|

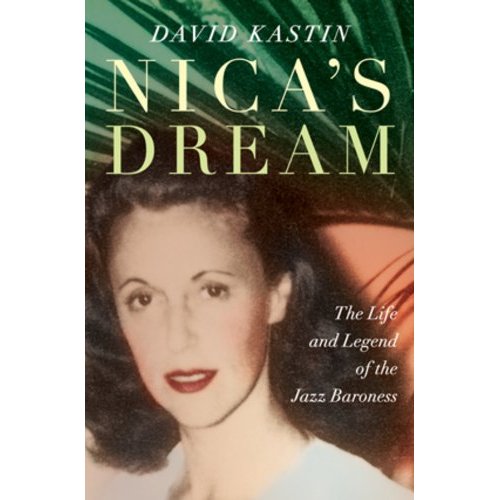

NICA'S DREAM: THE LIFE AND LEGEND OF THE JAZZ BARONESS Reviewed by Jim Burns

When Charlie Parker died in 1955 the New York tabloids had a field day. "Bop King dies in Heiress' Flat" shouted one of the headlines and details followed of how Parker, just prior to his death, had made his way to the "swank 5th Avenue apartment" of Baroness Kathleen Annie Pannonica Rothschild de Koenigswarter . It was a story likely to attract attention as it mixed allusions to race, class, jazz, sex and drugs in a manner that readers at the time would have seen as convincing proof that their suspicions about the subversive nature of jazz, and especially bebop, were justified. But who was Pannonica Rothschild (known as "Nica") and how was it that she knew someone like Parker? She was a member of the English branch of the Rothschild family and had been born in 1913 to parents who were obviously wealthy but who didn't just limit their activities to making money and maintaining large estates. Her father had a keen interest in the natural sciences and, according to David Kastin, is now looked on as "one of the pioneers of the modern conservation movement." He was an expert on fleas and amassed a collection of 30,000 specimens and published 150 scientific papers. Her mother had been a national tennis champion in Hungary, knew several languages, read Proust, and dabbled in politics. Nica also had an uncle who, like her father, was interested in the natural world. He was something of an eccentric and had a private zoo that included zebras, kangaroos, emus, and other species. Kastin says that the scholarly articles he published "established Walter Rothschild as one of the leading zoologists of his age." Nica's father still had to play a part in running the Rothschild bank even if his heart was with his other interests, and he suffered from bouts of depression and committed suicide in 1923. Her mother took over running the properties they owned and looking after the family finances. Nica's brother, Victor, had a traditional education, going to Harrow and Trinity College, but she was educated at home and had to conform to what Kastin describes as "stringently enforced schedules." The facts of her upbringing are interesting in terms of their possible effect on her later behaviour. Victor was a talented amateur pianist and was destined to lead a varied life. Kastin describes him as: "a research director of the Cambridge zoology department, a member of MI5 (the British secret service), Winston Churchill's personal envoy to President Roosevelt, a senior executive at Shell Oil, the chairman of N.M. Rothschild & Sons, the head of Britain's Central Policy Review Staff (a.k.a. the Think Tank), and the suspected 'fifth man' in the clique of Communist sympathisers known as the Cambridge spies." His interest in the piano had led him to jazz and friendship with the noted pianist, Teddy Wilson. It was Victor who first introduced Nica to jazz. Her education had been widened when she spent a year in Paris in the late 1920s and then toured Europe. Back home she mixed with other debutantes, frequented London night-clubs, and indulged her liking for fast cars. A London musician got her interested in flying and by the time she was twenty-one she had her own plane. A trip to France brought her into contact with Baron Jules de Koenigswarter and, after a quick romance, they were married in New York in 1935. A couple of children soon followed. When war broke out in 1939 Nica and the children were in France but she was told by her husband to go to England and then to America where they would be helped by the Guggenheims, "another of the great Jewish financial aristocracies." After ensuring that the children would be looked after Nica headed for North Africa where her husband, a supporter of De Gaulle, had joined up with Free French forces. She worked as a translator and decoder and later drove ambulances in Italy. After the war the Baron became part of the new French government and had diplomatic posts in Norway and Mexico. It's probable that, by 1949, the marriage was unstable, with Nica searching for something that would add meaning to her life. The Baron was contemptuous of her liking for jazz and she started visiting New York where she renewed her acquaintanceship with Teddy Wilson and met other musicians. In 1951 as she made her way to the airport to return to Mexico she called to see Wilson who insisted that she listen to a recording of Thelonious Monk's Round Midnight. Kastin quotes from an interview in which she recalled what happened: "I couldn't believe my ears. I had never heard anything remotely like it. I made him play it to me twenty times in a row. Round Midnight affected me like nothing else I ever heard." And he adds that she missed her flight and extended her stay in New York by a couple of weeks so that she could experience