|

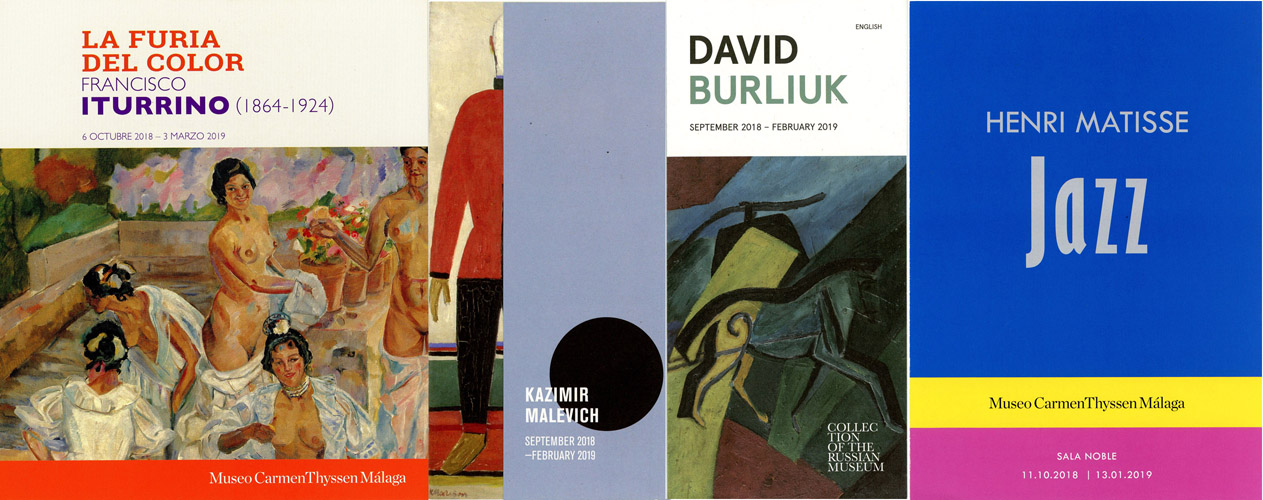

KAZIMIR MALEVICH.

DAVID BURLIUK

THE FURY OF COLOUR: FRANCISCO ITURRINO (1864-1924)

HENRI MATISSE: JAZZ

PICASSO’S SOUTH: ANDALUSIAN REFERENCES

The

But there was more to Malevich than that one iconic work, and the

exhibition follows him through his career as he touched on

Impressionism, Cézannism, and Futurism. His influence was profound,

not only in terms of the effect his paintings, but also because of

his positions within various artistic institutions. But that was a

role which may have led to him being suspected of “bourgeois

tendencies”, among other things, by the new breed of bureaucrats

determining what was acceptable as Stalin’s grip on power increased

and Socialist Realism became the dominant mode in art. Malevich was

imprisoned for a time in the early-1930s, bizarrely on a charge of

spying, and one wonders what might have happened to him had he not

died in 1935. There is some evidence discernible in his work from

the 1930s to indicate that he played down its experimental aspects

and adopted a less-controversial stance.

I doubt that David Burliuk is a familiar name, other than perhaps

among a few specialists in twentieth-century Russian art. He was

born in 1882, and has been called “the father of Russian Futurism”.

The

What is striking about Burliuk is that he seems to have involved

himself in almost every avant-garde artistic and literary movement

of his time, and he knew numerous painters and poets. He co-wrote,

with Mayakovsky, the manifesto, “A Slap in the Face of Public

Taste”, and performed as a poet, the aim being to provoke. It’s

difficult to arrive at a fair assessment of his capabilities as an

artist from the limited number of works in the exhibition, though

it’s not hard to realise that he probably made a wise move when he

went to

It’s worth noting that the

Reviving the reputations of artists is something that needs to be

done on a regular basis, and it would seem to be the intention of

the exhibition of Francisco Iturrino’s paintings at the Museo Carmen

Thyssen. Born in

Iturrino also had a liking for large paintings of female nudes.

While they’re eye-catching in some ways, they seemed to me to be

mostly empty of any positive passion. The women appear to lack any

real character, despite in certain cases (a group in a bath house,

for example) being supposedly cheerful and active. Iturrino is

claimed as “a highly original artist”, but I didn’t understand that

from what I saw. His work is not unattractive in general, but it

didn’t comes across as having any great individuality in terms of

breaking new ground. This may be a case of a modestly talented

painter being accorded more attention than he deserves.

Henri Matisse’s “Jazz” sequence has a place in art history as an

example of how an elderly and ailing artist refused to stop creating

and produced “brightly coloured paper cut-outs”, his stated

intention being to “draw with scissors”. I’ve seen the sequence more

than once, but this viewing finally convinced me of its qualities.

Perhaps it was the straightforward way it was mounted on the walls,

and perhaps even because a tasteful piano could be heard playing

jazz in the background. I don’t usually agree with music being

played in galleries, but it proved appropriate here. Whatever,

something came together for me in a manner that hadn’t happened

before.

Picasso’s South: Andalusian References

places him firmly in the area that helped to shape him as an

artist. With a selection of his paintings ranging from his

early day in

|