|

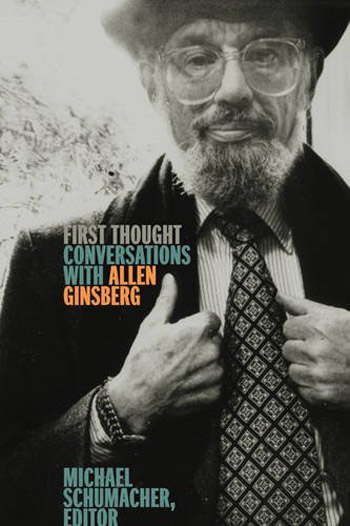

FIRST THOUGHT : CONVERSATIONS WITH ALLEN GINSBERG

Edited by Michael Schumacher

University

of Minnesota

Press. 264 pages. $19.95. ISBN 978-0-8166-9917-9

Reviewed by Jim Burns

I’m not sure how many interviews Allen Ginsberg gave over the years.

Some of them probably never made it into print, or may have appeared

in ephemeral publications that no-one now remembers. Michael

Schumacher says that: “Ginsberg considered interviews to be a vital

part of his work, as one might surmise from the titles of two

previously published anthologies of interviews:

Composed on the Tongue, a

relatively slender collection edited by Don Allen and issued by Grey

Fox Press in 1980, and

Spontaneous Mind, a hefty volume edited by David Carter and

published by HarperCollins three years after Ginsberg’s death in

1997”.

That Ginsberg was a good interviewee, both happily responsive to

questions and informative, I can testify to myself. I interviewed

him for Beat Scene

magazine in 1990 when he was in

London

for readings. I have a recollection that someone from

The Daily Telegraph also

interviewed him around the same time. Probably, like other

interviews, they’ve disappeared from view unless an earnest

researcher finds them. But I did try to give my own encounter with

Ginsberg a degree of extra life by including it in my book,

Beats, Bohemians and

Intellectuals, published by Trent Books in 2000. This wasn’t so

much to enhance my own reputation as to give some of Ginsberg’s

comments a little more permanency. I had been particularly intrigued

by what he’d said about the influence of Ben Maddow’s 1930s poem,

The City, on the writing

of Howl. If nothing else,

my interview with Ginsberg had highlighted that fact.

Michael Schumacher’s selection of interviews uses material that

wasn’t in either of the collections referred to earlier. And the

first one in his book is particularly interesting. The journalist,

Al Aranowitz, had written a series of articles about Beat Generation

writers for The New York Post,

and expanded one of them into the longer “Portrait of a Beat” that

was published in 1960 in

Nugget, one of the slick “men’s magazines” then cashing in on

the interest in the Beats. Aranowitz, to give him his due, was

generally sympathetic towards what Ginsberg, Gary Snyder, and

others, were doing, and generally managed to balance journalistic

needs to appeal to a broad readership with some intelligent comments

about Beat aims and achievements in their writings.

It’s a personal reminiscence that, in order to find copies of

Nugget and other similar

magazines (Swank, for

example, which around 1960 published several sections of

Beat-related writing), I had to prowl around various sleazy,

back-street bookshops which stocked them. Respectable shops didn’t

sell publications like those in early-1960s England. My forays into the nether

world of mild titillation on display (Nugget

and Swank each had a

few fairly innocuous photos scattered

around their pages), and pornography under the counter, paid

off, and I got to read things like the Aranowitz interview with

Ginsberg in Nugget which

were probably overlooked by most people.

It was in his conversation with Aranowitz that Ginsberg claimed that

the Beats were “prophets howling in the wilderness against a crazy

civilisation”. It was a typical Ginsberg statement, and very much in

line with his need to propagate a cause and indulge in generous

promotions of his fellow writers, such as Jack Kerouac, William

Burroughs, and Gregory Corso. And it makes one realise that, had it

not been for Ginsberg, there may well never have been a Beat

Generation, or at least not in a way that, for a time at least,

attracted a great deal of attention from journalists, intellectuals,

and some parts of the general public. He was the man who, in a

sense, sold the idea to other people. Had it not been for him some

writers may never have been published, and those that were may have

been just passing fancies on the bohemian fringes of the literary

scene.

