|

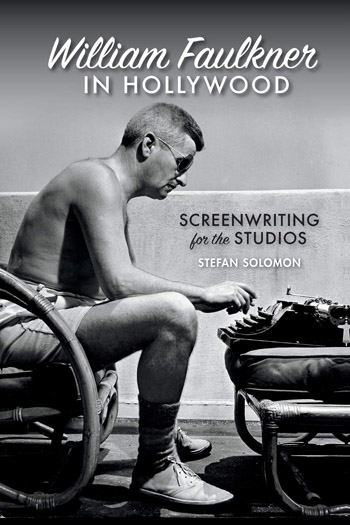

WILLIAM

FAULKNER IN HOLLYWOOD: SCREENWRITING FOR THE STUDIOS

By Stefan Solomon

The University of Georgia Press. 301 pages. £27.50. ISBN

978-0-8203-5789-8

Reviewed by Jim Burns

There was an assumption during the hey-day of the Hollywood studio

system that if a writer went to work there it automatically led to a

decline in his talents. The nature of writing for the screen meant

that all kinds of compromises had to be made, and that individuality

was much less important than the ability to work as part of a team

and accept that one had to function within the conventions that

applied in terms of producing a product likely to appeal to a wide

audience. There were restrictions placed on what could be dealt with

in a film, and how would-be controversial subjects could be

approached. Hollywood was an industry of sorts (writers clocked in

and clocked out as they would have done in a factory), turning out a

variety of goods, some of high quality, some not, and with the

profit motive frequently providing the basic reason for production.

Good work could, and often was, created within the system, but it

would be foolish to deny that a writer in Hollywood was often

employed on what can only be described as hack work. And writing was

only one part of making a film. Photography, music, direction,

acting, and other factors, were also of key importance. It was

probably true to say that, with only a few exceptions, writers were

not held in high-esteem by the studios. “Schmucks with Underwoods”

was Jack Warner’s opinion of the writers he employed.

A writer might have had an acknowledged reputation as a

novelist or playwright before arriving in Hollywood, but he or she

was only ever going to be seen as successful by the standards of

most the film community if they came up with the required scripts

for films that won awards and/or made money. There were producers,

directors, and others in Hollywood who respected

good writing, and tried to

support it, but they were few and far between.

Most writers went to Hollywood because the money was good. This may

have been especially true in the 1930s, when the Depression had hit

America hard and, unless a novel attained best-seller status, it was

difficult for authors to earn money from their books. Someone worth

referring to is Daniel Fuchs, who had published three critically

praised, but commercially unsuccessful novels (Summer

in Williamsburg, Homage to Blenholt, Low Company), plus stories

in the New Yorker and

elsewhere, and then decided that working in films might provide a

better way of supporting his family. I suppose it would be easy to

suggest that he is an example of a writer who failed to come up with

any writing of consequence after moving to the film capital, but it

would be an unfair judgement. A later short novel, and some stories,

demonstrate that he hadn’t completely turned his back on anything

other than screenwriting. But he seems to have adapted well to the

studio system and stayed on the West Coast for the rest of his life.

He was teamed with William Faulkner on at least one occasion.

Faulkner himself never pretended that he was in Hollywood for

anything but the money. Although a published novelist and

short-story writer, he had, at that point in the 1930s, not achieved

any sort of popular success. When the opportunity arose to earn

money as a screenwriter he appears to have seen it as a way to look

after his family and buy time to work on his novels. It’s obvious

that he would have preferred to have been at home rather than in

Hollywood. And it’s debatable how seriously he took the work he was

hred to carry out in the studios. Stefan Solomon sets out to show

how his contributions to various films were valued, and that the

practice of working on screenplays had an effect on Faulkner’s

writing in his novels. Because of the nature of writing for films

it’s often difficult to determine just where he contributed to a

script. He received on-screen credits for six films, and is said to

have been involved with around fifty in total. It’s worth quoting

what Faulkner himself once said: “I’m a motion-picture doctor. When

they find a section of a script they don’t like I rewrite it and

continue to rewrite it until they are satisfied. I reworked sections

in this picture. I

don’t write scripts. I don’t know enough about it”.

Opinions about how much Faulkner contributed to even the screenplays

where he received a credit are divided, as are those about how he

viewed his role as a Hollywood writer. When Howard Hawks directed

Land of the Pharaohs in

1955, the screenplay was credited to Faulkner, Harry Kurnitz, and a

relative newcomer, Harold Jack Bloom. Solomon notes that Faulkner

happily acknowledged that Kurnitz did much of the writing for the

film. And there are some instructive reminiscences by Bloom in Max

Wilk’s Schmucks with

Underwoods: Conversations with Hollywood’s Classic Screenwriters

(Applause Theatre and Cinema Books, New York, 2004) which throw

light on Faulkner’s general behaviour while on location in Italy.

