|

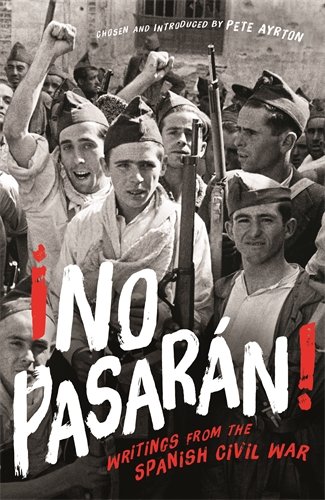

NO PASARÁN: WRITINGS FROM THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR Chosen and introduced by Pete Ayrton Serpent’s Tail. 393 pages. £20. ISBN 978-1-84668-997-0 Reviewed by Jim Burns

The literature of the Spanish Civil War is voluminous. Histories, essays, novels, short-stories memoirs, poetry, plays, and much more. I suppose most readers will be familiar with at least two books in English, Ernest Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls and George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia, and the exploits of their writers. There are many others, some of which focus on the International Brigades, the units of foreign volunteers fighting for the legally-elected Republican Government against General Franco and his co-conspirators. They make for informative reading. On the other hand, all these books, and many pamphlets, articles, and other written sources, are largely concerned with what might be called the non-Spanish contributions to the narrative. And most of them are written from a pro-Republican point of view. We rarely get to read Spanish writers in general, and we’re especially starved of work by those who supported Franco. The difference between the material referred to above and No Pasarán is that the emphasis in the latter is on Spanish writers. There are, it’s true, some well-known names – George Orwell, Arthur Koestler, Sartre, Laurie Lee, André Malraux. I was going to add John Dos Passos, but I wonder how many people read him these days? And some lesser-known writers – Muriel Rukeyser, Gamel Woolsey, Esmond Romilly – are among the English-speaking contributors. The rest, give or take a handful of writers from Italy, Poland, etc., are Spanish. It’s perhaps worth noting at this point that there is little in No Pasarán about the International Brigades. I’m second to no-one in my admiration for the men and women who served in the Brigades and suffered, in more ways than one, because of that fact, but we do need to know much more about how Spaniards responded to events. When the war started in 1936, the Republic was badly prepared to meet the threat from Franco. He had the support of what were some of the most effective fighting units in the Spanish Army. They were the Spanish Foreign Legion, and the regiments of the Army of Africa, which included Moorish troops. Both the Legion and the Moors were noted for their ferocity in battle. Franco was also soon supported by Hitler, who sent the Condor Legion, with crack airmen, to Spain, and Mussolini, who provided up to 80,000 troops, complete with tanks and artillery. There is an informative book, Franco’s Foreign Legions Adventurers, Fascists, and Christian Crusaders in the Spanish Civil War by Christopher Othen (Hurst & Co., 2013) which provides a great deal of information about who fought for Franco. Othen, for example, says that around 78,000 Moors served in the Nationalist army. The Republic, by contrast, had to rely largely on some loyal soldiers and policemen, but also on militia units formed around political parties and trade unions. Initially, at least, the workers were denied arms, but when the Government realised the gravity of the situation, rifles and other armaments were issued to them. Further problems were caused by the hypocritical Non-Intervention policies practised by countries such as Britain, France, and the United States. The only two countries prepared to supply arms and ammunition to the Republic were Russia and Mexico, but at first the quality of what was provided was poor. Old rifles and machine guns, and defective ammunition, were common, and when added to the lack of training and discipline, the situation quickly became chaotic. It’s frankly amazing that the Republic didn’t completely collapse within a few months, if not weeks, of Franco launching his offensive. The film director, Luis Buñuel, was in Spain when war was declared, and the excerpt from his autobiography, My Last Breath, describes what it was like: “The first three months were the worst, mostly because of the total absence of control………No sooner had the people risen and seized power than they split into factions and began tearing one another to pieces. The insane and indiscriminate settling of accounts made everyone forget the essential reasons for the war.” Buñuel also recounts an encounter with border guards who refused to recognise documents issued by the Republican Government and said he had to have a visa from local anarchists. Just prior to that he had shared a railway carriage with a POUM officer who stated that the Government was “garbage and had to be wiped out at any cost”. The POUM were non-communist Marxists and often referred to as Trotskyists, and like the anarchists would eventually fall foul of the communists. They were beginning to take over control of some key government positions, especially as Russian aid began to play a significant role in helping the Republican forces to continue holding back Franco’s army. I have to say that the anarchists do not come out well, on the whole, when reading through the various pieces in No Pasarán. Buñuel describes an incident in a town called Calanda. According to his account the anarchists executed eighty-two people: “Among the victims were nine Dominicans, most of the leading citizens on the council, some doctors and landowners, and even a few poor people whose only crime was a reputation for piety”. And the Franco supporter José María Gironella’s The Cypresses Believe in God, a novel described as “an ambitious attempt to capture the war on both sides”, has a vivid description of mobs led by anarchists burning churches. It’s necessary to point out that anarchist excesses and atrocities were equalled on the Nationalist side, which doesn’t make them any better or worse, but does indicate the high levels of hatred and bitterness that were an integral part of the war in Spain. Summary executions were a feature of the activities of both sides. The Basque, Bernardo Atxaga, was