|

ART ALONG THE SOUTH COAST

JOHN NASH : THE LANDSCAPE OF LOVE AND SOLACE

Towner Gallery, Eastbourne, 18th May, 2021 to 26th

September, 2021

SEASIDE MODERN : ART AND LIFE ON THE BEACH

Hastings Contemporary, Hastings, 27th May, 2021 to 31st

October, 2021

DOWN FROM LONDON : SPENCER GORE AND FRIENDS

Brighton Museum & Art Gallery, Brighton, 18th May, 2021

to December, 2021

Reviewed by Jim Burns

The main attraction on the South Coast at the moment is undoubtedly

the big exhibition of the work of John Nash. But this should not be

allowed to draw attention away from two other fascinating shows

which, in fact, can be seen to have links of one kind or another to

the Nash. What we are dealing with in all three is primarily English

art (I’m deliberately using “English” as opposed to “British”) in

roughly the first fifty years of the Twentieth century.

Nash did continue painting into the 1970s, though his key

works had probably been produced earlier.

Born in 1893 he showed an early aptitude for drawing, but never had

any formal training, unlike his older brother, Paul, who went on to

establish a reputation as a well-known British artist. It has often

been said that John was always overshadowed by Paul as the latter

was acclaimed as a war artist and, in the 1930s, played a part in

the British Surrealist movement. John himself had been a war artist

before the end of the First World War, but prior to that had been an

infantryman in the trenches. He had directly experienced what war

was really like. His painting, “Over the Top”, has nothing heroic

about it. The soldiers walking wearily towards the enemy seem almost

resigned to their fate.

Nash had been active before 1914 and a member of the New English Art

Club. Among his contemporaries were Harold Gilman, Charles Ginner,

Robert Bevan, and Spencer Gore, and one or two of them have a corner

in the exhibition to indicate their involvement in the Cumberland

Market Group, to which Nash belonged for a short period. But I have

the feeling that groups and movements were never really to his

taste. He seems to have gone his own way most of the time, though he

had individual friends, such as Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden,

who shared his liking for rural life and landscapes. There are quite

a few Nash landscapes to be seen in Eastbourne, and they are all a

delight to look at, though I did occasionally feel that a blandness

of composition sometimes seemed to creep in.

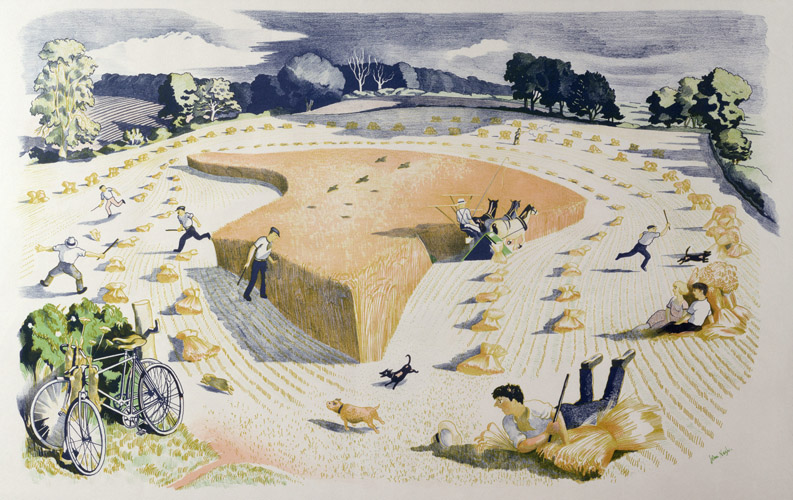

What I did find especially impressive were Nash’s woodcut engravings

and his work as a botanical artist. He illustrated issues of

The Countryman and

provided colour lithographs for various books.

His drawings point to his

extensive knowledge of flowers and plants. His work was varied,

however, and he would sometimes take a break from country matters

and paint a dockside scene in Colchester or somewhere similar. But

he was a countryman at heart and the exhibition emphasises this

fact. Nash may not have been an innovator, nor did he paint any

truly major pictures, but he was consistently skilled at what he

did. And this well-mounted and informatively-documented exhibition –

the largest in over fifty years - is a fine tribute to an artist who

deserves to be remembered.