Bloom’s opinion was that he viewed it as a holiday with pay and made

the most of little luxuries (wine, meals in expensive restaurants,

etc.) that could be added to the studio expense account. He also

thought that Faulkner was there because Howard Hawks, an old friend,

wanted him to be, and was conscious of having his name on the screen

credits as a matter of prestige. Faulkner’s reputation as a novelist

was beginning to flower by the mid-1950s. It perhaps needs to be

said that, whoever contributed what to

Land of the Pharaohs,

didn’t make a very good job of it. The writing was routine at best,

and the film notable only for its spectacle.

As for Faulkner’s attitude towards film-making in general, it

appears to be true that he didn’t hold it in high regard.

He must have been competent enough with what he did,

otherwise he wouldn’t have been kept on the studio payrolls for any

length of time. But it was just a job and a way of earning money,

and I think other writers, more attuned to the idea of screenwriting

as a profession with its own particular skills, recognised that

Faulkner didn’t have their sense of commitment to the practice.

Nunnally Johnson, a well-regarded writer and producer, said:

“Faulkner worked on a script for me once but I never thought for a

moment that he had the slightest interest in either that script or

anything else in Hollywood”.

And Harold Jack Bloom, who as noted earlier, had known and

talked with Faulkner, was of the opinion that: “He had no respect at

all for films. He didn’t consider anything about the movies as an

art form. He felt that doing anything in films was getting money for

nothing, and he certainly wanted the money”.

On the other hand, a talented director like Jean Renoir recalled

that Faulkner’s admittedly small contributions to the screenplay for

The Southerner were of

great value. And Howard

Hawks claimed that Faulkner “contributed enormously” to the making

of Land of the Pharaohs.

It’s amusing to read what Faulkner said of the film: “It’s the same

movie Howard has been making for 35 years. It’s

Red River all over again.

The Pharaoh is the cattle baron, his jewels are the cattle, and the

Nile is the Red River But the thing about Howard is, he knows it’s

the same movie, and he knows how to make it”.

The relationship with Howard Hawks is an interesting aspect of

Faulkner’s time in Hollywood, and five of the six films that earned

him on-screen credits were directed by Hawks:

Today We Live, 1933; The Road

to Glory, 1936; To Have and Have Not, 1944; The Big Sleep, 1946;

Land of the Pharaohs, 1955. The sixth,

Slave Ship, was directed

by Tay Garnett in 1938. It has to be accepted that Faulkner didn’t

have the only credit for any of these films, and various writers

shared recognition with him. For

Today We Live, for

example, he was credited for dialogue and the film having been based

on his short-story, “Turnabout”.

Slave Ship acknowledged

that he provided the story but others the screenplay. He was

credited with the screenplay of

The Road to Glory, though

with another writer, Joel Sayre. Jules Furthman accompanied him in

the credits for To Have and

Have Not and The Big

Sleep, with Leigh Brackett added to the latter’s credits. And we

know about Land of the

Pharaohs and its trio of writers.

Obviously, with several people involved and credited, and probably

others who tinkered with the screenplay as it was developed

(standard practice in Hollywood; Faulkner was one of six writers

employed on a film called

Country Lawyer, and at least one other

was later called in), it’s often difficult to ascertain who

wrote what. But Solomon’s diligent research work has unearthed some

documents that can be linked to Faulkner. And the discovery of the

“treatment” for Sutter’s Gold

(based on a novel by Blaise Cendrars) by another academic

enables Solomon to discuss Faulkner’s writing for Hollywood in

relation to two novels –

Absalom, Absalom! and

Pylon – to discover if there were any influences in either

direction. His comments may hold more relevance for students of

Faulkner’s literary works than those of film history, but they are

generally informative. It’s fascinating to note how he incorporated

“non-human sound” when writing for films as support for dialogue.

Faulkner may have been prone to say that the only aspects of cinema

that interested him were newsreels and Mickey Mouse, but he does

seem to have well-aware of the potential that the introduction of

sound offered once it was introduced into films.

If Faulkner had only six on-screen credits, but is reputed to have

worked on at least fifty films, it’s possible that some of what he

did made a difference to what are now considered lasting examples of

the range of films Hollywood

could turn out. We’re told that he contributed, in one way or

another, to Gunga Din,

Mildred Pierce, Drums Along the Mohawk, and

Stallion Road, to name

just a few of them. Stallion

Road was based on a novel by Stephen Longstreet, who was given

sole credit for the screenplay. But Faulkner had done the initial

adaptation of the novel, and Longstreet later said it was “a

magnificent thing, wild, wonderful, mad. Utterly impossible to be

made into the trite movie of the period. Bill had kept little but

the names and some of the situations of my novel and had gone off on

a Faulknerian tour of his own despairs, passions and story-telling”.

