PULP FICTION

Jim Burns

Pulp fiction. It’s a term usually designed to dismiss what is being referred

to as not worthy of serious consideration. It’s said to be literature

designed for quick and easy reading and hardly taxing the intelligence of

the reader. That’s certainly how it is often seen, and there is, perhaps,

some truth in how its limitations are defined, at least on a general level.

But, being of the opinion that good writing is where you find it, I’ve more

than once been pleasantly surprised to come across it in a pulp novel I’ve

read. I’d agree that it’s necessary to pick and choose carefully when

delving into the world of pulp. My own liking is for older novels, those

dating mostly from the 1930s through to the early-1960s. After that, it

seems to me, the breakdown in censorship meant that writers were more at

liberty to focus openly on sex and violence, with the result that it was no

longer necessary to suggest it. The imagination declines in such

circumstances.

This is a contentious issue, and I’m not advocating censorship, simply

pointing to what might have happened when it was relaxed. Writers of pulp

fiction will no doubt disagree with me and claim that they now have greater

freedom to develop characters and situations. But they could surely do that

by suggestion when working within a restricted framework. The fact is that

sex and violence sell books, and pressure is exerted on writers by agents

and publishers to add doses of each to their novels. A crime novelist of my

acquaintance once told me that this was the case.

I don’t want to spend time generalising about pulp fiction. The above

reflections were triggered by the recent discovery of an example of a pulp

book. It’s an interesting item to look at for more reasons than one.

Published in 1962 by Lancer Books, New York, it has two novels –

Season of Love by Colin Ross and

The Wrong Turn by Daniel Harper –

both of them short (123 and 127 pages, respectively) which might suggest

they were written to a specified format. With very few exceptions pulp

novels rarely exceeded more than 250 paperback pages, and many hovered

around the 180 to 220 pages mark. Putting the Ross and Harper books together

(250 pages in total) made sense in that context.

There are one or two curious aspects surrounding when the two novels (do

they fit easier into the novella category?) were written. As mentioned

earlier, Lancer published the book in 1962 and the Ross novel was

copyrighted by them in the same year. But the Harper was copyrighted in that

name in 1954, and a check shows that it was originally published that same

year by Avon Books, New York. The earlier edition isn’t mentioned by Lancer.

I’m making no claims for these books as more than what they are, lightweight

“entertainments” that have inevitably been long-forgotten other than by a

scattering of dedicated pulp readers. There are enthusiasts who specialise

in collecting old paperbacks, often as much for their covers as for their

contents. And there are magazines and books devoted to pulp writers and

their publishers. Some contemporary publishers – Stark House and Hard Case

Crime, for example – find what they think can be usefully salvaged from

bygone years and re-publish it. It all seems to me a worthwhile enterprise,

but I’m prejudiced and freely admit to a long-standing interest in pulp

novels and the stories surrounding them.

To return to the novels in question.

Colin Ross’s Season of Love has

little to recommend it in terms of its capacity to keep the reader attentive

to the storytelling. A young woman with aspirations to be a writer is

involved in a relationship with an older man. She ends it and heads for

Paris where, she thinks, she’ll have the time and stimulus to produce

something creative. In fact, she encounters a series of men on board the

ship, when she’s in Paris, and in the South of France, who all find her

desirable and want to sleep with her. Bearing in mind what I said earlier

about what could appear in print prior to the 1960s the sex scenes are brief

and with little detail. A somewhat contrived ending appears to suggest that

the woman will marry and settle down, although she has made it a condition

of marriage that she be allowed time to write a novel. The book had

previously been published under the title,

The Mistress, by Beacon Books in

1958, but no mention was made of this in the 1962 Lancer publication.

References to young Americans in Paris living on G.I. Grants earned because

of their military service in the Second World War, sets the period as around

the late-1940s and early-1950s. There are also the obligatory inclusions of

Hemingway, the Select, Kiki of

Montparnasse, the Existentialists

and other elements of “local colour” to provide some authenticity. It tends

to come across as designed to appeal to American “stay-at-homes” who can

fantasise about a Paris they may never get to. The writing is functional at

best, pedestrian at worst.

