|

LEAVING HOME: A

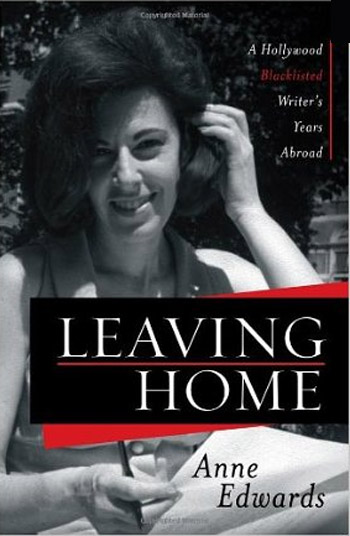

HOLLYWOOD BLACKLISTED WRITER'S YEARS ABROAD Scarecrow Press. 275 pages. £18.95. ISBN 978-0-8108-8199-0 Reviewed by Jim Burns

The purge of known left-wingers in Hollywood came in two phases. The first one, in 1947, primarily revolved around an investigation into what were referred to as nineteen unfriendly witnesses. All of them had been summoned to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in Washington. In the event only eleven of them were called on to testify. One was Bertolt Brecht whose responses to questions about his political involvements were masterpieces of evasion. The other ten became famous as The Hollywood Ten and served prison sentences for defying HUAC and therefore being in contempt of Congress. It isn't necessary to list their names here, nor to say who the others were, apart from mentioning the writer /director Robert Rossen. He will crop up later in this review. The support that the nineteen initially had from the wider Hollywood community soon collapsed when it became obvious that HUAC could easily damage reputations and careers. And the heads of the various studios had also taken fright and, despite earlier promises to the contrary, were starting their own purges of writers and others who had fallen under suspicion . HUAC returned to Hollywood in 1951, by which time the anti-communist mood in America was at its height. There was no organised resistance to the investigations and friendly witnesses lined up to testify about alleged communist infiltration of the film industry. Some of them were people who could at least lay claim to having been consistently anti-communist, but others were one-time Communist Party members who were now prepared to save their own careers by naming their one-time friends and acquaintances as communists. It was in the period between 1951 and 1954 or so that some of the worst damage was done in terms of the number of people who were blacklisted or greylisted. The latter term covered those who may not have been actually named but who were known to be a little too liberal in their ideas. This put them under enough suspicion to deter employers from hiring them. A fear spread throughout Hollywood and everyone was nervous and ensured that their actions could not be misinterpreted. It was in 1954 that the story of Anne Edwards and her years of exile from America got under way. She was a young writer recovering from an attack of polio and struggling to support herself and two children. Her husband, addicted to gambling, had left her and she was faced with being evicted because he had signed away the house to cover a gambling debt. Edwards had never been a member of the Communist Party, but knew people who were or had been, and she had signed all sorts of petitions, joined the Anti-Nazi League, and written letters of protest about cases of injustice and similar matters. When she was informed that she would soon receive a subpoena she suspected that it might be because of her friendship with Robert Rossen. And she had written a screenplay that was possibly controversial, though it hadn't been filmed. It was based on a true story of a Mexican-American who was killed in the Korean War. When his body was returned to his home-town the local funeral parlour refused to handle it and his relatives were told that, because he wasn't white, he couldn't be buried in the local cemetery. As it happened, a British producer who was in Hollywood "scouting stories and writers" had seen a TV play that Edwards had written and wanted to meet her. The upshot was that she was offered work writing a screenplay in London, so she and her children left America. Her account of arriving in Britain and how she got accustomed to the weather, the money, and other aspects of British life is worth reading, but it's the material linked to films, and in particular to the expatriate community of blacklisted American writers, that is mostly of interest. Still, one thing does intrigue me and it's her obvious fascination with Royalty. Later, Edwards wrote books about Queen Mary and the House of Windsor, the Royal sisters (Elizabeth and Margaret), and Princess Diana. It can be argued that Royalty is always a subject likely to sell, but I think her interest went further than that, and it perhaps ties in with her view of British people generally: "I held them in great respect - awe, really. When death and destruction had stalked them during the war they held fast." One of the first Americans she contacted was Lester Cole. He had worked steadily in Hollywood between 1932 and 1947, though mostly on fairly minor films, but his career had ended when he became one of the Hollywood Ten and served a year in prison for refusing to co-operate with HUAC. He never really got back into screenwriting after his release, though in the 1960s he was hired to work on Born Free. When it was