|

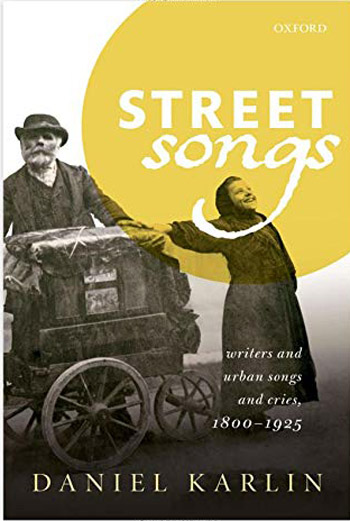

STREET

SONGS: WRITERS AND URBAN SONGS AND CRIES, 1800-1925

By Daniel Karlin

Reviewed by Jim Burns

Are there any street singers now? Some people will say “Yes”, and

point to the young men in town centres who strum a guitar and try to

imitate Bob Dylan and other popular entertainers. Others will

dismiss this suggestion, and say that such people are hardly

original in terms of them using mostly well-known songs, but how

original were earlier street singers?

Still, the contemporary singers certainly seem a long way

from the man I remember walking down the middle of a street in a

working-class area of a Northern industrial town, singing loudly.

That would have been in the mid-1940s and I can’t remember what song

he was singing, though I doubt it was one he’d composed himself or

even an old folk song. He clearly wasn’t a local drunk on his way

home from the pub, and I can only assume that he was something of an

elderly leftover from the 1930s and the dark days of the Depression.

Around the same time, I also still heard the voice of the

rag-and-bone man calling out as his horse-and-cart trundled along

the street.

Daniel Karlin surveys how some writers incorporated references to,

and sometimes quotes from songs and street cries of a (mostly) 19th

century provenance, into their work. His study largely focuses on

Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, William Wordsworth, James

Joyce, Virginia Woolf, Walt Whitman, and Marcel Proust, with

numerous additional acknowledgements to a wide range of novelists,

essayists, and poets. There were no doubt plenty of other writers,

including minor and now-forgotten figures, whose work could be

usefully explored for traces of old songs and vanished street cries,

even if they were used only for local colour. Clarence Rook’s 1898

detective story, “The Stir Outside the Café Royal”, contains the

following line: “flower girls were selling ‘nice vi’lets, sweet

vi’lets, penny a bunch’ ”.

Writers, on the whole, appear to have delighted in the noises that

could be encountered in the streets, to the extent that some thought

that it wasn’t just the songs to be heard, and the voices of traders

advertising their wares, but all the additional sounds (carriages,

conversations, etc.), that added up to what might be called the

symphony of the streets. But not everyone shared this view, and

Karlin uses Hogarth’s illustration, “The Enrag’d Musician”, to

demonstrate how a man practising with his violin has found it

impossible to concentrate because of the noises from the street. A

child beats a drum, a baby wails, a knife-grinder is busy at his

trade, a milkmaid is passing by, and the musician despairs. What one

person finds appealing another dislikes. There is often an

assumption that everyone will enjoy the cacophony of contemporary

life. Take a walk down

Karlin, in fact, refers to people who complained about the noise

from the street, and wanted street singers and traders shouting out

what was on offer, actually banned. The mathematician Charles

Babbage, who “waged a vigorous campaign against all forms of street

music in the 1860s”, included ‘The human voice in its various forms’

in his pamphlet, A Chapter on

Street Nuisances (1864)”. He was, of course, unsuccessful, it

being a fact of life that urban living inevitably brings one into

close contact with other people’s noise. And some people enjoy the

familiarity and the noise of urban life.

It’s perhaps only marginally relevant, but there was a popular song

, “Tenement Symphony”, sung by Tony Martin in an early-1940s Marx

Brothers movie, The Big Store,

which was built around the various sounds – a child crying, someone

practising on a musical instrument,

a gramophone blaring out, kids running down the stairs, etc.

– to be heard when living in a tenement. It had a romantic feeling

to it, perhaps almost influenced by a Popular Front ideology, which

may not have been shared by anyone experiencing on a daily basis the

realities of life in a tenement.

Karlin mentions a letter that Charles Lamb wrote to William

Wordsworth in which he declined “to join the nature-worshipping

choir”, giving a Whitmanesque catalogue on the sights and sounds of

Fleet Street and Covent Garden, and declaring that he ‘often shed

tears in the motley Strand from fullness of joy at so much life’ “.

Karlin will perhaps forgive me if I say that this reminds me of the

poet Frank O’Hara’s response when asked if he’d like to live in the

country. He wouldn’t mind, he said, provided there were bookshops

and bars, theatres and cinemas, galleries and other signs that

people hadn’t given up on life.

I’ve talked a little about the general outline of

Street Songs, but Karlin

is, of course, concerned to deal with specifics in terms of pointing

out where examples of a song or street cry can be discerned in a

piece of literature. It should also be noted that his book “is about

what street songs are doing in works of literature, not about the

songs themselves……..I am not “a musicologist or a historian or a

social geographer; street song has found its way into works of

literature…….what interests me is something that goes beyond mere

reference, or that adds local colour to a realist fiction: something

that plays a specific part in an artistic design”.

