|

THE PRIVATE LIVES OF PICTURES : ART AT HOME IN BRITAIN 1800-1940

By Nicholas Tromans

Reaktion Books. 294 pages. £25. ISBN 978-1-78914-623-3

Reviewed by Jim Burns

I grew up in a house without pictures. I’m not sure why there were

no paintings or other illustrations on the walls or even on the

sideboard or mantelpiece in the form of photographs. Nicholas

Tromans tells the story of Jeanette Winterson’s “severely

fundamentalist mother” who wouldn’t display some paintings she had

inherited. My own

mother came from quite a strict Baptist background in the Cumberland

coalfields, but I doubt that she had a particular aversion to

pictures. It was more likely that a lack of money meant that

pictures were not seen as essential. And she certainly would never

have considered clipping something out of a magazine and tacking

that on the wall. Advertising your poverty, no matter how real it

was, was not something you did.

I did see pictures as I got older. The local combined library and

art gallery was always open and wandering around the different rooms

opened my eyes to what paintings could do. I can still see one or

two of the canvases from seventy and more years ago in my mind’s

eye. In a way I’m glad that there weren’t pictures at home. They no

doubt would have been fairly innocuous, had they existed, and I’d

have been so used to them that they would have lacked any kind of

meaning beyond the merely decorative, and perhaps not even that.

Even a home well-stocked with paintings might not have appealed.

A profusion of pictures in a

small room can often confuse me and I prefer a single painting in a

domestic setting. On the whole, however, I choose to view paintings

in galleries and even there like to see them well spaced out.

Tromans’ engaging book by its very nature looks closely at what the

more-affluent classes chose to hang on their walls. There is little

consideration of what was on display further down the social scale.

He’s not to be condemned because of this. It’s doubtful if much

documentation exists of what, if anything, working-class people

owned in the form of paintings. Lower middle-class families wanting

to show how respectable they were might well have had a painting on

display in their living-room. And the more-ambitious, moving into

the managerial range of employment, might well have gone even

further and had more than one painting prominent. I’m generalising,

and exceptions must always have existed, especially if the

definition of a “picture” is extended to include prints and

illustrations of one sort or another taken from magazines and

newspapers. And why not photographs? They were easier to obtain as

commercial photography developed. When I was small in the

early-1940s I was often looked after by an old lady. I don’t

remember any paintings in her house but there were photographs of

her sons who had been killed in the First World War,

I think it’s of interest to note, in the context of what the

less-affluent might have experienced in connection with paintings, a

few lines from O. Henry’s supernatural story, “The Furnished Room” :

“Upon the gay-papered wall were those pictures that pursue the

homeless from house to house – ‘The Huguenot Lovers’, ‘The First

Quarrel’, ‘The Wedding Breakfast’, ‘Psyche at the Fountain’ “. I

think I may have seen at least a couple of these, or something

similar to them, over the years.

So, with Tromans, we are taken through an imaginary house and told

what was seen as suitable for hanging on the walls. He illustrates

his tour with references to real rooms in the homes of the

well—to-do and intellectually active. The aristocracy could afford

to purchase pictures and sometimes commission them, and the poets

and writers would have had friends and acquaintances who were

artists and so be in a position to obtain paintings at reasonable

prices and sometimes as gifts. But inevitably it’s mostly the

upper-classes whose houses were filled with paintings. How often

they were looked at might be another matter. The rooms in some of

the photos in the book seem cluttered to me and not just with

paintings. The furniture and ornaments take up a lot of space and

surely would have distracted from any consideration of the art other

than at a superficial level. The writer George Moore perhaps got it

right when he suggested that “all important old paintings” ought to

be in galleries and not in domestic settings.

It’s interesting to follow Tromans as he categorises the kinds of

paintings in the various rooms. The hallway was not seen as

somewhere to hang anything significant. Few people linger there, so

what’s the point in displaying anything worth more than a cursory

glance? I’m not just referring to Tromans’ views and he cites

critics and commentators who claimed to provide expert advice on how

to get the best from pictures in terms of deriving pleasure from

them or presumably just impressing visitors. There were publications

designed to guide people into the world of “good taste” by

indicating which wallpaper was best suited to certain pictures. It

wasn’t a case of simply finding a convenient spot to hang a picture.

Its colours had to combine and not clash with those of the space

surrounding it.

There were discussions about which pictures might be hung in the

dining-room. Nothing too striking in case they diverted attention

away from the talk around the table. Bland family portraits,

perhaps, though those could also be used on a staircase. Very few

people, ascending or descending, would bother to pause and look

closely at a picture of some old man or woman. So, the better

pictures, those with impressive painterly qualities, or at least

some notable financial value, might be allocated places in the

library or living-room.

And the bedroom? Ah, the adventurous might have a slightly

provocative painting there, but nothing likely to shock the female

members of the family or the servants.

Generally, it would seem that the bedroom was not considered a

suitable place to hang paintings of any kind. And throughout the

house the controversial was avoided. PaIntings created their own

world of serenity and calm and the world outside of mills and mines,

and the people who worked in them, wasn’t allowed to intrude into

middle and upper-class domesticity. To be fair, it’s not likely that

working-class families would want to be reminded of where they had

to go during the day. If they had anything on the walls it could be

of flowers and fields, or somewhere exotic. Tromans points to D.H.

