|

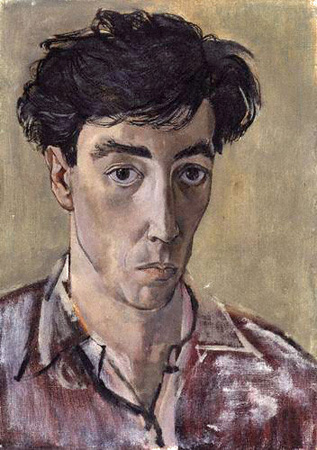

JOHN MINTON: A CENTENARY

An exhibition at the Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, 1st July to 1st October,

2017

JOHN MINTON: A CENTENARY

By Simon Martin and Frances Spalding

Pallant House Gallery. 128 pages. £24.95. ISBN 978-1-8698-2786-1

A DIFFERENT LIGHT: BRITISH NEO-ROMANTICISM

An exhibition at the Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, 10th June to 24th

September, 2017

JEAN COOKE: DELIGHT IN THINGS SEEN

An exhibition at the Jerwood Gallery, Hastings, 24th May to 10th

September, 2017

Reviewed by Jim Burns

Artists are sometimes remembered by the majority of people more for

their links to other painters and places than for their own work.

John Minton’s name crops up in all the books about

Soho

in the 1940s and 1950s, drinking alongside Francis Bacon and Lucian

Freud In the Colony Room, being photographed by John Deakin, and

tragically committing suicide at the age of 39. Jean Cooke was, for

many years, overshadowed by her husband, John Bratby, who abused her

in more ways than one, and was jealous of any sort of success she

had with her paintings. But it would be a pity if Minton and Cooke

were only known for their personal involvements with other artists.

Both had something of value to offer in their own right.

John Minton was born in 1917 into a middle-class family and in later

life was a trust beneficiary, so “was never dependent purely on his

art, and he could be remarkably generous to his friends”. He had a

good education, and in 1936 was awarded s scholarship at the St John’s Wood

Art School.

He exhibited at the Westheim Gallery in London

in 1938, and thanks to his private income he was able to spend

several months in

France

with Michael Ayrton. In 1939 he collaborated with Ayrton on designs

for a production of Dido and

Aeneas that was never realised.

The outbreak of war in 1939 found Minton at first attempting to

register as a conscientious objector, but then enrolling for service

in the army. He continued to exhibit and worked with Ayrton on

designing sets and costumes for John Gielgud’s

Macbeth at the Piccadilly

Theatre. He was discharged from the army on health grounds in 1943,

and for the next three years shared a studio with the Scottish

artists, Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde.

I don’t think it’s necessary to outline all of Minton’s activities

in the post-war period. He exhibited regularly here and there, and

contributed cover

illustrations to publications like

Penguin New Writing and

for numerous novels. The exhibition in

Chichester

includes examples of his work in this line. He also travelled to France and Spain. And taught at various

institutions, including the Royal College of Art. What also

impresses is the range of people, especially artists,

that Minton knew and mixed with. They included Lucian Freud,

Keith Vaughan, Francis Bacon, the two Roberts, Rodrigo Moynihan,

Richard Chopping, Denis Wirth-Miller, and many others. The

Soho

bohemia of the late-1940s and 1950s was, in many ways, his natural

habitat when he wasn’t teaching or painting.

Minton’s seeming gregariousness and love of drinking and dancing may

well have been signs of a basically insecure disposition that led to

his suicide in 1957. Minton was openly homosexual at a time when it

was a criminal offence and the police were actively attempting to

entrap men into committing acts that would lead to their arrest.

There is a dark painting in the exhibition that shows a figure

loitering in the shadows as if in anticipation of some sort of

assignation, or encounter, no matter how dangerous.

The material on show in Chichester

encompasses a broad sample of Minton’s work, from colourful

paintings, to some splendid pen and ink drawings, to illustrations

for magazines and books, and film posters. And it’s especially

encouraging to see that his skills as an illustrator are given their

fair share of attention. There may be a tendency, in certain

circles, at least, to relegate book and magazine covers, and other

forms of what some will consider tantamount to advertising matter,

to a lower category than canvases, but it strikes me as unfair if

that Is the case.

There is much to be gained from looking at an apt jacket design for

a novel, and Minton had a flair for such things. It may be that his

best-known book covers are those he did for some Elizabeth David

cook books, and that those for what are, in many cases, fairly

obscure and forgotten novels, are consequently destined to be

overlooked. But there are sufficient of them in the exhibition to

persuade a fair-minded observer that Minton excelled at illustrating

a variety of subjects.

