|

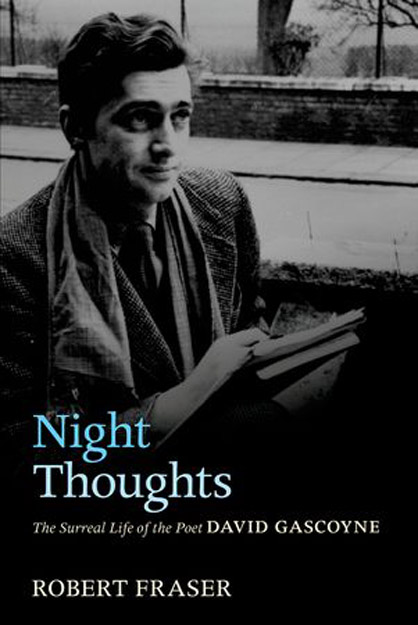

NIGHT THOUGHTS: THE SURREAL LIFE OF THE POET DAVID GASCOYNE

by Robert Fraser

Reviewed by Jim Burns

Gascoyne was born in 1916 and grew up in a household dominated by women. Robert Fraser says that: "In the longer term, an emotional and practical dependence on forceful middle-aged women became a pattern that would remain constant in him throughout his life." Intelligent and sensitive, he was a member of the choir school at Salisbury Cathedral, wrote his first poem when he was thirteen, and in 1931 met Alida Klemantaski, the estranged wife of Harold Monro, a minor poet and owner of the Poetry Bookshop. She ran readings at the shop and Gascoyne was taken to them so he could listen to and meet a variety of the poets then active in London. Klemantaski also arranged for Gascoyne to have access to the British Museum reading room. He had never been an attentive pupil at any school, preferring to follow his own concerns and ignoring what didn't interest him. Arthur Symons's The Symbolist Movement in Literature introduced him to Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Gerard de Nerval. And the bookshops along Charing Cross Road brought magazines like transition to his attention. All this was exciting but his school work suffered. The Headmaster told his parents that it was a waste of time keeping him at school as he would never pass the required exams, nor would he be suitable for the Sixth Form. As Fraser puts it: "Thus it was that, three months shy of his sixteenth birthday, David Gascoyne completed his formal education." He may have been a failure by the standards employed by mediocre schools, but he was educating himself. His first book of poems was published in 1932 and a novel in 1933. His early poems showed some influence of Imagism and, according to Fraser, "One of the main themes of the collection was the stranglehold of the familiar, and the desire to loosen its grip. Already, claustrophobia is a recognisable Gascoyian theme." But he was trying to get away from the familiar by broadening his reading. Fraser says that he "discovered an intriguing number of the bi-lingual magazine, This Quarter....a surrealist special - and it contained contributions by André Breton, Paul Eluard, and Rene Crevel, alongside artwork by Marcel Duchamp, Dali, and others." Inspired by what he read Gascoyne acquired more surrealist publications. The Poetry Bookshop had closed when Harold Monro died, but David Archer's shop in Parton Street was the gathering place for young poets and their readers. Archer is, as Fraser points out, "one of the unsung heroes of mid-twentieth century British verse," and little has been written about him. He came from a reasonably well-to-do family and graduated from Cambridge in 1932, and Fraser says that his family background and education "produced a leftward-leaning young man of slightly bumbling benevolence and eclectically radical tastes." Archer used most of the "small fortune" he inherited from his father to rent a building in Bloomsbury which he used for his bookshop and for accommodating various impoverished poets. His shop was a meeting place for editors and writers, and many "of the most innovative magazines of the period started life there." People like Archer rarely get the attention they deserve when literary histories are written, but without them it's more than likely that many poets would struggle to get into print. There is some information about him in Robert Fraser's biography of George Barker, The Chameleon Poet (Cape, 2001), where it's documented that Archer came to a sad end. Never careful with money he eventually used up his inheritance and fell on hard times. A trust fund was set up for him but he failed to use that properly and had to resort to scrounging from old friends around Soho. He lived in a Salvation Army hostel and died, a suicide, in 1971. It was in David Archer's bookshop that Gascoyne met George Barker, Geoffrey Grigson (editor of New Verse) and others, but his thoughts were turning increasingly to Paris. When he got there in 1933 he was soon mixing with writers and artists, including Max Ernst who introduced him to members of the surrealist group. When he returned to England he was determined to establish himself as a leading exponent of surrealism. He published poems in New Verse and New English Weekly which pointed to his credentials as a surrealist poet, and met Roger Roughton, another now mostly forgotten figure of the period and, like David Archer, destined to end his life as a suicide. Roughton always struck me as one of the more entertaining British surrealist poets, despite what appears to have been a slim output. I doubt that his