Daniel Harper’s The Wrong Turn is

better written and much livelier. A judge’s wife, Adele, with an older

husband, craves excitement and decides to look for it with a young criminal,

Eddie, she encounters when visiting the judge at his courtroom. She’s bored

with the kind of life she’s leading among the well-to-do social set she‘s

required to associate with in Washington, and the young man has the

potential of offering something different. Her meetings with him are

clandestine at first, but she soon becomes indifferent to the possibility of

discovery. She smokes marijuana, buys clothes more in keeping with the kind

of women he normally associates with, and visits bars and other

establishments where criminals congregate. She doesn’t go unnoticed and a

local gossip columnist makes an oblique reference to her one day.

She’s soon persuaded to participate in actual criminal activities, including

a raid on a Western Union Office during which someone is shot. Eddie drops

the gun while escaping with the money, and

persuades Adele to blackmail her husband into removing Eddie’s

fingerprints from police records. He does so, but realising that what he’s

done will soon come to light he commits suicide, but not before writing a

confession of his guilt. Adele and Eddie panic and drive out of the city but

the car crashes and both are killed. It all sounds very much in the spirit

of the kind of Hollywood productions of the 1940s that were labelled film

noir. There’s the same dark feeling that the relationship between Adele and

Eddie is sure to end as it does. The writing is much more compelling than in

the Ross novel, and pushes the narrative from page to page,

What intrigues me about both books, despite whatever drawbacks they have

when it comes to their literary qualities, is that they were published under

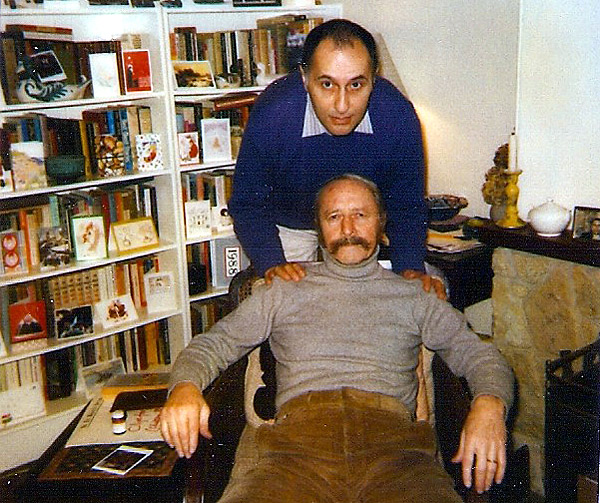

pseudonyms. Colin Ross was Harry Roskolenko, and Daniel Harper was Chandler

Brossard. They were writers with novels and other publications in print

under their real names, and it can only be assumed that the pulp material

they produced was done for the purpose of making a little money,

They were far from alone in doing this, though some writers were happy to

have their real names on the covers of their pulp paperbacks. The

experimental novelist David Markson wrote three pulps between 1959 and 1961.

One of them, Epitaph for a Dead Beat,

used the Greenwich Village bohemian scene that he knew well as a

location for its story. The critic Seymour Krim called Markson’s

Springer’s Progress (not a pulp),

“The most honest and stunning Greenwich Village novel of my time”.

And there was R.V. Cassill, an academic, editor, noted short-story writer,

and novelist who wrote at least nine pulp novels, with titles like

A Taste of Sin and

Left Bank of Desire, as well as

several more published in hardback by major companies. I’m tempted to say

that, on the whole, I always preferred his pulp novels to most of the

others. But what may be his major achievement,

Clem Anderson, is well worth

looking at. A fellow novelist and fine short-story writer, Richard Yates,

said that it was “the best novel I know of on the subject of writing, or on

the condition of being a writer”.