more of Monk's work. By 1953 Nica was living permanently in New York and had separated from her husband. When the jazz writer, Nat Hentoff, asked her about breaking with the Baron and her children, as well as virtually giving up the kind of social status and way of life that many would envy in order to mix with mostly black and often impecunious jazz musicians, she responded by affirming her love of the music: "It's everything that really matters, everything worth digging. It's a desire for freedom. And in all my life, I've never known any people who warmed me as much by their friendship as the jazz musicians I've come to know." Throughout his account of Nica's life Kastin breaks off to offer his analysis of events and developments in the arts. To set the scene for her arrival in New York he outlines how bebop came about, what the Beat writers aimed for in their poems and novels, and where Jackson Pollock and other abstract expressionist painters were heading in their search for new forms. It's a narrative that holds fairly closely to what has become a fairly standard history of artistic changes post-1945, with a so-called "culture of spontaneity" taking precedence over other areas of activity. To be fair to Kastin he doesn't go overboard for this version of events and he notes that the musicians, artists, and writers he refers to weren't always "promoting the same aesthetic agenda." It's a sensible qualification to make because generalisations about movements in art or music or literature can often be seen as faulty when looked at in detail. As Nica involved herself with the New York jazz community she did meet with a degree of suspicion on the part of some musicians. They wondered what she wanted from them, and inevitably in what tended to be a male-dominated environment it was suggested that she was sleeping with this or that jazzman. Kastin says that gossip columnists like the notorious Walter Winchell commented on her liking for being in the company of black musicians, and society types sneered at her taste for visiting run-down places where bebop could be heard. Kastin doesn't refer to it in detail but in the early-1950s bebop was considered subversive, with its practitioners mostly junkies. This was when the McCarthyite hysteria was at its height and not only communists were thought of as threats to the American way of life. It has to be accepted, though, that the use of drugs, particularly heroin, had spiralled in the late-1940s and early-1950s, and that it was a major problem among the beboppers. Kastin points out that the Mafia became heavily involved in developing markets for heroin once the supply lines opened up again following the end of the Second World War, and he suggests that black communities were targeted most of all. But he gives other reasons for the increased use of heroin: "Heroin's ascendancy during the bebop movement can also be seen as both a symptom of the bebopper's marginalised role in the pop music mainstream and an emblem of hipness worn (along with berets, shades, and goatees) by a generation of black jazz modernists who were challenging the vestiges of minstrelsy they associated with their big-band predecessors. For their white cohorts, the drug became a way of symbolically connecting to their musical heroes." Kastin talks about the drugs problem among the New York modernists because Nica, like anyone observing the musicians, couldn't help being aware of it. And some criticism was levelled at her for the way in which she appeared to respond to the situation. There were suggestions that she should have done more to persuade people to stop using heroin, and a fictional character clearly based on her in a short story by Julio Cortazor appears to obtain drugs for an addicted saxophonist. She was, perhaps, sometimes over-tolerant of the behaviour of certain musicians, and tended to excuse their personal failings by referring to the music they produced, but experience taught her to be wary. Discussing addicted musicians and their problems she said: "I used to think I could help, but no one person can. They have to do it alone. I had to find out for myself that one has to stay away from them. Addiction makes them too ignoble, and you can't be safe around them." It is known that she helped a great many musicians by giving them money, buying food for their families, and sorting out the chaos surrounding the cabaret cards they needed in order to work in clubs in New York. A criminal conviction meant that a musician could be denied a card. This was particularly disastrous for blacks who often couldn't find alternative employment in the recording studios and elsewhere. Not only musicians were affected and the card system applied to anyone working in a club as a waiter, cook, or whatever. Kastin raises the interesting point that when it was first introduced the idea was to apply some form of control