There were also films that Faulkner worked on but which were never

made. The Life and Death of a

Bomber, a projected wartime morale-booster, was one, and a

planned film about General De Gaulle another.

And, though

The Left Hand of God did

eventually appear, with Humphrey Bogart as its male lead, its

initial stages, on which Faulkner was employed, were interrupted

because of objections by the Hollywood censor, the Hays Office,

anticipating potential negative comments by the Roman Catholic

Church. The story involved someone disguising himself as a priest in

order to escape from the Japanese, and it was felt that it would be

unacceptable for him to be seen in the film as being involved any

sort of ceremony that he wasn’t qualified to conduct. The screenplay

for the released version of the film was written by Alfred Hayes, a

talented novelist whose My

Face for the World to See

and In Love are

rightly considered minor classics.

Having spent so much time at the cinema when I was young, and

continuing my interest in films since the 1940s¸ I was constantly

entertained and intrigued by what Solomon had to say. His passing

references to other writers that Faulkner teamed up with, if

sometimes only for a short time, caught my attention. He revised a

screenplay for God is My

Co-Pilot which had originally been written by Steve Fisher,

though in the end two other writers, Abel Finkel and Peter Milne,

were credited when the film was released. Fisher had a long career

in Hollywood, but was also a prolific writer of pulp novels, a

couple of which – I Wake Up

Screaming and No House

Limit – are still worth reading. I pointed to Daniel Fuchs

presence in Hollywood earlier in this review (he co-operated with

Faulkner on Background to

Danger, based on an Eric Ambler novel, with W.R. Burnett, a

popular crime novelist, getting

credit).

There were a couple of occasions when Faulkner might have come into

contact with the Hollywood Left of the 1940s, though he clearly had

no political affiliations himself in that direction. He had been one

of the group of writers, including Frank Gruber, Thomas Job, Robert

Rossen, and A.I.Bezzerides, working on a screenplay for

Northern Pursuit. It was

expected that Gruber and Rossen would receive acknowledgment for it,

but Rossen handed his credit to a fellow-communist, Alvah Bessie,

who needed on-screen recognition to secure his continued employment

in Hollywood. Solomon says that “Faulkner and Job seemed

particularly incensed by the closing of party ranks here, and Gruber

would later recall it as a ‘Communist conspiracy’ “. The Party link

cropped up again when Faulkner’s novel,

Intruder in the Dust, was

turned into a film in 1949. The screenplay was written by Ben

Maddow, who had a radical past and was blacklisted, but found a way

back into films when he agreed to name names later in the 1950s.

It’s not known if Faulkner had any input in the making of the film,

or if he had ever met Maddow.

I realise that I’m indulging myself by referring to other writers

and their publications, but the fact of work in Hollywood being a

collaborative effort does incline me to wonder how far Faulkner was

aware of his fellow-writers’ achievements?

Bezzerides had published a couple of novels (Thieves’

Market and The Long Haul,

both reprinted in recent years) and Frank Gruber was well-known for

his crime novels. And Harry Kurnitz, who I mentioned earlier in

connection with Land of the

Pharaohs, wrote plays, and several entertaining novels, one of

which, Invasion of Privacy,

mocked some of the pretensions associated with the film industry.

Solomon merely refers to him as a “young writer” but he was well

into his forties when he knew Faulkner and was already an

established-screenwriter with credits dating back to 1938.

William Faulkner in Hollywood

has much to recommend it to both students of the novelist's work and

those fascinated by the broad history of how screenwriters fared

within the Hollywood studios system. Stefan Solomon is informative

about how screenplays were produced and the problems that writers

faced when attempting to outline something worthwhile in the face of

demands to direct their work solely towards commercial success. He

writes clearly and objectively and although his evaluations of the

plots and characters of Faulkner’s novels might be aimed more at a

literary rather than film readership they are never less than direct

and instructive. The book operates on more than one level. It is

well-researched, has ample notes, and a useful bibliography. I think

it should be pointed out that there is little biographical

information about Faulkner in it, and anyone wanting details about

his private life, his battles with the bottle, and similar matters,

will need to look elsewhere. This is not a drawback to enjoyment of

Solomon’s book. His focus is on the work that Faulkner did in

California, and not what personal adventures, or misadventures, took

place there.

‘

|