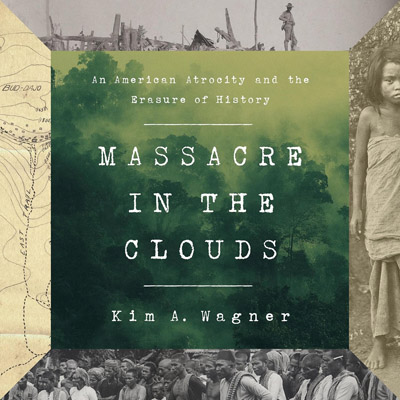

MASSACRE IN THE CLOUDS : AN AMERICAN ATROCITY AND THE ERASURE OF HISTORY

By Kim A. Wagner

Public Affairs. 352 pages. $35. ISBN 978-1-55417-0149-6

Reviewed by Jim Burns

In March, 1906 American soldiers worked their way up Bud Dajo, a mountain on

the island of Jolo, located in the southern part of the Philippines. Their

object was to attack a large concentration of Moros, a native people who

were looked on as “hostiles” by the authorities. But why were American

troops in action in the Philippines? It’s perhaps necessary to provide at

least a brief background to the events of 1906.

The United States went to war with Spain in 1898 largely over the question

of Cuba, then ruled by the Spanish. The war didn’t last long and the result

was that Spain left Cuba, and Puerto

Rico, Guam, and the Philippines (all previously Spanish territories) were

transferred to the Americans. The Filipinos had for some years been fighting

the Spanish in a war of independence, and initially saw the Americans as

liberators. They quickly realised that, in fact, they were now their new

rulers. Fighting then took place between the Filipinos and the Americans,

ending in 1902 with the defeat of the rebels. One area held out and that

was Jolo, where the Moros were the dominant people. They were

Muslims, whereas the rest of the Philippines was mainly Catholic. And the

Moros would have preferred to be independent of both the Catholic majority

and the Americans.

That’s a very quick summary of the situation in 1906, but it does perhaps

explain why the American army was taking action against the Moros who were

generally seen as bandits, pirates, and other categories of troublemakers

who refused to pay what was to them a form of poll tax. There had been

fighting between the two sides prior to 1906, but matters had come to a head

and a new governor, Major General Leonard Wood, was determined to inflict

what Kim Wagner refers to as a “key tenet of colonial warfare”, a “moral”

lesson. The Moros had to accept that the Americans always knew best and were

there to civilise them.

The United States was not alone in asserting this message – known as “the

white man’s burden” – and the examples Wagner mentions of “civilising

missions” by British, German, Belgian, and Dutch forces are striking. When

Kitchener and his Anglo-Egyptian army mowed down thousands of the Khalifa’s

ill-armed supporters at Omdurman in 1898 he was, presumably, teaching them

that “moral” lesson. Very few of Kitchener’s troops were killed or wounded.

European armies had artillery, machine guns and high-powered rifles. Native

forces were often armed with swords, spears, shields and sometimes a few old

guns.

A large body of Moros had retreated to Bud Dajo, a mountain with an extinct

volcano at its peak. There they had constructed a series of small forts,

with a defensive perimeter of trenches and fences around the crater, and

various barricades on the paths leading up the mountain. Dense jungle

surrounded it, and it was, seemingly, quite an impregnable position, or so

the Moros appeared to have thought. They had their wives and children with

them and had prepared for a siege by building up stocks of food.

The Americans, infantry and dismounted cavalry, with local guides and a

contingent of Philippine Constabulary to support them, eventually reached

the top of the mountain, though they suffered some casualties on the way.

They had managed to get a machine gun and three mountain guns into position

and between them they accounted for many of the deaths among the Moros.

Wagner refers to a Second-Lieutenant Mack who commanded a gun on the eastern

side of Bud Dajo: “Shrapnel was

typically used against enemy personnel and was designed to cause maximum

bodily injury. Mack’s gun fired

some 150 shrapnel shells on the Moros’ entrenchments”. A later report said,

“many dead... were found horribly mutilated with shrapnel fragments”.

The crater had offered a form of shelter until the shells started to

land among the people hiding there.

