|

FROM OUR

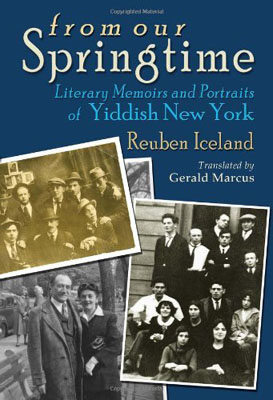

SPRINGTIME: LITERARY MEMOIRS AND PORTRAITS OF YIDDISH NEW YORK

PROLETPEN:

AMERICA'S REBEL YIDDISH POETS edited by Amelia Glaser and David Weintraub.

Translated by Amelia Glaser. Reviewed by Jim Burns

"One of the things that distinguished the Jewish migration to America, and set it apart from the journeys of other ethnic groups, is the fact that the Jews brought their intellectuals - their writers, their thinkers - with them..... There was very little place for Jewish intellectuals in the cultural life of east European countries. Consequently, many of them came here along with the masses of ordinary Jews, thereby enriching the Yiddish culture that the immigrants would build up in America." That excerpt from How We Lived:A Documentary History of Immigrant Jews in America 1880-1930 by Irving Howe and Kenneth Libo provides a useful introduction to the two books under review. What needs to be stressed is that the intellectuals and writers referred to did not establish themselves in the existing literary set-up in New York, the city where so many of the Jews flooding in from Europe settled. It was necessary to create newspapers and magazines for a readership that had Yiddish as its main language. And as a major portion of that readership was not sophisticated in its tastes, it expected its poets (who we are mostly concerned with here) to produce work which dealt with the sort of conditions experienced in the tenements and sweatshops of the city. The earliest Yiddish poets in America, such as Morris Winchevsky and Morris Rosenfeld, had direct contacts with the lives of poor Jews and their writing illustrated that fact. Winchevsky, who had been associated with the German socialist movement and had also spent time in the East End of London, wrote some stark "London Silhouettes" which could just as easily be read as applicable to the East Side of New York:

The youngest is

out selling flowers; And Morris Rosenfeld, who Irving Howe in his monumental World of Our Fathers: The Journey of the East European Jews to America and the Life they Found and Made called "the most gifted of the sweatshop poets", wrote poems which focused on problems that his readers would easily identify with. His "My Little Boy" was a heartfelt lament about having to work such long hours that he never has time to see his son other than when he's asleep. In another poem he summed up what it was like to work at a repetitive job and become almost like a machine:

I work, and I

work, without rhyme, without reason – Winchevsky, Rosenfeld, and others like them, may have been popular with Yiddish-speaking sweatshop workers, but their approach to poetry was eventually questioned by some younger poets, and was mockingly referred to as "the rhyme department of the Jewish labour movement." In 1907, a group of poets got together and started a magazine called Yugend (Youth) which would represent their ideals of a poetry that would not be tied to political commitment, even if most of the poets would probably have thought of themselves as socialists. Irving Howe later said that "ideas of aesthetic autonomy and symbolist refinement" were highlights of their work. It should not be assumed that, because they turned away from writing about social and economic problems, the poets linked to Di Yunge (the name given to the new movement) were detached from the everyday lives of their fellow-Jews. Most of them worked in the sweatshops, or had jobs as painters and decorators, night watchmen, and shoemakers. Their lives weren't easy, by any means, and it might be thought that, by writing poetry that was often intensely lyrical, they were setting up defences against a crude and repressive world. Reuben Iceland, one of the founder members of Di Yunge, tells how he couldn't wait to get away from his job and head for the cafe or other location where his friends gathered to talk. He tried running a small store for a time, but it failed, though he does say that it became a hang-out for his fellow-poets. And there's a story, humorous in its way, about how he got so involved talking with friends that he forgot all about his wife and daughter and a promise he'd made to take them out. His wife no doubt wasn't amused, and one gets the feeling that families often had to put up with a degree of waywardness on the part of the poets. Iceland remarks: "To miss a day of work often meant not having a pair of shoes for a child or lacking three dollars for rent. Yet when you entered the cellar, you found friends whom you knew should have been at work in the shop." But I'm possibly being too moralistic, and it's true that, reading Iceland, it's difficult not to be moved by the enthusiasm and dedication he and his friends displayed. The following is from the opening pages of his memoir :

