|

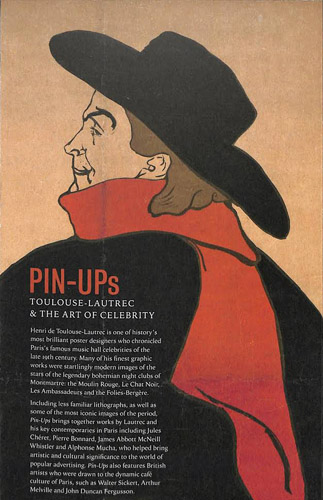

PIN-UPS: TOULOUSE-LAUTREC AND THE ART OF CELEBRITY

An exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery,

PIN-UPS: TOULOUSE-LAUTREC AND THE ART OF CELEBRITY

Edited by Hannah Brocklehurst and Frances Fowle

National Galleries of

As the introduction to the excellent catalogue for this exhibition

points out, a “culture of celebrity” is not something that suddenly

appeared around the mid to late-twentieth century when the world of

pop began to demonstrate how important publicity was to the success

of many musicians and singers. Back in the

In

The fact is that faded photographs, scratchy recordings, and a few

similar mementos apart, little exists of the work of most of the

performers to persuade us that they were as good as contemporaries

claimed them to be. We rely on the posters to recreate what we

imagine they were like. Interestingly, the value of many of the

posters as art, and not merely as advertisement, seems to have been

recognised almost from the start as technical innovations, and a

loosening of licensing laws, caused them to proliferate. People went

out and stripped them from walls and hoardings almost as soon as

they were put up. Exhibitions of poster art were organised, dealers

began to specialise in them. The first poster exhibition took place

in Paris in 1884, and a major one In London in 1894/95. I don’t

think we ever had any poster artists in this country to compare with

Lautrec, Jules Chéret, and Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen. They were

among the leading names, along with Alphonse Mucha, who largely

specialised in advertising Sarah Bernhardt, but many other artists

produced posters, if not to the same degree as Lautrec. Pierre

Bonnard is an example. Designing posters presumably paid reasonably

well and could help support struggling younger artists.

It is Lautrec who occupies the key role in the exhibition, and more

than a few of his best-known posters can be seen on its walls.

Aristide Bruant, Yvette Guilbert, La Goulue, and Jane Avril. They’re

all there. He also portrayed some lesser-known performers, such as

May Milton and May Belfort. The latter had a brief success with the

song, “Daddy Wouldn’t Buy me a Bow-Wow”, though her career failed to

develop after that. If the song is ever heard now I doubt that many

people will know who first sang it. As for May

There are other posters and paintings in the exhibition that are

well worth mentioning. Jules Chéret’s design for LoÏs Fuller’s

appearance at the Folies Bergère is eye-catching. Fuller, an

American, specialised in dancing while “dressed in reams of white

silk, with wands sewn inside the sleeves, she would swirl the fabric

to create spectacular sculptural forms”. Henri-Gabriel Ibels’ poster

for “the popular entertainer Jane Debary” is less colourful than

Lautrec and Chéret, but is still striking. And Steinlen’s brilliant

poster, “Cabaret of the Chat Noir with Rudolph Salis”, is a

stand-out item. He amusingly mocked Alphonse Mucha’s liking for the

halos he often placed around the heads of his females by showing his

cat with one.

Two small, but typical Daumier lithographs, a 1930s painting by

Sickert of high-stepping chorus girls, and his early 1900s, “The Old

Bedford”, a music-hall he frequented, and several works by the

Scottish colourist, John Duncan Ferguson are bonus items. I was

particularly taken by

Pin-Ups: Toulouse-Lautrec & the Art of Celebrity

doesn’t break any new ground, but it is a thoroughly entertaining

and in some ways instructive exhibition. The emphasis is obviously

on personalities, but posters also played a key role in advertising

products. Bonnard’s poster promoting a brand of champagne is a

notable example.

|