|

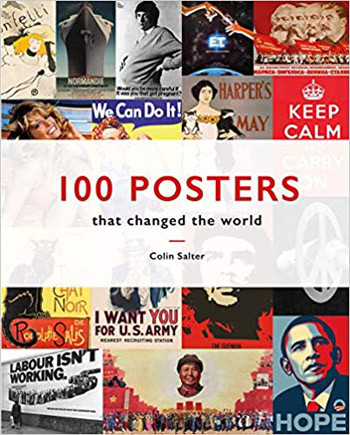

100

POSTERS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD

By Colin Salter

Pavilion Books. 224 pages. £14.99. ISBN 978-1-911641-45-2

Reviewed by Jim Burns

Posters are always all around us. When I’m out and about these days

they’re telling me to wear a face mask, wash my hands regularly, and

stay a safe distance from other people. If I look back seventy-five

years I can recall posters that told people to “Dig for Victory”

(the image of a booted foot pressing down on a spade has stayed in

my mind) and warning them that “careless talk costs lives”. Posters

such as these signify just one use of them- to keep us alert to

possible dangers – but there have been plenty of other posters,

providing information, entertainment, propaganda, that have adorned

walls, windows, and a variety of places where passers-by might see

them. That’s the idea of a poster – to catch your eye and tell you

something. Colin Salter refers to the Russian poet Mayakovsky, who

said, “that if a poster could not bring a running man to a halt it

had not done its job”.

In its simplest form a poster may just contain text. Salter

reproduces a proclamation that was issued by Parliament for the

apprehension of “Charls Stuart” (the future Charles the Second)

following the Royalist defeat at Worcester in 1651. It’s plain and

straightforward in its presentation, and if displayed in a public

place would presumably have been read aloud for the benefit of those

who were unable to read. By contrast, a 1930s poster advertising

rewards for information leading to the capture of the notorious

gangster John Dillinger, had not only photos of him but also the

sums of money involved highlighted in larger lettering. The aim of

both posters was the same, to lead to an arrest, but technology had

made it possible to change ways of attracting the attention of

likely informants.

It was technology, primarily the development of lithography and the

use of colour, that led to the explosion of poster displays in the

late-nineteenth century. The posters that Toulouse-Lautrec created

to publicise The Moulin Rouge and its performers have shaped our

ideas of 1890s Paris to the point where it’s almost impossible to

think of that era without one of his posters in mind. But he wasn’t

the only artist producing posters to celebrate the clubs and

cabarets of Montmartre. Théophile Alexandre Steinlen’s poster

advertising Le Chat Noir, with its defiant-looking black cat staring

at the viewer, and what appears to be a halo of sorts around its

head perhaps mocking the work of Alphonse Mucha, seems to me

important in terms of typifying a specific period in Paris. It might

also be appropriate to mention Jules Chéret. He was one of the most

prolific poster artists of his time

and the pretty girls he portrayed became known as Cherettes and

achieved great popularity among Parisians.

Posters were not only known for their links to Montmartre and its

night-time entertainments. The late-nineteenth century saw the rise

of a middle-class with money to spend on more than the basic

requirements of life. Advertising, as it always is, was directed

towards those with the funds and the time to frequent cafés and

other leisure centres. Posters advocating the pleasures of alcohol

of one kind or another could be seen in the streets. Salter has one

for absinthe which is quite provocative in its way. It shows a

couple seated at a table with the well-dressed man watching a young

woman tentatively sipping at a glass of the green liquid. Is there

something in his look that suggests seduction? Salter at one point

talks about “persuasion by association” and it could be that was

what was in the mind of the artist. Persuade a woman to drink

absinthe and she’s yours? Suggestion can be a key factor in

advertising. Were the 1940s/1950s advertisements for Chesterfield

cigarettes only drawing attention to the product when they used

phrases such as, “Like your pleasures BIG?” and “Man-Size

Satisfaction”?

Good-looking females were and still are a standard item in

advertising. Males, too, though the emphasis has mostly been on

women. I’ve mentioned Chéret’s pretty girls and their roles in

pushing various products and much later PETA (People for the Ethical

Treatment of Animals) put a nude model on a poster protesting

against the use of fur. Not everyone was happy about it. They felt,

not without reason, that there was a doubtful aspect to illustrating

a message with a picture of a naked woman. And wasn’t it likely to

pull attention away from the message and focus it on her body? I was

intrigued by what Salter describes as “the biggest-selling poster of

all time, shifting 20 million copies”. It’s of Farrah Fawcett in a

red swimsuit, and according to Salter “adorned the bedroom walls of

many adolescent boys”. It’s quite innocuous, especially by today’s

standards, though might have been thought daring when I was a

teenager.

The fact that it “shifted 20 million copies” points to how posters

became items manufactured for sale and decoration rather than for

use in advertising. Almost from the start they had been sought after

by collectors, and it didn’t take long for galleries to mount

exhibitions of posters, and for shops that sold them to open. In the

early days it’s said that posters would often be removed almost as

soon as they’d been pasted up on walls and hoardings. The thieves,

if that’s what they were, had an eye to the artistic qualities of

posters by Toulouse-Lautrec, Chéret, Steinlen, and others. Or

perhaps realised that they would increase in monetary value as the

years passed.

