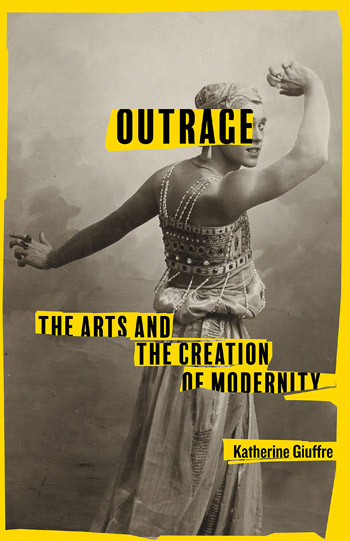

OUTRAGE : THE ARTS AND THE CREATION OF MODERNITY

By Katherine Giuffre

Stanford University Press. 200 pages. £21.99. ISBN 978-1-5036-3582-1

Reviewed by Jim Burns

When Picasso, “a twenty-five-year-old impoverished painter living in squalid

conditions in Paris”, exhibited

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907

the reactions were generally not favourable. The collector Leo Stein laughed

at what he referred to as a “horrible mess”, and the painter André Derain

said, “This can only end in suicide. One day Picasso will be found hanging

behind the Demoiselles”. Picasso

put the canvas away and only displayed it again in 1916. But, points out

Katherine Giuffre, it “became one of the most important paintings of the

twentieth century”.

Giuffre refers to some other examples of works now considered of importance

which were initially either dismissed or ignored: “Moby

Dick was so unpopular that it effectively ended Herman Melville’s

flourishing writing career”. And Henry David Thoreau’s books lingered in

their publisher’s warehouse until he bought the unsold copies to save them

from being pulped: “I have a library of nearly nine hundred volumes” he

said, “over seven hundred of which I wrote myself”.

The point she’s making is that the new and different very often aroused a

hostile reaction of one kind or another. There are plenty of other examples

she could have used. Van Gogh’s paintings only one of which sold in his

lifetime. Now you have to queue to see the blockbuster shows of his work.

But it’s interesting to look at why people, including many who were

otherwise intellectually active, viewed something unusual with suspicion.

Was it a simple lack of

understanding, or did they truly think that what they read or viewed or

listened to presented a threat to civilised living?

“And what rough beast, its hour come

round at last/Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born? ”, wrote W.B.Yeats. And

people rioted at the first performance by the Ballets Russe of Stravinsky’s

The Rite of Spring.

As a contradiction to neglect being a means of dismissing the new, Giuffre

chooses to look at the Brontë sisters and the ways in which their writings

were received by critics and the wider public. It seems to be true that

books like Jane Eyre, Agnes Grey,

and Wuthering Heights were

popular, at least with general readers. What really seems to have caused

controversy was the revelation that the novels, which were first published

under male names, had, in fact, been written by women : “The Brontës,

writing novels that passionately and unapologetically exposed the inner

lives of their protagonists, clearly violated every precept for femininity,

upended every rule for proper female decorum, and usurped every privilege

usually reserved for the male counterparts”.

There was also the question of the social and political implications of what

the Brontës wrote about and how they wrote about it.

Giuffre refers tellingly to a December 1848 review by Elizabeth Rigby

which savagely attacked Jane Eyre.

Bear in mind that 1848 was a significant year in terms of the revolutions

across the Continent and the political unrest in Britain. Rigby was in no

doubt about what was behind the novel: “We do not hesitate to say that the

tone of mind and thought which has overthrown authority and violated every

code human and divine abroad, and fostered Chartism and rebellion at home,

is the same which has also written

Jane Eyre”.

In France in the nineteenth century the Salon held sway when it came to the

standards set for anyone wanting recognition as a painter. The competition

for a place in its annual exhibitions was fierce, and in 1863, following

Napoleon the Third’s intervention, the Salon des Refusés was created so that

some of the artists whose work had been rejected could display their

canvases.

One of the paintings in the exhibition was Manet’s

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, now

considered a modern masterpiece but at the time causing consternation and

controversy. It showed a naked woman with two fully-dressed men gathered

around a picnic spread, and with another young woman in the background

washing herself in a stream. Giuffre points out that it was based on an

engraving by Raphael, but the matter of the men being clothed in

contemporary dress clearly changed the setting to a modern location. There

was also the fact that the naked woman in the foreground didn’t seem at all

embarrassed by the situation and was looking directly at the viewer in a

quite open manner. It was a kind of “Well, what are

you looking at?” stare that was

evident.

Among the criticism levelled at Manet was that, although talented, he

“persisted in reproducing repulsively vulgar subjects, scenes devoid of

interest”. And it was suggested that “All his efforts should be directed

towards expressing living nature in its most beautiful forms”. Like the

Brontës it was proposed that he “must be ill, either physically or morally”.

The work was said to be unhealthy. There were indications that he might have

been suffering from “an acute affliction of the retina”.

His work wasn’t alone in being attacked. The artists who generally became

known as Impressionists took a

beating. The majority of the reviews of the first Impressionist show in 1874

were hostile. They pointed to what they claimed was the “unfinished” nature

of the paintings, and there were jibes about “palette scrapings” and the

artists having “declared war on beauty”. Giuffre sees much of the reaction

as arising from the insecurity of the bourgeoisie who were unsure of their

place in society and therefore unwilling to hold themselves open to ridicule

by supporting something that had not received official approval. She directs

our attention to the fact that the Impressionists sold better in the United

States where “new money” had more confidence in its role.