With regard to his paintings, they often have an immediate impact

because of their bright colours, particularly when Minton travelled

to Corsica or

Jamaica. But there are also some

London

scenes from 1946/47 in which, the catalogue suggests, “the strong

colours suggest neither daytime nor night”. They certainly don’t

adhere to a popular notion of post-war

Britain

as a grey and dismal place, though it has been suggested that they

do point to a decline in the country’s fortunes, with its industrial

base shattered. The picturesque is ultimately going to take over

from the commercially busy. And the skies appear to indicate

impending storms.

By 1957 or so tastes in art were beginning to change. Abstraction

was coming to the fore and in 1956 the Tate staged a show of

American Abstract Expressionism.

Minton was strongly opposed to abstraction, and it could have

been that an awareness that his style of painting was being

overtaken and likely to go out of fashion, combined with his

alcoholism and his chaotic personal life, pushed him into suicide.

For a deeper consideration of Minton’s mental state at the time of

his death I’d recommend Frances Spalding’s

Dance till the Stars Come

Down: A Biography of John Minton (Hodder & Stoughton, 1991). It

could also be useful to read the chapter on Minton in Malcolm

Yorke’s The Spirit of Place:

Nine Neo-Romantic Artists and their Times (Constable, 1988).

Back in 1987, when I saw the exhibition,

A Paradise Lost: The

Neo-Romantic Imagination in

Britain

1935-55 at the Barbican, John Minton had a prominent place in

it. For obvious reasons he’s not included among the Neo-Romantic

artists like MacBryde, Colquhoun, John Craxton, John Piper, Paul

Nash, and several more, on show in Chichester. It’s instructive,

though, to have a look at their work in order to see the kind of

context Minton was operating in. In 1987 it was suggested that

Neo-Romanticism had been “repressed and edited out of the history of

British art and culture”, and it was true that abstraction and Pop

Art and other post-1960 movements had more or less consigned

Neo-Romanticism to, if not the dustbin, then the storage room of

history.

It’s good that recent years have seen the paintings being brought

out and put on display again. I’ve seen an exhibition of Colquhoun

and MacBryde in Edinburgh, another of Robin Ironside in

Chester, and earlier this year there was an exhibition,

The Romantic Impulse: British

Neo-Romantic Artists at Home & Abroad 1935-1959 at the

Osborne Samuel Gallery

in London.

An informative catalogue was published in connection with the

exhibition.

If Neo-Romanticism is “a difficult term to define”. and its

“boundaries and content” have more to do with “a spirit of place”

and an “impulse to convey a sense of Britishness”, then this might

be a useful time for looking again at the work of Minton, Craxton,

Leslie Hurry, Prunella Clough, and their contemporaries, not just to

set the historical record right, but also to highlight the work of

several imaginative artists. They can be looked on as members of a

loosely-defined group, but perhaps more as individuals with

characteristic, and sometimes similar, content (“the lyrical….the

mystical, the romantic, and the preoccupation with linear

rhythms….”) in their paintings.

Jean Cooke can’t be grouped with the Neo-Romantics, but she’s a

neglected figure and deserves to be recognised for her own work and

not just because she was at one time married to the roaring boy of

the British art world, John Bratby. Life with him wasn’t easy and he

wasn’t averse to painting over her canvases, and even damaging

something of hers that he didn’t approve of. Bratby was, of course,

the leading light of the so-called “kitchen-sink” school of artists,

and even when he allowed her to paint he tried to get her to adhere

to that style.

There is a 1958 painting by Jean Cooke in the Hastings exhibition, and

it is very much akin to what John Bratby was doing. It shows him

looking through an open window into the kitchen from outside. It has

all the acknowledged signs of a “kitchen-sink” canvas, the bottles

and packets, the glimpse of a sink. A later

portrait of Bratby has him white-bearded and looking rather glum.

Perhaps it was payback time for when he forced her act as his model

and, to suit the kitchen-sink image, usually made her appear

downtrodden and miserable, which she most likely was, anyway.

When she finally broke away from Bratby she left the kitchen sink

behind, and had a reasonably successful career under her own name.

The exhibition has some attractive nature scenes set in gardens and

woods, and one or two conventional but likeable portraits. Jean

Cooke wasn’t a major painter, but she could be an interesting one.

The critic Andrew Lambirth said: “A characteristic Cooke painting

takes the real world and views it from a slightly odd angle – as if

musingly with head on one side”. It’s an accurate description of her

approach to painting.

|