first released it had to be credited to Gerald L.C.Copley, and it was only in the 1990s that Cole was acknowledged as the writer, by which time he had died. His autobiography, Hollywood Red (Ramparts Press, 1981) shows him to have retained his left-wing beliefs and his contempt for those who had compromised and named names. Edwards says that there were about thirty Hollywood expatriates in London when she arrived. And she provides some useful information about Hannah Weinstein, "a former American journalist and left-wing political activist who had come to England in 1952 a step ahead of being summoned to appear before HUAC." Weinstein set up a film production company to help blacklisted writers find work. She persuaded the BBC to start the early television series, The Adventures of Robin Hood, which starred Richard Greene. There were 137 episodes, according to Edwards, and she says she wrote four or five of them. I've read elsewhere that Ring Lardner Jnr., Ian McLellan Hunter, Robert Lees, Waldo Salt, and Adrian Scott were all hired to work on the series, with Lardner and Hunter perhaps providing the majority of the scripts. The series was also shown in America, so the names of the writers had to be disguised. The 1989 feature film, Fellow Traveller, is a fictionalised story of a blacklisted American writer's adventures in London and includes scenes which have him working on a Robin Hood TV series. The names sprinkled around Edwards' book will interest anyone with a liking for Hollywood films of the 1930s and 1940s. She mentions a dinner which was hosted by Jules Dassin. He had directed Naked City, Brute Force, and Thieves Highway in America, and Night and the City in Britain. All of these films were in what was known as the film-noir category and had a strong social content. When he was blacklisted he left America, but unlike many others he chose to move to Paris where, in due course, he directed the classic French thriller, Rififi. Edwards recalls that Sidney Buchman and Carl Foreman were also present. Buchman had been "one of the most powerful men in Hollywood, and was considered the 'golden boy' of Columbia Studios." He had been a successful screenwriter and was vice-president of the studio, but it's a sign of the impact of the blacklist that he could so easily be disposed of. Later, he was involved with the expensive blockbuster, Cleopatra, which starred Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. Edwards seems to have had a high regard for Buchman who, as well as refusing to inform on fellow filmmakers and so sacrificing his career, also appears to have acted responsibly in his business dealings with others. As for Carl Foreman, she's ambivalent. He had written the screenplay for Champion , a successful boxing picture which starred Kirk Douglas, and was involved as the writer of High Noon, a Western that became something of a classic, though Foreman's name was removed from the film when he was blacklisted. It's often said that the story is something of a parable about the blacklist in the way that the townspeople fail to support the one man who is prepared to face up to the bad guys when they arrive. Foreman moved to London but went back to the USA later in the 1950s and had a closed meeting with members of HUAC . Did he then give them the information they wanted? Edwards says that nothing was ever proved one way or the other. On his return to London he formed his own production company and hired some of the other expatriate writers to produce scripts. But he paid them "far below the established minimum wage, an action that did not endear Carl to me, nor have I ever been able to excuse it." Edwards also met Clancy Sigal, who doesn't quite fit in to the usual expatriate picture though he was a fugitive from Hollywood. Unlike most of the people she talks about, who tended to mix with each other and rarely move far out of London, Sigal ventured north and his book, Weekend in Dinlock, is an account of his friendship with a young miner who is also a talented artist. It's factual, though "Dinlock" is not an actual place and names and other details were changed. Sigal was alert to questions of class, union politics, and the clash of values that his friend "Davie" feels as his painting pulls him away from the life of a pit village and his family. It's a book still worth reading, even if the circumstances it describes have long since disappeared. I recall being told that the character of "Davie" was based on the communist miner-novelist Len Doherty who Sigal knew. Another of Sigal's books that is now unfairly forgotten, but has relevance to his leaving America when the blacklist was in operation, is his autobiographical novel, Going Away . In it the narrator drives across America, looking up old contacts with radical backgrounds and reflecting on what has happened to his country. Anne Edwards writes about her personal life in Leaving