|

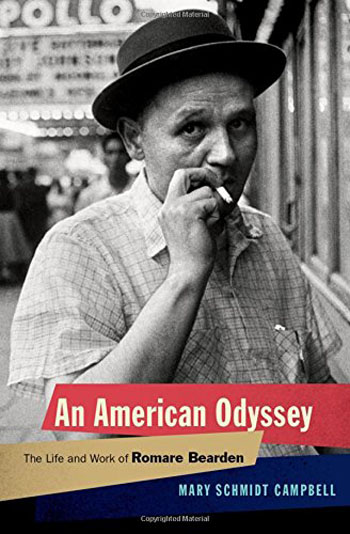

AN AMERICAN ODYSSEY: THE LIFE AND WORK OF ROMARE BEARDEN

By Mary Schmidt Campbell

Oxford University

Press. 443 pages. £22.99.

ISBN 978-0-19-505909-0

Reviewed by Jim Burns

It was never going to be easy for a black painter to make his way in

the American art world. Even if he displayed a natural talent for

drawing he would have found it difficult to obtain any formal

training, and in due course acceptance by commercial galleries and

public art institutions. Romare Bearden’s life is a story of a

struggle to survive as an artist in a hostile or at best, an

indifferent society. It raises the question: “Was he an artist, a

black artist, or an artist who happened to be black?”

Bearden was born into a middle-class black family in September,

1911. He grew up in what is described as a “privileged world”. His

great-grandfather, Henry Kennedy, was a “businessman and property

owner……and part of a small circle of black families who thrived in

Charlotte

(North Carolina)

from the end of the nineteenth century to the early years of the

twentieth”. Mary

Schmidt Campbell says that “Though Charlotte was progressive, it was

still mostly segregated”.

Despite some black families being able to succeed to a degree,

racial tensions still affected what they could do. Voting rights

were limited, for example, and there was always a threat of violence

should a black person be accused of breaking racial boundaries,

whether laid down in law or by custom. It was not surprising that

Romare Bearden’s parents decided to move to New York in 1915. They

eventually settled in Harlem.

Bearden’s mother, Bessye, was an activist: “She threw herself into

New York politics at a time of increased political

opportunity for black women”, and took courses in “public opinion,

city history, and civic organisation” at Columbia University.

She would clearly have a major influence on his life. as did New York itself. But

Campbell

points out that his experiences in

Pittsburgh, where he “lived twice during his

childhood” were equally formative. They gave him the opportunity to

take “a close look at the world of migrant steel workers”.

It was in New York, and especially

Harlem, that Bearden began to establish a reputation as

an artist. The 1930s were years when radicalism, of one kind or

another, often predominated in the arts. Artists, writers, and

musicians joined the Communist Party, or at least identified with

many of its concerns. Bearden’s paintings during this period were

influenced by the work of the Mexican muralists, Diego Rivera, David

Siqueiros, and José Orozco. As Campbell says: “All three

employed a style that allowed them to embrace modernism, adopt a

highly stylised realism, and portray unabashedly political and

social justice content”.

Around the same time, Bearden enrolled at the Art Students’ League

(ASL), where he encountered George Grosz, the German artist who had

fled

Europe when it was obvious that Hitler and his

followers would soon come to power. Grosz not only advised Bearden

in terms of his painting technique, he also directed his attention

to European painters like Brueghel, Goya, Daumier, and Käthe

Kollwitz, all of them with a high degree of social commentary in

their work.

Bearden may have had some minor success in

Harlem. contributing cover illustrations and cartoons to

black magazines like Crisis,

but it wasn’t sufficient to provide an income to live on. He got a

job as a caseworker for New York Social Services, something which he

continued to do for many years. It involved him in work that would

tie in with his social and artistic intentions.

Bearden had his first solo exhibition in 1940. Campbell says that : “The

works resemble the subject matter – if not the style – of social

realists like William Gropper, Jack Levine, and Ben Shahn, whose

subject-matter focused on victims of social and political

injustice”. But Bearden

was soon to dismay many of his admirers. He had become friendly with

Carl Holtz, an abstract painter, who took him to the “regular

gatherings” at the Greenwich Village

studio of “the avant-garde painter John Graham”. It was, according

to Campbell, “a focal point” for many of the

artists who would later become identified with abstract

expressionism, among them Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, and

Jackson Pollock.