As for the machine gun, its use is illustrated by the following account from

an observer who watched as a large group of Moro women and children

appeared. The officers overseeing the machine gun “plainly saw these women

and children arrange themselves in line, and that they were unarmed

and that their action meant

surrender; but that after a few moments’ observation they turned the guns on

them and mowed them down to the very last one. Some after being shot down

once, struggled to their feet and were again shot down. They were afterwards

found in line with dead babies in their arms and not a weapon of any kind in

their possession”.

Wagner’s description of the assault on the Moro stronghold is quite detailed

and I’ve simply selected one or two points to highlight the one-sided nature

of the “battle”. As well as the machine gun and the mountain guns, there

were several hundred soldiers and constabulary armed with modern rifles and

revolvers able to maintain a

consistent fire on the Moros. It’s probable that around 1,000 Moros were

killed. A few women and children were captured. No men survived. Any wounded

found on the battlefield were finished off by the soldiers. That wasn’t

unusual in colonial warfare. Kitchener’s men had done the same after

Omdurman, and I recall reading that Zulu wounded at Rorke’s Drift were given

similar treatment. Casualties among the soldiers at

Bud Dajo were, according to General Wood, 18 dead and 59 wounded. He

didn’t include any dead or wounded Constabulary in his figures. It would

seem that three Constabulary died during the fighting.

When news of the defeat of the Moros reached America it was, on the whole,

received with acclaim. President Theodore Roosevelt (a personal friend of

General Wood) sent a message of congratulations in which he referred to a

“brilliant feat of arms”, and

newspapers generally praised what the army had done. The

Washington Post did say that the

“Battle of Mount Dajo was one of Extermination”. And there were some

exceptions among the general public, mostly among members of the

Anti-Imperialist League, and Mark Twain described the fight as a

“slaughter”. But many Americans, if they were interested, most likely

believed that their army had acted well against “terrorists” and “savages”.

It was a small action in a distant country, and not much different from the

Indian wars that were within living memory. The Seventh Cavalry had taken

its revenge on the Sioux for “massacring” Custer and his men on the Little

Big Horn in 1876 by carrying out a real massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890

when the Indians were, according to the authorities, reluctant to give up

their traditional way of life. Wagner notes that some of the older officers

at Bud Dajo had served in campaigns against various Indian tribes. Campaigns

that can be seen as genocidal in intent : “Kill and scalp all, big and

little; nits make lice”, one officer was reported to have said. Many of his

soldiers quite happily did just that.

There were photographs taken on Bud Dajo, some during the fighting, others

in its aftermath. One in particular stands out and is reproduced in the

book. It shows a trench full of dead Moros, including women, with American

soldiers standing around and obviously aware that what they had done was

being recorded for posterity. When it began to circulate, along with other

photos, sometimes on postcards, there were attempts to suppress it.

General Wood even visited the photographer who’d taken the original

photo and “accidentally” dropped the glass negative and shattered it. He

assumed that it would limit further circulation, but there were already

prints made from the original, and the photographer managed to piece the

smashed negative together in usable form.

Wagner links what happened on Jolo not only to the genocide practised

against Indians in the United States, but also to “lessons derived from

European colonial warfare in Africa and Asia, which provided countless

precedents of punitive campaigns in which villages had been burned, crops

and livestock destroyed, and men, women, and children killed

indiscriminately”. It shouldn’t be

thought that Bud Dajo was an isolated example of the

methods used against the Moros, though it was the one with the

largest number of dead. In 1904 the Americans attacked the fort of a

Moro chief called Usap. They killed everyone inside (226 Moros

including women and children) at the cost of seven wounded soldiers. Some

years later, in 1913, General John J. Pershing attacked Moro warriors on a

mountain called Bud Bagsak :

“Although there were no women and children among the Moros at Bud Bagsak,

the disparity in casualties was no less striking than it had been at Bud

Dajo. Pershing’s forces suffered fourteen dead and twenty-five wounded,

whereas it was estimated that some four hundred Moros were killed”. The

Americans had all the usual modern armaments, including hand grenades.

Massacre in the Clouds

is an impressive book. Wagner’s research took him not only to libraries and

other establishments, but also to the Philippines and particularly to Jolo

despite warnings that it was not safe. The Moros were still fighting a war

against the rest of the Philippines in an effort to secure independence. I

doubt that many people in the West know too much about it, or about its

background in the Spanish occupation of the Philippines, the American

imperialist takeover, and the fighting at Bud Dajo and elsewhere. Kim Wagner

has provided a real service by bringing this history to our attention.