A good idea of what Karlin is aiming for can be seen in his chapters

on the work of Elizabeth Barrett Browning (EBB) and Robert Browning

(RB). Living in

Other questions occur. The Brownings were not living in Casa Guidi

when she started writing the poem. Various versions of the poem have

different titles, and so on. Does it matter? The test is whether or

not the finished poem achieves the effect the poet was striving for?

: “The child singer is a made-up figure; he is not there by

accident”. The poem is a construct, meant to impart a message about

liberty, and, as Karlin notes, it is something of a riposte to those

poets and others who indulge in a “self-indulgent, lettered

tradition of melancholy, of lamentations over

I have to say that Karlin’s attention to the historical and

political background in the work he discusses is extremely helpful.

I don’t imagine that all that many people are familiar with the

intricacies of nineteenth century Italian history before

unification. They may know a little more about events in

In Ulysses a one-legged

sailor wanders the streets and sings a few words from “The Death of

Nelson”, a “well-known ballad”. Other songs and poems – around 400,

according to Karlin, quoting Don Gifford’s

Ulysses Annotated – are

scattered around Joyce’s book, though not in an arbitrary fashion.

They are mostly there to buttress the narrative by illustrating what

is going in the minds of the characters, who, as Karlin says,

remember occasions when they heard the song or poem in question. And

there are songs that are performed on the streets in varying

circumstances.

The one-legged sailor singing “The Death of Nelson” has already been

mentioned. “The Boys of Wexford” is an Irish rebel song, with its

roots in the failed 1798 uprising and the battle of Vinegar Hill. A

prostitute sings a bawdy song about “the leg of the duck” that

hasn’t been identified, though Karlin doubts it was something that

Joyce made up. A

popular song, “My Girl’s a Yorkshire Girl”, is played on a pianola

in a brothel. Is its use an indication of the presence of British

soldiers in

It’s fascinating to follow

Karlin’s line of analysis as he places these songs in context and

explains their relevance to the development of the novel. And

instructive for those, like me, who love to read about the origins

of fragments of songs that crop up in novels. When Molly whistles

the tune of “there is a charming girl I love”, Karlin says that the

correct title is “It is a charming girl I love”, and it derives from

“The Lily of Killarney, a

light opera based on Dion Boucicault’s high Victorian melodrama

The Colleen Bawn (1860)”.

Boucicault’s play is still occasionally performed, but it’s doubtful

if The Lily of Killarney

will see the light of day again.

What enhances Karlin’s close textual analysis of the poems and books

he studies is his enthusiasm, something which is especially evident

in his chapter on Walt Whitman. And what a pleasure it is to see

someone paying attention to the American poet. Karlin looks at

Whitman’s poem, “Sparkles from the Wheel”, in which the poet joins

(not just observes) a group of children as they watch a

knife-grinder at work. My own memories stretch back far enough to

seeing what must have been one of the last of his kind at work in

the street, and to being interested in what he was doing.

Karlin draws our attention to the fact that it was hard work. We

talk about the “daily grind” and “keeping our noses to the

grindstone”, a phrase that brings to mind the knife-grinder bent

over his wheel. There is an amusing passage which deals with a

satirical poem, “The Friends of Humanity, and the Knife-grinder”, in

which a well-meaning liberal questions a down-at-heel knife-grinder

because his impoverished appearance suggests exploitation “by the

rich and powerful”. The man turns out to be fiercely independent,

rejects any interest in politics, and indicates that the liberal’s

concern and philanthropy ought to extend to giving him sixpence so

he can buy a pot of beer.

In Virginia Woolf’s Mrs

Dalloway, an old woman is seen near Regent’s Park underground

station “singing” what seems to be a wordless and most probably

tuneless song: “ee um fah um so/foo swee too eem so”, which puts me

in mind of the Dada performances at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich

in 1916, and of children chanting nonsense rhymes. But Karlin,

quoting an “incomprehensible song” that some children sing in

another work by Virginia Woolf, asserts that it is “fundamentally

different” to the old woman’s “song”, being well in the

compositional tradition of “innumerable ballads, hymns, popular

songs, and nursery rhymes”.

There is so much more packed into each page of

Street Songs that it

would be possible to carry on talking about it almost endlessly.

Proust makes an appearance, and in

Remembrance of Things Past,

Marcel “may be thought of as a kind of aural

flâneur, enjoying and

consuming the sounds of the city as they are brought to his ears”.

He “hears or mentions a score of cries relating to food”, and the

cries of numerous other street traders, such as the old-clothes man,

the knife-grinder, and many more. There is an “erotic energy of the

great city” and street cries suggest this. Karlin brings in

references to Charpentier’s opera,

Louise, in which

Street Songs

is clearly an academic work, thoroughly researched, with extensive

notes, and intense analysis of its basic material. But it strikes me

that it can be read to advantage by those who may not be involved in

academic studies, but who have an interest in literature. It is

clearly written, and even entertaining, which is not something that

can always be said about academic texts.

|