too young to participate in the war, but in his De Gernika a Guernica, he tells of reading in a newspaper the reminiscences of an old man from Fuenteguinaldo: “Apparently, the Falangists asked the priest to draw up a list of all the reds and atheists in the village. On October 7th, 1936, they went from house to house looking for them. At nine o’clock at night they were taken to the prison in Cuidad Rodrigo, and at four o’clock in the morning, were told they were being released, but at the door of the prison a truck was waiting and, instead of taking them home, it brought them here to be killed”. There’s a telling comment in a well-written and sympathetic (to the Republic) article, “The Villages are the Heart of Spain”, that John Dos Passos wrote for Esquire in 1937: “How can they win, I was thinking? How can the new world full of confusion and crosspurposes and illusions and dazzled by the mirage of idealistic phrases win against the iron combination of men accustomed to run things who have only one idea binding them together, to hold on to what they’ve got”. Earlier Dos Passos had talked about a village he visited where the socialist U.G.T. was at odds with the syndicalist C.N.T. regarding the direction to take and the need for reform or revolution. The syndicalists, like the anarchists, believed that the war was an opportunity to push through a social revolution as well as defeat Franco. The Italian anarchist Antoine Gimenez, who fought with the Durutti Column, wrote a memoir, Sons of the Night, in which he described an anarchist giving a talk on “free love” to an audience of local people. One can imagine the “confusion” in the minds of people probably brought up in an atmosphere of strict social and moral control as they heard the idealistic statements of the speaker. And the “crosspurposes” his words might have induced as they wondered what defeating Franco had to do with looking favourably on one’s wife having a lover. The realities of war are described in more than one piece. Many soldiers have noted that war is often ninety-five percent boredom and five percent terror (the statistics may vary slightly, according to experience), and poor food, which was often in short supply, a lack of cigarettes, and lice, were fairly standard complaints. Mika Etchebéhere joined a POUM unit, where she soon became its commander, to the consternation of its soldiers. They liked and admired her, but were worried about being teased by other troops because they were led by a woman. Her account of being infested with lice is told with humour, though one can imagine that the experience wasn’t a pleasant one. But neither was Esmond Romilly’s experience of battle. His “At the End of the Alphabet”, from his book, Boadilla, vividly describes the confusion and the fear, and the realisation that, though one has survived, several friends are dead. There is, perhaps, some humour to be drawn from many situations, and Arturo Barea’s “This War is a Lesson”, from The Clash, part three of his The Forging of a Rebel trilogy, does have an element of black humour. Barea had a friend, a priest who, when the war started, remained loyal to the Republic. One night a car drew up and several anarchists got out and told the priest to come with them. Knowing the anarchists’ reputation for killing priests, his friends protested and stressed that he was a loyal supporter of the Republic. The anarchists insisted that the priest had to accompany them, and eventually one of them said: “Oh hell, nothing will happen to him. If you must know, the old woman, my mother, is dying and doesn’t want to go to the other world without confessing to one of these buzzards. It’s a disgrace for me, but what else could I do but fetch him?” It’s worth noting that Barea’s trilogy has been available in English translation for some years. Its three books – The Forge, The Track, The Clash – describe his childhood, his service in the Spanish Army in Morocco in the 1920s, and his adventures in the Spanish Civil War. There may be some humour, too, to be derived from Curzio Malaparte’s “The Traitor,” which is about a group of young Spaniards who, having been sent to Russia as refugees during the Civil War, have grown up as staunch communists. They are captured by the Finns during the fighting beween Finland and Russia, but the Finns are at a loss as to what to do with them. They are offered the chance to return to Spain, but turn it down. One does eventually agree to return, and is turned on, and beaten up by the others. But he does go home and when he dies is buried as a Catholic. There are many fascinating accounts in No Pasarán. Pierre Herbart went to Russia with André Gide, and when the latter wrote a book critical of some aspects of the Soviet system, Herbart was sent to Spain to ask André Malraux’s advice about publication. While he was there, Gide, despite promises to the contrary, published the book. There was outrage in communist circles, and in the dangerous atmosphere in Spain Herbart came under suspicion for having played a part in getting the book into print while pretending to consult Malraux, a Party stalwart, about it. He did manage to get back safely to Paris, where Gide seemed more concerned about the favourable attention he was getting from the press and public than in what might have happened to Herbart. There is also a short piece by Drieu La Rochelle which in a non-pedantic way presents his case for Fascism and support for Franco. He at one time associated with the Dadaists and Surrealists, but moved right and collaborated with the Germans when France was occupied. He went into hiding after the Liberation and committed suicide in 1945. No Pasarán is a splendid collection and the fact of it having such a variety of writers, many of them Spanish, adds to its interest and usefulness. On my shelves is a book called Cries From a Wounded Madrid: Poetry of the Spanish Civil War, selected and translated by Carlos Bauer (Ohio University Press, 1984). No Pasarán will make a good prose companion for it.

|