Bearden’s new style, as it developed, in the immediate post-war

years, is described by

Campbell

in these words: “Colour, muted in the social realist paintings, is

exuberant in the literary abstractions

- sensual and full of light. Stylistically, Bearden makes use

of the abstract modernist vocabulary that mixes the syntax of cubism

– the two-dimensional overlapping planes of space, flattened,

shallow space that emphasises surface design instead of reproducing

a deep perspective –with a suppleness of line reminiscent of the

drawings of Matisse of the 1930s and 1940s”.

He still found it frustrating that he was often described as a

“black artist” instead of

simply being referred to as an “artist”, and it makes one

wonder whether or not his move towards abstraction wasn’t, in part,

at least, a way of diverting attention away from his ethnic origins.

Campbell

seems to suggest that it may have been at least a contributory

factor, and that he wanted to “make his work more universally

appealing”.

He was still employed as a caseworker, and that commitment, and the

necessity for him to care for his aging father, tended to limit his

activities among the New

York

art fraternity, despite having a successful exhibition at the Kootz

Gallery. In 1947 he was included in a

Paris

exhibition of American artists, though it doesn’t appear to have

been well received. One French critic was particularly harsh about

Bearden’s work and described it as “mediocre”. Bearden did visit

Paris in 1950 and met Picasso, Leger, and Brancusi. He also immersed

himself in the social life of the city and mixed in bars and clubs

with black expatriates.

By the early-1960s, Bearden’s abstractions were starting to show

signs of “a sort of lost momentum”. in the words of his dealer. But

he had been working on a series of collages, and when these were

displayed they immediately brought acclaim from critics. In a way

they returned to themes that referred to his experiences in earlier

years: “Scenes of the rural South, the cotton fields of

Mecklenburg County, trains that connected North and South, the

urban streets of Pittsburgh, and Harlem dominated the gallery”. The

New York Times described

Bearden’s work as “propagandist in the best sense”. In a way it was,

with Bearden speaking up for the black experience in

America. And doing so at a time

when increased assertiveness with regard to Civil Rights and similar

matters meant that to refer to a “black artist” was no longer a way

of ascribing his work to a lower status than that enjoyed by whites.

The Museum of Modern Art gave Bearden a retrospective show in the

early-1970s, though

Campbell

points out that “whole periods from Bearden’s body of work” were

eliminated. His political cartoons from the Depression, the literary

abstractions from the 1940s, and the “large non-objective oils from

the late-1950s and early-1960s” were curiously missing. Was this

Bearden’s choice, or one imposed on him by the gallery?

Campbell

has no answer, and she mentions that all the paintings on display

“were scenes of black life”. Did Bearden simply want to forget about

a time when he didn’t care to be singled out as a black artist,

though that wouldn’t explain the absence of his 1930s political

cartoons? Or was it that MOMA wanted to emphasise the black aspect

in his work?

Bearden continued to be active, though a controversy regarding a

mural he had created for a hospital caused him to retire to the

small island of

St Martin in the Caribbean.

He had grown increasingly tired of the hectic nature of New York life and was anxious to find

somewhere he could work in peace. He died in 1988.

I’m conscious of having moved quickly through Bearden’s life and

work, and that I’ve completely overlooked his activities as a

writer. He contributed articles and reviews to numerous

publications, including exhibition catalogues, magazines, and

newspapers. Campbell

provides a detailed bibliography of them. I’m similarly conscious of

having quoted extensively from

Campbell’s description of Bearden’s work.

There is a simple explanation for this. I can’t recollect having

seen a single canvas by Romare Bearden, though I have come across

illustrations In one or two books. And there are some excellent

reproductions of his work in the publication under review. Are there

examples of his work in any British galleries? Even if one or two do

exist, I doubt that Bearden’s name will mean much to most people in

the United Kingdom. But Campbell has had the

opportunity to study Bearden’s paintings and can describe and

analyse them much better than I could.

An American Odyssey: The Life and Work of Romare Bearden

is a fascinating book, lovingly detailed and closely illustrating

how its subject had to struggle, both as an artist and as a black

person, to establish a place in the history of art in

America.

|