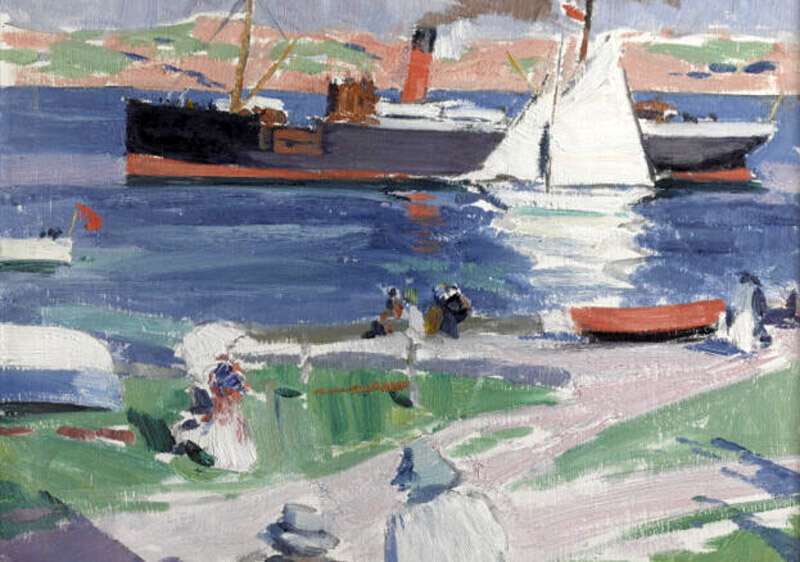

COLOUR AND LIGHT : SCOTTISH COLOURISTS FROM THE FLEMING COLLECTION

Graves Art Gallery, Sheffield. Until 9th December, 2023

Reviewed by Jim Burns

I’ve previously written about the Scottish Colourists (S.J, Peploe, J.D.

Fergusson, F.C.B. Cadell and Leslie Hunter) when I reviewed an exhibition in

Kendal in late-2019 and early-2020 (see

Northern Review of Books,

November 2019). What I said then bears repeating now. Their work is still,

to my mind, not seen often enough, either in terms of individual selections

or as a group. To quote James Knox, who wrote a useful small book about the

four artists, they were “one of the most talented, experimental and

distinctive groups in 20th century British art”.

What is significant about the four painters is that, although sharing

interests and some experiences, especially with regard to studying and

working on the Continent, with Paris as a key focus, they each had

individually-identifiable styles. Peploe and Fergusson had both studied in

Paris and were initially influenced by Manet and Whistler but quickly fell

under the influence of the Fauves, noted for their use of bright colours.

Cadell and Hunter came along a little later. The latter had lived for a time

in San Francisco where he produced illustrations for books and magazines.

When he returned to Edinburgh he combined studying old masters and new

French artists to produce paintings which showed the influence of Matisse.

As for Cadell, he had gone to Paris at the age of sixteen to study at the

Académie Julian and had also spent a year in Munich. His first major

influences were the Impressionists, but he moved towards a looser technique

and “boldness of colour”.

The Colourists did attract some attention before the First World War and in

the 1920s, but the 1930s found their fortunes at a low ebb. Hunter died in

1931 after suffering from “nerve attacks” which resulted in a “creative

block and problem with this dealers”. Peploe died in 1935, possibly during a

flu epidemic, and Cadell died in poverty in 1937. He had never been very

business-like and the collapse of the art market during the Great Depression

meant that his paintings didn’t sell. It may have also been true that the

work of the Colourists, which was often about cafés, restaurants, night

life, sunny days and pleasure, did not fit easily into the darker political

mood of the Thirties. Only Fergusson seems to have survived both as man and

artist. He returned to Scotland with his partner, Margaret Morris, and

became an active member of the Scottish art scene, “writing, editing and

founding groups and clubs”. His years on the Continent had given him a taste

for café culture.

The reference to Margaret Morris reminds me that there is a small painting

by her in the exhibition. She was primarily a dancer and teacher, as well as

Fergusson’s muse and companion in his various ventures. And I was

particularly impressed by the work from the Graves’ own collection of John

McLauchlan Milne, an artist I knew little about but who was sometimes

referred to as the “Fifth Colourist”. It’s easy to see the link with the

others in his colourful canvases.

Visitors to the Scottish Colourist’s exhibition ought to wander into the

adjoining rooms to see what’s on display. Sheffield has a decent collection

of “Modern European” with works by Cezanne, Renoir, a very fine Alfred

Sisley and much more. In another room a range of portraits from across the

years has its attractions. For me these included a typically large and

bright John Bratby portrait of Antonia Fraser, a small but striking Ben

Nicolson, Percy Horton’s 1929

Unemployed Man, and Kees Van Dongen’s eye-catching

Kiki of Montparnasse which

captures some of the outrageous flamboyancy of this entertainer of bohemian

Paris.

I referred to a book by James Knox,

The Scottish Colourists, published by the Fleming Collection in 2019.

It’s on sale in the gallery and is a good short introduction to their work.

.