Home, though it inevitably involved men linked to films. She had a relationship with Leon Becker who was not a writer but had worked on numerous films as a technician in the sound department. It's often forgotten that many more people than writers and actors were blacklisted. Becker's name crops up frequently in the credits of films from the 1940s directed by William Wyler, Anthony Mann, Joseph Losey, and others, but his skills and reputation counted for little when the purges started. He moved to London, where he became a producer and, some years later, had a hand in the making of the Beatles first film, A Hard Day's Night. Becker had been a member of the Communist Party and it was the novelist/screenwriter Budd Schulberg who named him when appearing before HUAC. In a way Becker was lucky because he held a Canadian passport which meant that he could work quite openly in Britain. Edwards and he married, though the marriage eventually broke down. As the years passed Edwards had begun to think about writing a novel which would look at aspects of how the expatriates lived. She did eventually complete it and Shadow of a Lion was published in 1971 by Hodder & Stoughton. Its central character probably drew on more than one real-life person for personality flairs and flaws, but Robert Rossen often comes to mind. Like Rossen, he at first makes a great thing about standing up to HUAC, but later agrees to co-operate and become an informant. For the record, it seems that when Rossen did testify he named more than fifty former friends and colleagues. As an insider Edwards paints a convincing picture of the period and the effects that the blacklist had on all the parties involved. Edwards mentions Paul Jarrico, a writer she describes as "a very likeable character," though with "an inclination to speechify." By coincidence as I was working on this review I came across a DVD of All Night Long, a 1961 British film which was co-written by Jarrico, though his name didn't appear on screen. It's not a particularly good film but it does have a fair amount of interesting jazz content. Jarrico before he left America was the producer of Salt of the Earth, a film made in 1953 in difficult circumstances about a strike in New Mexico. A number of Hollywood dissidents like Herbert Biberman and Michael Wilson were also involved, and several books have been written about the problems that the makers of the film faced with financing and distribution. Larry Ceplair's The Marxist and the Movies: A Biography of Paul Jarrico (Kentucky University Press, 2007) is informative about Jarrico who, like Lester Cole, never gave up on his left-wing beliefs. The whole subject of the Hollywood blacklist, who it affected and how, and the ways in which various people found ways to survive, is of great interest. There are areas of the subject that still require clarification. For example, Edwards mentions how Carl Foreman hired blacklisted writers at cut-price rates. He's not referred to in her book, perhaps because he seems to have been active in France and Spain rather than England, but the somewhat larger-than-life Philip Yordan (not himself a victim of the blacklist) operated much the same policy with writers like Ben Maddow, Bernard Gordon, Arnaud d'Usseau, and Ben Barzman, with Yordan often taking credit when the films were shown. In the 1960s, he and his team of writers worked on blockbusters such as El Cid, 55 Days at Peking, and Custer of the West. There are numerous stories about what Yordan did and did not write, and to be fair to him some of the people he employed did recognise that he provided work for them at a time when no-one else would. Edwards does briefly comment on Joseph Losey who, she says, "had never become an integrated member of the expat community. His distancing of himself from his peers was replicated in his films where it produced a Brechtian alienation." She describes this as "a more European than American approach to film," and "intended to make spectators think rather than feel." Losey played an important role in British film-making in the 1960s and 1970s, with The Servant, King and Country, Accident , and The Go-Between being among his best work. I won't apologise for concentrating on specific parts of Leaving Home. They add something to other accounts of the blacklist years and it seems to me that they deserve to be singled out for attention. But I do want to say that the whole book is well-written and always interesting and entertaining. Anne Edwards never did get back to writing for films and television full-time, but she did go on to make a name for herself in other ways. Her list of publications includes eight novels, a couple of memoirs, and sixteen biographies. I mentioned one or two earlier, and some of the others were about Judy Garland, Vivien Leigh, Ronald Reagan, and Maria Callas. She's also written children's books. Quite an achievement.

|