poetry is widely known, though examples of it can be found in Poetry of the Thirties, edited by Robin Skelton (Penguin, 1964) and English and American Surrealist Poetry, edited by Edward B.Germain (Penguin, 1978). Roughton's main claim to being remembered is probably his editorship of Contemporary Poetry and Prose which ran for ten issues in 1936/37, and published many of the British surrealists. Like so many writers, Roughton joined the Communist Party, but became disillusioned by the failure of any sort of rapport between surrealism and communism to take place. The Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939 appears to have been the final nail in the coffin of his beliefs. He moved to Dublin and gassed himself in 1941. Gascoyne had been appointed art critic for New English Weekly, dismissing the Pre-Raphaelites as abominable, describing Turner as "a man of colossal bad taste, who sometimes painted great pictures as if by accident," and mocking Ben Nicholson's geometric abstractions. But his heart was in Paris and correspondence with Paul Eluard convinced him that he needed to visit the city again. He persuaded a publisher to give him a contract to write a short survey of surrealism. He also prepared the First English Surrealist Manifesto, noting that, in May 1935, "the whole of England - orchestrated by the capitalist press - is preparing for an hysterical frenzy of the most futile and dispiriting kind: the Silver Jubilee." The Manifesto also spoke in favour of "the proletarian revolution" and "the historic materialism of Marx, Engels, and Lenin," and came out against "humanism, liberalism, idealism, anarchist individualism." With the Manifesto in his luggage he headed for Paris, where it was published in the June 1935 issue of Cahiers d'Art. Gascoyne knew how to make the right gesture at the right time and in the right place. When he returned from Paris he had the material for his book. A Short Survey of Surrealism was published in late-1935 and largely attracted positive attention. As Fraser says: "Though the subject was surrealism, its mode of address and the organisation of its material were not in the least surreal." While writing this review I pulled a copy of the December 1935 New Verse from my bookshelves. Gascoyne's surrealist-sounding poem, "The Truth is Blind" is in it, along with a short review by him of books by Hugh Sykes Davies and Paul Eluard. There is also a review of A Short Survey of Surrealism by Charles Madge, and it's interesting to see what he says. He does acknowledge that the book is "really admirable," but notes that: "Surrealism is now in its academic period - the period of explanation and anthologies - the wider public. While we are young our energy is intense; when we are older our scholarship will be profound." Gascoyne also put together another collection of poems which David Archer published in his Parton Press series, alongside books by George Barker and Dylan Thomas. Man's Life Is This Meat was firmly surrealist in tone and Fraser describes the poems as "very much of their time." He also says that, in later years, Gascoyne "would evince some reluctance to have them collected, embarrassed to have his name automatically associated with a fad of his early youth." And, analysing some of the poems, he draws attention to the fact that not all of them slot easily into a distinctly surrealist style. They seem to find Gascoyne torn between a need to draw attention to his involvement with surrealism and a desire to express himself as an individual. There is, Fraser claims, "a persistently introspective and far more English-feeling, mood of solipsistic stillness" present that pulls away from the deliberate disorientation of the more-strident poems. Involvements with the now-legendary surrealist exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries in London and with the Communist Party followed. And Gascoyne went to Barcelona with Roland and Valentine Penrose, though he seems to have had some naive ideas about the situation there. The Penroses were representing the Independent Labour Party, an organisation that identified with the Partido Obrera de Unificacion Marxista (POUM) which was, in the eyes of the Communist Party, a Trotskyite organisation. Gascoyne was given a job translating news communiqués into English and reading them out on the radio. It didn't take him long to recognise what the political situation in the Republican part of Spain was really like. In his journal he noted: "I came to find out that the Communists hated the Anarchists and the POUM much more than they hated the Fascists." And he claimed that this was the beginning of his disillusionment with communism as a possible answer