Ginsberg combined the enthusiasms of an old-style radical organiser

with those of a talented and skilled poet. He would never have got

away with being simply a publicist for the others had he not created

some striking poetry himself. Long Poems such as “Howl”, “Kaddish”,

and relatively shorter ones like “America”

and “A Supermarket in

California”, gave him a credibility that

allowed him to speak authoritatively about writing generally. Some

writers prefer not to talk about writing in any great detail, but

Ginsberg wasn’t one of them. There is an interview, conducted by

Kenneth Koch, himself a poet, in the 1970s, and it’s useful to read

(hear?) Ginsberg explaining about what influences him and how he

writes a poem: “On the other hand, I write a little bit every other

day. I just write when I have a thought. Sometimes I have big

thoughts, sometimes little thoughts. The deal is to accept whatever

comes. Or work with whatever comes. Leave yourself open”.

Music was something that Ginsberg liked to evoke as influential on

his work, and in the interview that is headed, “Words, and Music,

Music, Music”, he talks about the various forms of music that he

heard and found interesting. I have to admit to a personal prejudice

in favour of his comments on the jazz of the 1940s, and his

introduction to bebop through Jack Kerouac and Seymour Wyse.

Ginsberg often said that he was influenced by tenor-saxophonist

Lester Young’s playing, and in the interview he also mentions

another tenorman, Illinois Jacquet, and claims him as an additional

influence.

I’m always intrigued by Ginsberg’s capacity to name people –

musicians, writers, philosophers, etc. – as influences, almost at

the drop of a hat, and I can’t help wondering whether or not there

wasn’t an element of myth-making in what he was doing, and that he

was, in a sense, laying the ground for future scholars to carry out

research into those he named. And their possible presence in his

poems. And, in this case, to pursue the supposed connection between

words and music.

As Ginsberg moved on he involved himself more and more with pop

music, associating with Bob Dylan, the Beatles, and others. I’ve

always been curious about the motives for his activities in that

line. Did he genuinely believe that it was a way to draw attention

to poetry (not necessarily just his own), and take it to a younger

audience, or was there a degree of opportunism in the way he seemed

to enjoy mixing with celebrities? I’m probably risking incurring the

wrath of those to whom Ginsberg was something of a guru by asking

such a question, but if I dare suggest that his poetry mostly

declined in quality after his productive days in the 1950s and early

1960s, it may be that he needed to find ways to stay in the

limelight.

That Ginsberg liked to ramble around matters that he was concerned

about, such as censorship, legalisation of drugs, sexual repression,

anti-Vietnam protests, etc., is obvious from this assembly of

interviews. And the usefulness of the material may depend very much

on what a reader’s interests happen to be. From my own point of

view, it’s handy to read him reminiscing about

San Francisco

in the 1950s, before the Beat boom drew in more people, not all of

them necessarily with a deep involvement with poetry. Asked if there

were a lot of people who were a part of the scene, he replied: “No,

just thirty to forty people. But they all knew each other so that

seemed like a lot. They were all poets. Robert Duncan would come out

and give a reading, and whenever there was a reading afterwards

everybody would go to the same place. ‘The Place’. That’s back in

the mid-50s. There was a kind of camaraderie, and then, later,

around 1958-59, there were a lot of music, poetry places…..jazz

poetry places. But originally it was just straight poetry”.

I find that valuable, more so than Ginsberg pontificating about

drugs, and it helps towards an understanding of what was taking

place on the West Coast in the 1950s. But I suppose it will be

argued that Ginsberg wasn’t just a poet, he was a poet with a wider

social and political purpose, hence his need to give numerous

interviews and have opinions on just about everything.

To be fair, there is much of interest to be found in the interviews.

He talks about his experiences when he was expelled from both Cuba and Czechoslovakia. There is a joint

interview with Ginsberg, William Burroughs, and Norman Mailer, that

has things to say about writers and writing, and another when

Ginsberg was interviewed alongside his father, Louis Ginsberg,

himself a poet, though of a very different kind to his son. He was a

different sort of personality, too, and was much quieter, both in

person and as a writer. But in his day Louis Ginsberg had appeared

in anthologies such as May

Days: An Anthology of Verse from Masses-Liberator, and Louis

Untermeyer’s Modern American

Poetry.

There was something about Allen Ginsberg which, whatever one thought

of his poetry, was quite appealing. He seemed generous in his

appraisals of other poets’ work, and he had the gift of loyalty to

his old friends of the Beat Generation. When asked about the

“philosophies” of the Beat, he replied: “We didn’t have what you

could call a philosophy. I would say that there was an ethos, that

there were ideas, and there were themes, and there were

preoccupations”. It was a good way of summing up what the Beats were

about.

First Thought

is a fascinating book in many ways. As I said

earlier, what Ginsberg talks about may be of interest according to

one’s inclinations towards various subjects. I certainly got a great

deal out of it.

|