks Down” in

Beat Scene 49, Coventry,

Winter 2005/6, and in

Radicals, Beats and Beboppers, Penniless Press, Warrington,

2011.

|