to unions, such as the one organised among waiters, which were said to be communist dominated. Its most notorious use, however, seems to have been when musicians, singers, and other performers were involved. Needless to say, it was wide open to abuse by the police and a payment into the right pocket often meant that a card would be issued even if the person concerned had a conviction or two. I mentioned earlier that Charlie Parker died in Nica's suite at the Stanhope Hotel in New York, and that, along with complaints about noise as she entertained various musicians, led to her being asked to leave, a process repeated when she moved to the Bolivar Hotel. Parker's death and the accompanying publicity also caused her husband to sue for divorce and custody of the children. And the Rothschild family, with a few exceptions, closed ranks on her. They may have been rich and famous but courting publicity in the manner that contemporary celebrities do was not part of their thinking. For them, the only time your name should appear in the press was when you were born and when you died. Nica's life seemed to contradict much of what they had been taught to believe was the correct way to behave. Her links to Parker were, in fact, relatively limited when compared to her devotion to Thelonious Monk. A major part of Kastin's book deals with her relationship to this enigmatic character. There's no doubt that Monk had problems and Kastin says that he inherited bi-polar disorder from his father. But sustained use of drugs over many years also affected his mental condition. At various stages he was diagnosed as schizophrenic, suffering from a chemical imbalance, and with manic tendencies. He was given shock treatment and subjected to psychotherapy which verged on the farcical. Nica's endeavours on his behalf were, at times, almost heroic, especially as he was responsible for her being evicted from a third hotel. In due course it was agreed that having her own place was the best option, and with the help of her brother she bought a large house that had previously been owned by Joseph von Sternberg. It soon became known as The Cathouse due to Nica's fondness for cats, and it was also open house for any number of jazz musicians. Thelonious Monk's life after the early-1970s was a near-tragedy. He spent time in a private clinic, with the fees paid by Nica, and he left his wife and settled in The Cathouse, though not because of any sexual liaison between Nica and him. He simply needed to get away from the domestic arrangements that applied at home. It was during this period that he virtually stopped playing the piano and started to retreat into near-silence. He died in 1982. Nica was by that time in her late-sixties, but she continued to befriend musicians and visit the few remaining jazz clubs in New York and she was contacted by some younger members of the Rothschild family who had become intrigued by hearing about her and her adventures among the jazz fraternity. She died in 1988. Nica had written a memoir, but it has never been published and the manuscript is in the possession of the Rothschild family along with numerous tape recordings she made of the musicians who stayed at the Cathouse. Kastin says that her five children continue to reject requests for interviews about their mother, and even refused to help a cousin, Hannah, when she made a documentary about Nica. Another young relative, Nadine, was luckier when she wanted to publish Three Wishes, a collection of Nica's photos accompanying the three wishes that she'd invited her musician friends to make. It's an intriguing book and I can't resist quoting a couple of the wishes made by the bebop pianist Barry Harris: "A room with a Steinway and a good record player, where I can be alone with all the Charlie Parker and Bud Powell records," and "The end of all soul, funk, and rock'n'roll jazz." The reluctance of the Rothschilds to give interviews, and a certain amount of reticence on Nica's part when talking about her family background and life, has meant that David Kastin has written a book that is as much about New York and its bebop musicians as it is about her. Perhaps that's the way it should be because her devotion to the music and the people who played it was legendary. There are a few minor errors. Wardell Gray is called Grey, and Jackson Pollock somehow comes out as Pollack several times. When Kastin discusses the Julio Cortazor story, "The Pursuer," I mentioned, he says that it's "set in New York's 1950s jazz underground," but it's actually located in Paris. A final point. Several musicians, including Monk, named compositions for Nica ("Nica's Dream" is one of them, as is "Pannonica") and there is currently a CD available which brings together recordings by Monk, Doug Watkins, Kenny Drew, Gigi Gryce, and others, paying tribute to her. Nica; The Jazz Baroness is available on Saga 531 093-0.

|