to the evils of capitalism. Involvements with the left-wing Artists' International Association and Mass Observation followed his return to London, and a friendship with the French writer Benjamin Fondane who viewed the surrealists as "a pack of deluded megalomaniacs" helped to re-enforce his observations of the movement's tendency to split under the pressure from the competing egos. When he visited Paris in 1937 he largely avoided the surrealists and mixed with non-aligned French writers and intellectuals and with expatriates like Henry Miller and Lawrence Durrell. He spent some time in Grez-sur-Loing which had functioned as an artists' colony since the 1880s. It was during his stay there that he started dabbling with drugs, initially opium. In what was to become something of a pattern he was rescued from the embarrassment of not being able to pay his hotel bill by the arrival of his mother and a friend. It's hard not to think that Gascoyne always depended on someone coming along to settle a bill or provide accommodation for him and that he assumed it would most likely be a woman. Benzedrine was soon a drug that he took to, partly because it was then available to purchase over the counter in the form of inhalers. He started using it to ease the pain from his teeth, which were in poor condition, and help with the catarrh he suffered from. Rejected for service in the armed forces he joined ENSA and toured as an actor, usually in minor parts. His benzedrine use increased as he cracked open the inhalers, extracted the benzedrine-soaked pad, and dropped it into a warm drink. Stress, irregular eating, and the benzedrine combined to give him stomach ulcers and he was hospitalised in 1943, though he discharged himself after a few weeks. He stayed with the artists Lucien Freud and John Craxton for a few more weeks, moved on to George Barker and Elizabeth Smart, and continued to use amphetamines which caused him to hallucinate. Fraser points to the intensity of the poetry he was writing at the time and wonders how much of it was due to the seizures and how much stemmed from his increasing religious convictions: "His poems were becoming more mystical, close in mood to Jouve's redemptive Catholicism with its images of hope swelling out of the darkness, despair sprouting wings." Pierre Jean Jouve was a Parisian poet and novelist whose salon Gascoyne had attended and whose wife, a trained psychiatrist, had helped the English poet . The post-war years were difficult ones for Gascoyne. His mental state was fragile, he had problems coming to terms with his homosexual leanings, his financial situation was precarious, and he was heavily addicted to amphetamines. Needless to say, the latest in the line of strong-minded women stepped in to provide accommodation and encourage him, though the relationship wasn't an easy one. And Gascoyne had moved away from surrealism and was beginning to act as an "advocate" for existentialism. He compiled "A Little Anthology of Existential Thought" for New Road, a hardback journal published by Grey Walls Press. Its general editor was Charles Wrey Gardiner, who Fraser describes as "a solemn and lecherous weasel of a man." He had edited the well-regarded Poetry Quarterly for a number of years, and a kinder view of him can be found in Derek Stanford's Inside the Forties (Sidgwick & Jackson, 1977). Wrey Gardiner's autobiographies, such as The Dark Thorn (Grey Walls Press, 1946) and The Flowering Moment (Grey Walls Press, 1949) are worth looking at, though their effusive style might not suit contemporary tastes. Like David Archer and Roger Roughton, Wrey Gardiner is one of those people who ought to be acknowledged when the poetry of the Thirties and Forties is written about. A trip to Paris once more found Gascoyne with an unpaid hotel bill, but as Fraser relates: "Enter, therefore, the seventh of Gascoyne's strong-minded middle-aged benefactresses," who rescued him, found him another room, and fed him. A similar situation occurred when he was in Venice on a travel bursary and once more defaulted on his hotel bill. He quickly sent some poems to Botteghe Oscure, a publication edited by the elderly and wealthy Princess Marguerite Gaetani and she promptly mailed a cheque so he could settle his debts. He also contacted Peggy Guggenheim, who lived in Venice, and managed to get an invitation to stay with her. I've got to admit that, reading about Gascoyne's life, I can't help being impressed by the way in which he always managed to find someone who would help him. Kathleen Raine once said that he "had lived for years by taking money from people who could afford to give it to him and many who could not”. And when asked if he was capable of