Harry Roskolenko appears to have used a bewildering number of pseudonyms

during his writing career, and I assume that most of them applied to

material that he wrote purely for financial reasons. To take one example

when he again called himself Colin Ross,

New York After Dark was published

by McFadden Books in 1966. It claimed to give the lowdown on the city’s

sleazy side, with chapters on sex orgies, drugs, prostitution (male and

female), lesbians, homosexuals and anything else guaranteed to convince

provincials that New York really was as decadent as they thought.

One chapter inevitably focused on Greenwich Village and at least

demonstrated that the writer had a familiarity with its history as a

bohemian outpost, and with some of its legendary characters like Maxwell

Bodenheim, Eli Siegel, Harry Kemp, and John Rose Gildea. He says that he

“first saw the Village, before World War One”, and seems to have kept up an

acquaintance with it over the years. He waxes nostalgic for older periods of

bohemianism, but yesterday’s bohemia was always more interesting and

productive in the eyes of those who experienced it.

It’s easy to understand why Roskolenko may have looked askance at some of

the posturings of the Beats of the 1960s. He’d led quite a colourful life.

Born in 1907 to Jewish immigrant parents on the Lower East Side of New York,

he ran away from home when he was 13 and in the early 1920s became a

merchant seaman. He wrote about this period of his life in a wonderful

memoir, When I Was Last on Cherry

Street, published in 1965. In the 1930s he aligned himself with the American

Trotskyists, and began to establish a reputation as a poet alongside Kenneth

Rexroth, William Carlos Williams, and Louis Zukofsky in avant-garde

magazines like Blues and

Pagany. He also hiked across

America, attempting to spread the revolutionary word. In the 1940s he joined

the Navy and served in the Pacific. After the war he travelled, wrote

novels, three memoirs, including the one referred to, and various other

books. I’m dealing with his activities in a very limited way. There isn’t

the space here to go into details about all the things he did and the people

he met. Roskolenko died in 1980.

Chandler Brossard also had a varied career, although of a different kind to

Harry Roskolenko. He was born in 1922 in Salt Lake City to “educated Mormon

elite and upper middle-class” parents. He moved to Washington with his

mother when his parents divorced, and seems to have dropped out of formal

education at the age of 11. When he was 18 he got a job with the

Washington Post and later worked

for the New Yorker, which is when

he started to think seriously about writing fiction. In the 1950s he had

editorial positions at leading magazines such as

Time, Life, and

Coronet. In 1955 he edited the

anthology, The Scene Before You : A

New Approach to American Culture, which included essays by writers like

Seymour Krim, Manny Farber, Harold Rosenberg, Lionel Trilling, Elizabeth

Hardwick, Clement Greenberg, Anatole Broyard, Milton Klonsky, Norman

Podhoretz, and others.

The inclusion of Broyard, Krim and Klonsky points to Brossard’s familiarity

with the Greenwich Village of the late-1940s and his novel,

Who Walk in Darkness, was

published in 1952 in the United States, but not before there had been

threats of legal action unless certain alterations were made. The main

problem centred around a character called Henry Porter who was allegedly

based on Anatole Broyard. The opening sentence stated, “People said Henry

Porter was a ‘passed’ Negro”, and Broyard’s parents were indeed black. But

he could easily pass for white, and it was useful to do that in the

racially-conscious atmosphere of America in the 1940s and 1950s. He was

publishing stories and essays in magazines like

Partisan Review,

New World Writing and

Discovery, and in due course

would become a regular reviewer for the

New York Times. His

posthumously-published Kafka Was The

Rage: A Greenwich Village Memoir, came out in 1993.

