|

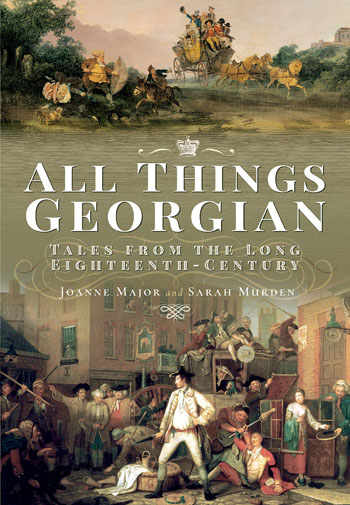

ALL THINGS GEORGIAN : TALES FROM THE LONG EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY

By Joanne Major and Sarah Murden

Pen & Sword Books. 170 pages. £16.99. ISBN 978-52675-785-2

HOGARTH : PLACES AND PROGRESS

An exhibition at the Sir John Soane’s Museum,

TWO LAST NIGHTS! : SHOW BUSINESS IN GEORGIAN

An exhibition at The Foundling Museum,

Reviewed by Jim Burns

The “long eighteenth century” ran from the late-seventeenth century

to the eighteen-thirties, according to the authors of this book. And

it’s probably fair enough to accept that, from the point of view of

manners and morals, there was a kind of continuity of behaviour that

marked the period concerned. After 1830 or so things began to

change. Queen

It may be that, because things appeared to be much more on display

in the eighteenth-century, there is a greater level of material to

be drawn on when surveying the relevant years. Think of Hogarth,

Rowlandson, Gillray, and others. Artists satirised the antics of the

upper-classes, and in Hogarth’s case laid down morality tales about

wastrel young men disposing of their inheritances in riotous living,

and innocent young women being drawn into lives of depravity. The

lower-classes didn’t come off any better and were shown as addicted

to drink and cruel sports. It could all be made to seem great fun,

as in Pierce Egan’s Life in

London, which chronicles the “rambles and sprees” of Jerry

Hawthorn, Corinthian Tom, and Bob Logic.

All Things Georgian

doesn’t claim to be a complete history of the Georgian era, but

instead selects certain individuals and incidents to illustrate

certain aspects of a time when society was in a state of flux,

cities were rapidly expanding, and it was often easy for those with

a flair for flamboyant persuasion, and the gift of the gab, to

re-invent themselves. Sarah Wilson was a kitchen-maid in a “grand

home in Leicester Fields (now

When she re-appeared, it was in Great Budworth in

Her mistake appears to have been that she returned to

Con-artists are known in every age, of course, but Sarah perhaps

succeeded easily with her frauds because communications were limited

in the late-eighteenth century, and once out of

Actresses frequently crop up in

All Things Georgian where

they beguile earls and dukes, and become mistresses of princes and

even kings. Elizabeth Hartley “was a striking red-headed beauty with

a lively disposition”.

Like some other celebrated females, she seems to have spent some

time working in a brothel run by a Mrs Kelly. Emma Hamilton, who

later married Lord Nelson, also functioned as one of Mrs Kelly’s

girls. The celebrated painter¸ Sir Joshua Reynolds, painted

Hartley’s portrait while she was living with Kelly, but she soon ran

off with a young man who frequented the establishment. When they

were short of money she was persuaded to go on the stage, an

occupation which wasn’t looked on as respectable in polite circles,

even if wealthy and titled men competed for the favours of

actresses. She had more than one affair, and there was even the

threat of a duel being fought over her, but when her health declined

she retired and lived quietly until she died at the age of 73.

She wasn’t as colourful as Lavinia Fenton who was said to have been

a “whore, waitress and barmaid” before taking to the stage, where

she was a great success in John Gay’s

The Beggar’s Opera. She

attracted the attention of the Duke of Bolton, and Hogarth portrayed

them both, she on stage, he looking on, when he painted a scene from

the opera. She lived as

Every age has its characters, but the eighteenth century seems to

have abounded in them. The “wicked” Lord Lyttelton “enjoyed a

reputation as both a libertine and a politician”. Like many men of

his kind he was always on the lookout for a woman with money, and he

married a wealthy widow primarily for the £20,000 she had. When the

ceremony was over he promptly left for

It’s not all flighty women and money-grubbing men. The parade of

oddballs and eccentrics includes Sir Joseph Banks, a botanist and

naturalist with a place in history. He accompanied Captain Cook on

one of his voyages to the Pacific where, when they landed in Tahiti,

Banks found himself a compliant female companion despite having left

behind a fiancé in

Arsonists, including one, a religious maniac, who attempted to burn

down York Cathedral, make an appearance. And there was Jenny

Cameron, a “Female Imposter” who wore male clothing and claimed to

have fought alongside her husband, an officer in Bonnie Prince

Charlie’s army when the Jacobite cause received its death blow at

Culloden. There were attempts to assassinate Royalty which were

usually the actions of deranged people who went to the asylum and

not the gallows. And the “Resurrection Men”, or body-snatchers as

they were commonly known, who specialised in digging up fresh bodies

and selling them to medical schools so student could practice

dissection. If caught, the common thieves were usually punished

while the surgeons and others who encouraged the practice were

invariably never prosecuted. They even justified it as a necessity.

Coffee-houses, balloon-flights, a zebra given as a gift to Queen

Charlotte, which became an object of attention, (Stubbs did a

painting of the animal) and was popularly known as “The Queen’s

Ass”, smugglers, and

much more can be found in the pages of this entertaining, if

capricious (in terms of the selection of material) book. It’s

anecdotal, and anyone wanting a deep survey of social and economic

factors relating to Georgian Britain will need to look elsewhere.

But it is lively and well-illustrated, and in a small way can be

quite instructive about social class and its effects. The means by

which women, in particular, were very much at the mercy of men are

easy to discern as their stories unfold. Brothels and/or the stage

were often how to avoid poverty and sometimes climb higher up the

social ladder. When a woman had money and position she was

frequently a target for adventurers, and could easily be stripped of

her fortune and then deserted. The Georgian Age had its colourful

side, but also its darker aspects which are too easy to overlook.

It makes me wonder whether the unnamed woman made pregnant by Joseph

Banks had occasion to visit The Foundling Hospital where unwanted

babies could be handed in and cared for? An exhibition at the

William Hogarth was well-aware of the pitfalls facing many people in

London, and his series of paintings, “A Rake’s Progress” and “A

Harlot’s Progress”, had a moral purpose as they traced the downfall

of a young man foolishly squandering his inheritance in brothels and

gambling dens, and a similar story of a naïve country girl arriving

in the city and being enticed into prostitution. Hogarth painted

other series, including “The Humours of an Election” and “Marriage a

la Mode”, and they are all to be seen in the small exhibition at the

Soane’s Museum. There are also gems such as the familiar “

|