There was often a serious purpose behind the production of posters.

They weren’t all designed to sell silk stockings, bicycles, beer,

and biscuits. Political posters came in a variety of forms, ranging

from encouragement to vote in a certain way to emphasising the solid

virtues of a leader. The cult of personality that surrounded Stalin

was accented in numerous examples of the stern but just leader, the

friendly leader, and the wise leader. Salter uses one or two good

ones to illustrate his comments. One shows Stalin holding a small

child waving a flag. His look is benevolent. I recall a few years

ago seeing an exhibition of Soviet social-realist art at the Russian

Museum in Málaga, and it struck me that Stalin seemed to be in just

about every other painting. He was seen addressing workers on

collective farms, chairing meetIngs of the Politburo, and poring

over documents. None of the representations of the Great Leader

naturally gave an indication of his lust for power and his

cruelty. As with an advertising executive constructing an

image for a politician only the positive could be emphasised.

With political posters it is always possible to draw attention to

negative matters. Salter uses the famous (perhaps infamous,

depending on your political leanings) Conservative Party poster,

“Labour isn’t Working”, which showed what appeared to be a queue

trailing back into the distance while the head of the

queue enters the Unemployment Office, or the Dole as I would

have known it. It was, like it or not, a striking and effective

image and may have been at least partly responsible for the Tories

winning the 1979 General Election. Salter has some interesting

things to say about how Saatchi & Saatchi created this poster. If

questions can be asked about some of his choices of posters and

their supposed impacts, there’s no doubt that this one did

contribute towards change.

War being politics by other means, posters plainly come into their

own when it’s necessary to persuade people to join up, work harder,

make sacrifices, and generally fall in behind whichever government

wants their support. There are famous posters which seem to

represent the mood of the moment, such as that of Kitchener pointing

his finger towards whoever is looking at the poster and demanding

that he should “Join Your Country’s Army”. It appeared in 1915 as

the need for men became increasingly obvious. From the Second World

War, and more to do with the home front in the United States, there

was the well-known “Rosie the Riveter” poster which celebrated the

role that women had to play by replacing men in the factories

turning out tanks, planes, and other armaments.

Motivating the civilian population was a concern in wartime, and in

1915 worries extended to the effect that alcohol consumption was

having on factory workers, miners, and many others. Lloyd George

proclaimed on a poster that “We are fighting Germany, Austria and

Drink…..and the Greatest of these three Deadly Foes is Drink”. It

was during the First World War that the licensing laws we lived with

for so long were brought into effect. At the time of the Second

World War there were poster campaigns to warn servicemen of the

dangers of sexual diseases: “You can’t beat the Axis if you get VD”.

The wars, First and Second, did allow may women to lead independent

lives, though the post-war situations often found that independence

under attack. It wasn’t just a case of men not liking the idea of

women doing jobs that had traditionally belonged to them. Their

new-found confidence made men feel uneasy. But any attempts by women

to move out of their “proper” roles had long been frowned on, as the

Suffragettes discovered when they agitated for the vote. Salter

presents posters from both sides of the story, with one

demonstrating what happens when working-class women get mixed up

with suffragette concerns and as a result neglect their homes and

children. Of the pro-suffragette statements I like an American

example where Rose O’Neill employed her Kewpie characters from the

strip cartoons she did for

The Ladies Home Companion and other publications for a poster on

which they ask that their mothers be given the vote: “Isn’t it a

funny thing/That father cannot see/Why mother ought to have a

vote/On how these things should be?” The “things” were food, health,

schools and other matters affecting children. The Kewpies were cute

and popular and would have caught the attention of the general

public.

Salter’s survey doesn’t only look at posters from the past, and in

fact his book has one from a 2019 Extinction Rebellion campaign. It

could, perhaps, be argued that the period from 1960 on has been a

golden one for poster designers and printers. The 1960s had a

resurgence of Art Nouveau which tied in easily with the psychedelic

layouts favoured by the so-called “underground” with its hippy

devotees. Posters advertised Woodstock and rock music. Out of the

same era came posters opposing the Vietnam War and stirring up

events in Paris. Film posters explored new angles, exploiting sex

and shock tactics to make people stop and, hopefully, think they

might like to see the film concerned. Salter uses a poster

advertising Jaws, with

the shark’s teeth prominently displayed.

It’s always been debatable if poster art, which is essentially

commercial art, can, at its best, be moved into a fine art category.

There are all kinds of interesting questions raised in this

connection. If I see a poster advertising an exhibition of a famous

artist’s work, and on which there is one of his paintings, has that

work been reduced in status by its use for a commercial purpose? I

doubt that any of us would think so. And we now happily accept

Toulouse-Lautrec’s work as art, even if it was done for the purpose

of advertising. I have to say that I’ve seen posters, many of them

skilled in their drawing and painting techniques, which seem to me

to be more interesting than a lot of the routine portrait and

landscapes found in galleries. Remove the brand name or slogan from

a poster and it could be viewed as a work of art and not just an

advertisement.

Colin Salter has put together an entertaining and informative book.

It covers much more ground than I’ve been able to indicate in this

review. Liberally illustrated, and with useful accompanying text, it

provides a good guide to the qualities and uses of posters.

|