|

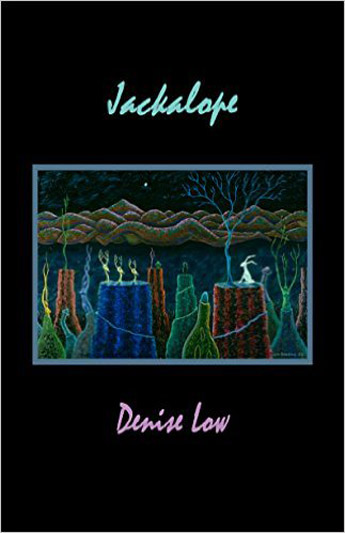

JACKALOPE By Denise Low Red Mountain Press. 152 pages. $19.95. Available in Britain from Amazon uk. Reviewed By Fred Whitehead

I don’t know if jackalopes exist in Britain, but in the western U.S.A. they are occasionally met with in tourist curio shops, which is where I acquired mine decades ago. They are or by appearance seem to be a union between an antelope and a jackrabbit. Little antlers growing conspicuously from the rabbit’s head. Copious examples are to be seen via a search at Google Images. Jackrabbits (Lepus californicus) are actually hares, the third largest in North America. However it happened, the jackalope has a strange kind of existence in American folklore and popular culture. Denise Low, a distinguished writer, was the Kansas Poet Laureate in 2007-2009, and has authored some 25 books, including poetry, fiction, literary history and essays. She founded Mammoth Publications in Lawrence, Kansas, and is now retired from the faculty of Haskell Indian Nations University. Jackalope is a collection of short chapters, centered around one such creature and its experiences in a range of western locales, especially bars, saloons and beer joints, of which more in a moment. I say “its” because it takes two forms: Jack (male) and Jaq (female). Rumored to be hermaphrodite, our ‘lope prefers the word intersex, because it can switch genders. Feeling uneasy and threatened in a rough bar, “Her testosterone surges as well as adrenaline, and she begins to shift into masculine mode . . . Jaq feels electrical energy travel from her head to her toes.” There’s a lot of that electrical energy in these stories: sand storms, solar flares, lightning strikes, the buzz of alcohol, barroom brawls, video games: everyone and everything is wired someway. Feelings themselves, I suppose, are a form of energy. The book takes shape in a series of episodes, drawn together by the appearance and re-appearance of Jack/Jaq. Much energy manifests itself in conversations—tall tales, and jokes (“A jackalope comes into a bar and orders . . . “). Early on, there’s a chapter “Jackalope Walks into an Art History Lecture.” Of course, there are numerous illustrative slides, with commentaries. One such: “The script indicates the inhabitants of Tannin Island gifted this horned rabbit to Alexander the Great, after he slew the local dragon. This apotheosized gaze re-directs the hegemonic priest class to the circum-Mediterranean deification cult of Hellenic rulers. . . .” A stream of outlandish pedantic speculations and conjectures ensues, with hilarious effect. Anyone who has grimly endured similar presentations will feel right at home. Other chapters are set in strange, bizarre places: a paranormal conference, a gyno-urologist’s office, a Sherman Alexie narrative, a Colorado billboard, a writers’ conference, a Gilgamesh tablet, and numerous bars and casinos. Always there is a sharply observed visual scene. In a truck stop: “Jack looks at his reflection in the convex mirror over the door of the High Plains Gas and Go. His antlers distort into a maze of contorted twists, crazy looking. Sometimes he doesn’t believe he is real, either . . . On the way out, he stops and pulls three liters of bottled water out of the refrigerator case. In the shimmering glass reflections, oddly, he sees a floating American Indian woman caught in a net. He turns. Behind him is a shelf of kitsch for sale: Pocahontas is snared inside a macramé dream-catcher. Beside her, a ceramic Lakota man paddles a canoe. A bronze Apache man wrestles an alligator. Jack sighs. What bad mismatches of tribes and geographies.” Well, there are so many mismatches and discordant connections in this book, in this whole country. Always present, sometimes accurately, sometimes distortedly, are the Native Americans, who keep showing up in the bars—witnesses and active participants in American society. Remembering the past, they acutely perceive the present, and how all of that is connecting to any possible future. Many of the whites are content to brawl and fight each other; a few know their history too. Part of the fun of the book is the challenge of sorting out what is fantasy, and what is real. Sometimes I just gave up and enjoyed the stories. The conversations, alone worth the price of admission, are like riffs in jazz, one never knows where they are going or where they will end. In sum, I haven’t had such continuous pleasure in a book for a while. In it, archetypes collide with post-modern chaos theory, folkore is fused with true sophistication, all delivered with panache, clever and even sly. It’s a roadtrip through the American west: enjoy the ride.

|