holding down even the most basic job, she replied, "no, someone will always have to look after him." Curiously, when Raine was awarded the 1953 Annual Arts Council Prize for Poetry she gave some of the money to Gascoyne who used it for a trip to Paris. In England the mood of the poetry world was changing and the Movement poets were coming to the fore. Fraser quotes Charles Tomlinson referring to "Middlebrow" poets with "parochialism, irony, and a distrust of rhetorical thought and expression" dominating. Meanwhile, Gascoyne, though moving from address to address in Paris, was sufficiently organised to compile a programme about French cabaret singers for the BBC Third Programme which, when it was created in 1946, was designed to be a "vehicle for serious thought, debate, and music." It's a personal viewpoint but it struck me that we lost something very valuable when it was changed to Radio 3 and music became its main reason for its existence. On his return to England after an extended stay at the home of the wealthy Meraud Guevara, Gascoyne lived with his parents or with Elizabeth Smart who had separated from George Barker and was struggling to support four children but managed to find space for him in her flat. In 1959 he was involved in the founding of a new magazine, simply called X, which was designed to provide an alternative to the Movement poets. It didn't last very long - seven issues in three years - but as An Anthology from X (Oxford University Press, 1988) shows, it had a distinctive voice and gave space to mavericks like Brian Higgins and Cliff Ashby, as well as to Gascoyne, Barker, and others. It was around the time that X. folded that Robin Skelton edited Poetry of the Thirties and gave ample space to Gascoyne's more-surrealist inclined poems. His mental condition was precarious and he was arrested in Paris after trying to gain access to the Elysée Palace so that he could contact General De Gaulle. He told the police that he wished to speak to the French President about the "imminent apocalypse, of which he alone was apprised." After some weeks in an asylum he was allowed to return to England provided he lived with his mother on the Isle of Wight. He soon telephoned 10 Downing Street and asked to speak to Mary Wilson, the then Prime Minister's wife, who was herself a poet. According to Fraser he wanted to tell her that "Theocracy is the only humanly possible form of democracy," and that God, the Royal Family, and Harold Wilson, with help from Gascoyne, should be able to deal with the forthcoming Apocalypse. Given a polite brush-off by Mary Wilson's secretary he next attempted to get into Buckingham Palace so he could talk to the Queen. As with his attempt to see De Gaulle he was detained and sent to a psychiatric hospital. When his mother died and he was alone in the house on the Isle of Wight, he lapsed into what Fraser describes as "a state of complete physical and mental dereliction." He was placed in Whitecroft Hospital and it was there that his life took a turn for the better, thanks again to a kind lady. Judy Lewis visited Whitecroft as a volunteer and ran weekly poetry sessions at one of which she read out "a difficult poem by a man called David Gascoyne." When she'd finished a "tall, sad-looking man" said "I wrote that poem. I'm David Gascoyne," to which she replied, "Yes, dear, I'm sure you are," and moved on. It was only later that she realised that he really was David Gascoyne. By 1973 he had "shrunk into a chronic mental case cooped up in a provincial hospital on an obscure island, and assumed by professional carers and family alike to be incurable." With her assistance he started a slow climb back to some form of normality and began to appear at readings. He was also consulted by academics and students as an authority on surrealism. He travelled to France and the United States, and much of his work, including journals from the 1930s, was published by the Enitharmon Press. Interest in him revived, though Fraser says that he was "an object of curiosity ranging from the appreciative to the merely impertinent." Gascoyne died in a nursing home in 2001. Robert Fraser has written a well-researched biography of David Gascoyne which, as well as honestly following the ups and downs of his life, tries to draw attention to his writing. There's always a danger that someone like Gascoyne may be more read about than read, though I think there may be sufficient evidence to show that the best of his poetry can still attract readers. Enitharmon Press, to their credit, have kept a large proportion of his work in print. He may have been a difficult man to know at times, but David Gascoyne has a sure place in Twentieth Century poetry.

|