Brossard solved the dispute over the opening of

Who Walk in Darkness by changing

it to “People said that Henry Porter was an illegitimate”, and the book duly

appeared in 1952. It has been described as the first Beat novel, though it

isn’t about them. What it does deal with is the Greenwich Village scene of

the late-1940s and the young writers and intellectuals who gathered there. A

good description of that milieu can be found in Seymour Krim’s brilliant

essay, “What’s This Cat’s Story”. It was a competitive environment and

marked by its move away from the political tensions of the 1930s and the war

years. There may have been a few writers still involved with supporting

strikes, communism, and such matters, but there is no evidence of it in

Brossard’s novel or in Krim’s essay.

Brossard went on to publish several more novels, some of them –

The Bold Saboteurs and

The Double View – as hardbacks

with established New York publishers, while others –

Episode with Erika, The Girls in

Rome, A Man for all Women –were pulp paperbacks. The latter title was

actually a re-working of the 1954

Paris Escort by Daniel Harper, and

Episode with Erika had been

published in 1954 under the title All

Passion Spent. What this points to is a writer struggling to make a

living and turning to various strategies to bring in some earnings. In the

1960s he edited a number of paperback anthologies of short stories. The

titles, among them In Other Beds,

Marriage Games, Desire in the Suburbs, were obviously aimed at the pulp

market, but the writers included Chekhov, D.H. Lawrence, Turgenev, George

Eliot, as well as some of Brossard’s contemporaries like John Cheever,

Philip Roth, Richard Yates, and Herbert Gold. Brossard usually put in one of

his own stories, often under a pseudonym, which may have been a useful way

of pulling in a few extra dollars.

I have to say that I found Brossard’s later work of less interest.

Wake Up, We’re Almost There, a

sprawling, uneven novel, gained a degree of attention, but didn’t sell. He

produced a number of curious collections of short pieces that were published

by small, independent presses. One of them, Redbeck Press, was run by the

English poet and novelist, David Tipton, and as it happened he also

published three or four books of mine. I don’t suppose Brossard made much

money from these publications – Redbeck Press was hardly a money-spinner -

and he spent time as a writer-in-residence and similar positions at various

academic establishments, including Birmingham University in Britain. He died

in 1993.

I realise that, in some ways, I’ve moved away from pure pulp fiction as

practised by those writers who produced nothing but pulp and made no claims

to creating anything beyond it. There were plenty of them, and not all they

wrote can be easily dismissed. At their best they did what writers ought to

do and kept readers interested and keen to know what comes next. They could

establish strong characters, describe striking scenes, and invent effective

dialogue and intriguing plots. And they were entertaining. Just from that

1940s and 1950s period that interests me most I’ve enjoyed books by Gil

Brewer, Jim Thompson, Day Keene, Wade Miller, Steve Fisher, and Ed Lacy, to

name only a handful of the writers.

NOTES

For information about Harry Roskolenko it’s useful to look at his three

memoirs, and especially When I was

Last on Cherry Street (Stein and Day, New York, 1965). The others were

The Terrorized (Prentice-Hall,

New York, 1967), The Time That Was

Then : The Lower East Side 1900-1913 – An Intimate Chronicle (The Dial

Press, New York, 1971). For information about his poetry, and its

background, it’s best to refer to Andrew Crozier’s excellent essay, “The

Case of Harry Roskolenko” in his

Thrills and Frills: Selected Prose, edited by Ian Brinton (Shearsman

Books, Bristol, 2013). An obscure item of interest worth tracking down is

the obituary Roskolenko wrote about the New York bookseller and poet Harold

Briggs, whose bookshop, Books ‘n

Things, stocked little magazines and radical and

avant-garde literature. As Roskolenko, a friend from the 1930s, said,

“Harold and I hated every aspect of fascism, in and out of books”. It was

published in The Wormwood Review 40

(Stockton, 1970), edited by Marvin Malone.

The best source for information about Chandler Brossard and his various

publications is the Spring 1987 issue of

The Review of Contemporary Fiction,

devoted to him and edited by John O’Brien (Elmwood Park, 1987). It has a

bibliography of his novels, short stories, and selected essays, along with

an interview and a number of essays and commentary by other writers.