Was Emily Dickinson “an eccentric, dreamy, half-educated recluse” writing

short-lined little verses that broke all the usual rules that applied to

writing poetry? And mostly

refusing to circulate them beyond her immediate friends and relations? The

story of how and why Dickinson’s poetry was written and what happened to it

when it fell into the hands of those determined to make it “respectable” is

well-known, but Giuffre manages to tell it again without losing the reader’s

interest. What was put into print after her death was not what Dickinson

intended in terms of layout, punctuation, and other factors. It was tidied

up by those who thought they knew best.

Giuffre is seemingly more concerned to deal with the story behind the poems,

the way Dickinson lived, who she knew, what she was interested in. There was

a long-standing relationship with Susan Gilbert which was effectively left

out of early accounts of Dickinson’ life. It’s still not really known what

the nature of that relationship was.

Instead, according to Giuffre, an image was created “of the author as

a timid and virginal recluse, uneducated in literature, writing from pure

instinct as a way to alleviate the broken heart she had suffered from some

mysterious unrequited love”. This was meant to give her work wider popular

appeal. But the critics still wrote against her. One said: “Miss Dickinson

in her poetry broke every one of the natural and salutary laws of verse.

Here is the very anarchy of the Muses”. But she followed her own path and

became a genuinely original poet.

A term like “Delirious Cocksuckers” might bring about a burst of outrage

from some sensitive readers, even now in our supposedly more-tolerant times.

It refers to the “kind of homosexual Swiss Guard” clustered around the

impresario Sergei Diaghilev and his Ballets Russe. He’d left St Petersburg

because he was openly gay in a society that wasn’t inclined to accept such

behaviour, and relocated to Paris where homosexuality wasn’t illegal.

Principal among his followers was the dancer Vaslav Nijinsky who, it was

said, often appeared to hang suspended in the air when he made one of his

fantastic leaps.

Diaghilev’s most famous triumph was the opening night of Stravinsky’s

The Rite of Spring in 1913. It

was almost a deliberate act of provocation and designed to create a

sensation and attract publicity. Which isn’t to suggest that was all it was:

“The sets and costumes were stunningly colourful, the music and choreography

were strikingly modern, and the dancers were energetic and powerful”. It not

only changed ballet by challenging the established rules about

subject-matter, tempo, and the techniques of dancing, it had an influence

“on the rest of the art world – not only music and design, but also fashion,

painting, and even poetry”. However,

the immediate effect was, as Diaghilev no doubt anticipated, that a riot

broke out in the theatre. Advocates of the new ideas in the arts, and their

traditional opponents, traded insults and blows while the musicians and

dancers did their best to carry on regardless of what the audience was

doing.

I think I ought to point out that Katherine Giuffre is a “specialist in the

sociology of art and culture and studies social networks and communities”,

so literary and art criticism isn’t at the forefront of her writing. When

she turns to how James Joyce’s

Ulysses was received she is largely concerned to deal with matters of

censorship. It was. she says, “bound up with social control in rapidly

urbanising societies where traditional mores no longer held sway and where

diverse populations mixed more frequently”. Her account of the legal battles

fought over the right to read what an enemy of the book described as

“damnable hellish filth from the gutter of a human mind” is brisk and

informative. Margaret Anderson, editor of

The Little Review, a standard

bearer for the modernist movement, was taken to court for using extracts

from Ulysses. Later, when the

book was published by Sylvia Beach from her bookshop, Shakespeare and

Company, in Paris, and imported into America, there were further legal

tussles until Ulysses was cleared

by the courts for open sale.

It’s notable that women were closely involved with the struggle to get

Ulysses into print and available

for anyone to read. Margaret Anderson, Sylvia Beach, and Jane Heap were

essential to not only the publication of Joyce’s work, but also in providing

support at a time when there was little coming in from other sources. A

couple of other things occur to me. One is that

The Little Review is worthy of a

study in itself. It was described in

The Little Magazine: A History and Bibliography (Princeton University

Press, 1946) as “one of the few outlets in this country for ideas and

techniques which were to influence profoundly much of our later writing”.

And on that question of “influence” it can still be a matter for debate

about the amount of influence Joyce had. And even whether or not that

influence was, when it came to straightforward questions of literature,

always for the good.

Giuffre looks at Zora Neale Hurston’s novel,

Their Eyes Were Watching God,

largely from the point of view of how it was criticised by members of the

black community in America. Hurston had grown up in a small town populated

by blacks, and had been a student at Howard University. She moved to New

York and was prominent in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. But when her

book appeared in 1937 it was seen by Richard Wright as being in “the

tradition which was forced upon the Negro in the theatre, that is the

minstrel technique that makes the ‘white folks’ laugh…….The sensory sweep of

her novel carries no theme, no message, no thought”. He accused Hurston of

pandering to white tastes. Another black writer, Ralph Ellison, likewise

found fault with Hurston’s portrayal of black lives. It might be relevant

that both reviews were published in the

New Masses, a Communist Party

publication. The Party was then keen to promote the interest of blacks,

provided they were in line with Party politics. And Hurston’s writing was

seen as “not serious” and “not political”.

Katherine Giuffre may not have broken any new ground with her study of six

examples of creative works that aroused opposition of one sort or another

when they first came to wider attention, but which, she avers, had a place

in the creation of modernism. However, she has produced a lively and

thoughtful account of how and why the new and different could cause outrage.