Lawrence’s play, A Collier’s

Friday Night, where a picture of Venice hangs over the

mantelpiece.

“By the last years of the nineteenth century”, says Tromans, “the

sense of the picture being an ‘alien’ in the home promoted a late

flowering of the gothic picture tale”. Oscar Wilde’s

The Picture of Dorian Gray

is one of the best-known in the genre, though it had a

predecessor in Charles Maturin’s 1820 novel, Melmoth the Wanderer.

There can be something unnerving about a portrait of someone staring

out at the viewer and even giving the impression of the eyes

following one’s movements. This could have been another reason for

hanging portraits where few people would bother to look at them. An

obscure 1890s ghost story, Ralph Adam Cram’s “In Kropfsberg Keep”,

says that “the stiff old portraits changed countenance constantly

under the flickering firelight”.

But I like the Thomas Hardy story, “The Enemy’s Portrait”, where,

Tromans tells us, “the narrator finds at an auction the portrait of

one who had done him a terrible wrong. After he had bought it with

the intention of burning the canvas and reusing the frame, the

picture is laid against a wall pending its destruction, but, being a

trip hazard, it is hung by a servant on the wall, where it is

forgotten, eventually outliving the embittered owner”. Moving away

from portraits, M.R. James’s “The Mezzotint” shows what can happen

when a landscape which includes figures takes on a life of its own.

The reference to the frame in the Hardy story takes me to a section

of Tromans’ book where he discusses frames and their uses. I tend to

like frames which are plain and functional and don’t overwhelm the

canvas. Looking at old paintings in charity shops and second-hand

dealers, where I suspect they come from house clearances, I’m

inclined to the view that the frame was, for some householders,

often more important than the picture. And lent itself to the

interpretation that it was simply an extension of the general

decorative scheme. Rather in the way that much abstract art,

especially of the colour field variety, has become in large offices

and the like. Little to do with art and more to do with creating a

soporific effect guaranteed not to disturb anyone.

If frames were, or should have been important then the way a picture

was hung should have been equally so. Flat against the wall or

slightly tilted forward? Tromans examines the procedures open to the

home-owner anxious to establish the right effect. And the types of

hooks and other devices used. It wasn’t just a matter of knocking a

nail in a wall, at least not in homes where appearances counted.

As new techniques relating to prints began to appear the possibility

of having something on the wall became open to a wider public. Not

everyone was in favour of this, feeling that the mass reproduction

of well-known works of art lowered their value, not only in monetary

but artistic terms. But something like the Autotype (“a

photomechanical printmaking process using light-sensitive gelatine

to reproduce the intermediary tones of a transparency of an initial

photograph”.) helped

popularise art, again not something that purists and highbrow

critics necessarily liked. In a way it was taking art out of their

control and they were in danger of no longer being needed for

consultation about what was recommended

for the home. People just exercised their own judgement and

bought what they enjoyed in cheap versions : “For those with taste

but limited funds, the autotype was the passport to authentic art in

the house”.

Tromans refers to the department store, Whiteleys, which issued in

instalments “domesticated versions of the famous masterpieces of the

great galleries of the world.......For at least one Edwardian

working-class memoirist, tacking up a selection of these in his new

lodgings was a symbol of having escaped the slums”. He also brings

in another aspect of the working-class use of pictures: “Dan Cullen,

a London docker thrown out of work for his union activism, was found

dying in his filthy Whitechapel room around 1900, looking up at his

collection of cheap portraits of Engels, John Burns and other heroes

of labour”.

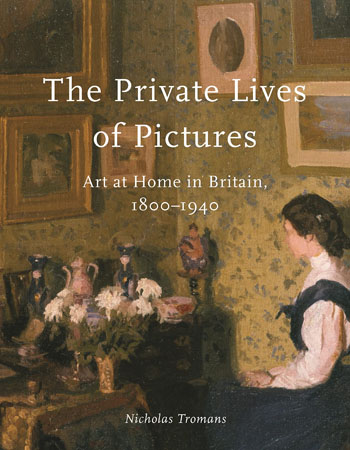

The front cover of The

Private Lives of Pictures reproduces a Harold Gilman painting,

“Edwardian Interior” which shows a young woman seated at a table and

studying the items on it. Tromans wonders how many people

“truthfully, really looked at the pictures in their home on a

regular basis?” and then suggests that Gilman’s painting “was surely

more common – the pictures reassuringly present but the occupants’

attention fixed on the tangible, operable objects of the home”.

Well, perhaps, though the lady may have looked at the pictures

before she sat down, or will look at them when she gets up. And, in

any case, why should she be expected to look at pictures all the

time? Looking at a picture ought to be a pleasurable experience and

not just a duty. I’m

having a little fun here, but making what I think is a serious point

about how and why people appreciate art. Not everyone wants to be a

specialist.

Nicholas Troman’s has written a thoroughly interesting and at times

provocative book which moves away from the standard texts of art

history and analysis. HIs account of the roles that art fulfilled in

private homes is immensely readable and offers a great deal of food

for thought. There are ample notes and some useful illustrations.

r

|