Iceland mentions that he was working as a packer in a hat factory around the time he met Landau, and that Landau was already married and had a child. They were not the kind of young poets who came from middle-class families and had been to university. Nor were they likely to ever obtain lucrative jobs. Mundane work, low pay, and the constant threat of unemployment in a country with little welfare provision was a more likely scenario for them. Iceland does say that a few of the sixty or seventy people who attended meetings of a group which published two anthologies did go on to become journalists, union leaders, doctors, dentists, and businessmen, so some forms of advancement were possible, but few of them remained writers. The dedicated poets, on the other hand, were too engrossed in their poems to succeed in other fields. Zishe Landau was suspicious of success, especially if he thought that it had been achieved by cultivating publicity or consorting with critics and editors. There were casualties, as might be expected in any group likely to have a number of sensitive individuals in its ranks. Moyse Warshawe, who Iceland says "felt at home only with a book," worked as a night watchman and threw himself off an upper floor of a building that was under construction. Another poet, "for whom everyone had great hopes," suddenly disappeared and later turned up in Detroit, working as a salesman. In a memoir of Abraham Liessen, who Iceland describes as "an authentic and seminal poet," there's a sad story of how his three-volume collected poems didn't sell and were "left in a cellar gathering dust." A lack of response to her book drove Anna Margolin, Iceland's long-time companion, into near-silence for many years. His account of her decline and death is a moving tale of a bright spirit defeated by indifference. There were, probably inevitably, differences of opinion and clashes of personality in the Di Yunge group, and soon a new movement called The Introspectivist Poets came to the fore. Irving Howe pointed out that they "had received a certain amount of education in America, some going to college for a time." He added that few of the Di Yunge poets ever really mastered English, whereas the Introspectivists had "read, or would soon be reading, Pound, H.D., Eliot, and Stevens." Unlike the earlier poets they "turned to free verse, intensely personal themes, incongruities of diction and sounds." What had happened was that younger poets had become more attuned to America and the modern world generally. Irving Howe devotes several pages of The World of our Fathers to Di Yunge and its role as the first definable literary movement in the area of American Yiddish poetry. He also refers to the Introspectivist poets. But you won't find a record of the Proletpen poets in his book. Can we pin down a reason for that beyond the fact that Howe may not have seen their work as having any lasting value? Dovid Katz, in his excellent introduction, hints at a "McCarthyesque political litmus test," and says that Howe belonged to the "socialist but anti-Soviet camp." Was his judgement about whether or not to give space to Proletpen influnced by the largely pro-Soviet stance of the poets linked to it? Many of them were communist, or communist sympathisers, in the 1930s and 1940s. Katz indicates that the 1920s saw "a new wave of immigration to New York that brought a lot of fresh young writers who would make their debuts in the early or mid-1920s, and by a new and different kind of politicisation." These writers were often not directly involved in the daily grind of the sweatshops, or at least not to the extent that the Di Yunge poets were. But this may be a generalisation, and it's difficult to be certain without the necessary evidence about their careers. The notes about the poets in Proletpen do record that some had worked in factories and in the garment trades, but others were teachers, editors, and librarians. They may have belonged to Proletpen but were not proletarians. Proletpen was a writers' union, founded in 1929 and in existence until 1938 when it was incorporated into another organisation. Prior to its formation a magazine called Yung Kuznye (Young Forge), edited by Alexander Pomerantz, had published many of the poets who joined Proletpen They also published in Frayhayt, a newspaper established by Moyshe Olgin in 1922 as a rival to Abraham Cahan's Forverts. Frayhayt was pro-Soviet but Forverts, though socialist in its intentions, always questioned what was taking place in Russia. This needs to be seen in context, because the front page of Forverts had the slogans, "Workers of the World Unite" and "Liberation of the workers depends on the workers themselves" on either side of its title. The difference between it and Frayhayt often revolved around their differing attitudes towards communism. Dovid Katz's informative introduction gives a detailed account of the various factions and individuals in the Proletpen group. Some poets were more concerned with what Katz refers to as "art for the sake of art," while others thought that poetry should address immediate social and political issues. But, as he suggests, the line between them wasn't firmly drawn, and poets crossed it when necessary. He includes Yosl Grinshpan, who died "probably of starvation during the Great Depression" in New York in 1934, among the "art for the sake of art" poets, but his poems in Proletpen have titles like "The Miner's Family" and "Vanzetti's Ghost," which indicate a sensibility aware of what was happening outside the realm of art. It could be that these poems are not representative of Grinshpan's work, and were chosen because they fitted in with the idea of "America's Rebel Yiddish Poets." I'm not in a position to comment on this. Or was it that Grinshpan's style differed from that of "proletarian" poets who might be more interested in making a statement than in shaping a well-structured poem? Again, I find myself at a disadvantage in that I have to rely on the translations. Reading the poems in their original Yiddish might provide me with a different perspective. Over the years there were arguments among the Proletpen poets, such as when Menke Katz's The Burning Village aroused controversy for "being steeped in the past, in the Jewish shtetl and ancient Jewish traditions, for not bringing happiness to working people and for ignoring the entire list of requirements for 'constructivist’ poetry." An earlier Katz book, Three Sisters, had led to him being expelled from Proletpen because it was said to be "steeped in mysticism and eroticism," and was published against the wishes of Proletpen officials. The Burning Village was attacked by proletarians such as Aaron Kurtz and Martin Birnbaum, but Katz sturdily defended his freedom to write as he liked. There are plenty of memorable poems in Proletpen including Yuri Suhl's "Winter," where the attractive setting that frost and icicles can present is contrasted with the desperation of being homeless in winter and forced to survive on the streets. Or Y.A. Rontsh's "Done a Good Job," in which a bigoted white southerner describes a lynching. The poem ends with the following lines:

Done a good job, It isn't all politics, though, and there's a small selection of love poems, among which those by Dora Teitelboim stand out. But the overall tone is of poets concerned to deal with social and political matters. It's claimed that the Proletpen poets were "the direct literary descendants of the American Yiddish labour poets." The main difference seems to me to be that Proletpen members were more or less consciously following a line laid down by the Communist Party, and they looked beyond the problems of Jews working in the sweatshops of New York and, perhaps, thinking about what they'd left behind. Proletpen poets wrote about the Spanish Civil War, strikes around America, racial troubles, as well as what they'd seen in New York. From Our Springtime and Proletpen are fascinating books and full of information about a world of poetry that, I suspect, will be mostly unfamiliar to readers of poetry in Britain. It's probable that, even in America, the names of the majority of the poets referred to will mean little other than to a few specialists and enthusiasts. Yiddish fell out of favour for many years. It was too often associated with the old immigrant society of Yiddish speakers and the ghetto of the East Side of New York with its poverty and old-fashioned habits. Many Jews in the 1950s and after wanted to break away from all that and establish lives in the suburbs and be assimilated into the wider American society. These two books, with their extremely useful introductions and biographical notes, should help to raise awareness of the value and variety of American Yiddish poetry.

|