John Nash isn’t represented in the exhibition at the Hastings

Contemporary, but brother Paul is there several times. The general

theme is how, in the interwar years, the English took to the seaside

for their day trips and holidays, and artists likewise decided that

what could be seen on the shoreline was suitable for painting. There

are photographs of families and it’s noticeable how formally dressed

they are for relaxing on the sands. Advertising indicates how rail

companies sought to encourage people to travel to the seaside. And

artists like Fortunino Matania and Laura Knight were employed to

create designs for posters that would point to the excitement and

glamour to be found in Southport and elsewhere. Matania’s version of

Southport suggests that it’s all sunshine and pretty girls in

bathing suits. It’s a different world to the one provided by L.S.

Lowry’s July, the Seaside.

Ordinary mums and dads with kids in tow or building sandcastles seem

to be prominent. And, for another version of holiday fun, there’s a

delightful William Roberts’ painting with his familiar tubular

figures cavorting on the beach.

Other artists were busy capturing different aspects of the coast.

Barbara Hepworth’s abstract sculpture and Eileen Agar’s surrealistic

photograph of a beached tree are examples of what the imagination

can do. Eric Ravilious and John Piper with a combination of colour

and form extend the realistic into the curious. There’s also a

suggestion of a darker side to the coast in John Minton’s pen and

ink drawing, On the Quay,

Cornwall, with a lone male figure posed by some small boats and

an odd-looking bird almost beneath his feet. One of the pleasures of

this exhibition is that some of the artists – Mary Adshead and Edgar

Ainsworth, for example - are relatively little-known. Ainsworth’s

pen and ink drawing of Blackpool in 1945 captures its crowded and

noisy good-humour.

Brighton, like Blackpool, attracted people out for a good time, but

the exhibition there isn’t concerned to register anything to do with

that fact. In 1913 Spencer Gore, a forward-looking young artist and

a member of the Camden Town Group, organised an

Exhibition of English

Post-Impressionists, Cubists and Others at the Brighton Public

Art Galleries. The current exhibition doesn’t attempt to recreate

the earlier one, but it does aim to commemorate it in some ways.

Gore’s friends from Camden Town– Harold Gilman, Robert Bevan,

Charles Ginner - are present, and just as he broke the rules in 1913

by including women (they weren’t allowed to be members of the Camden

Town Group), we can now see paintings by Sylvia Gosse, Thérèse

Lessor ,and one or two other women artists.

I have a great fondness for the Camden Town painters, and Charles

Ginner in particular. His precision is impressive (he trained as an

architect) but his paintings are not just displays of technique and

it never becomes overwhelming when combined with his astute handling

of colour. There is a fine balance in his work that enables it to

convince in a quiet way.

As for Gore himself, he tragically died at the early age of 36 as a

result of developing pneumonia due

to painting outdoors in bad weather. He had seemed destined

to become a leading modern painter, influenced by Cezanne and André

Derain,, and with encouragement from Walter Sickert, but has perhaps

often tended to be overlooked when people talk about the Camden Town

Group. It didn’t last long and it might have been interesting to see

what Gore would have done had he lived and gone on to different

things. Would he have joined with others to form a new group? It

seems that Wyndham Lewis spoke favourably about his work in the

Vorticist magazine, Blast,

but would Gore have moved that way rather than staying with the

largely domestic and urban concerns favoured by Sickert?

It’s a small exhibition in Brighton – around forty works on display

– but a very positive one in terms of illustrating how attractive

much Camden Town painting can be. It’s not that any of the artists

were great painters, but they were often very good ones. They had

absorbed lessons from France but at the same time maintained a clear

English sensibility when it came to subject-matter and how

best to represent it in paintings. I’ve noticed how any

exhibition of work by the Camden Town group, or the Cumberland

Market artists, and the Fitzroy group – the same people were in and

out of all of them – will usually attract a decent-sized crowd. It’s

understandable. With their often bright colours, and scenes of

streets and market-places, or interiors with figures in a variety of

situations, the paintings are pleasing to consider.

|