|

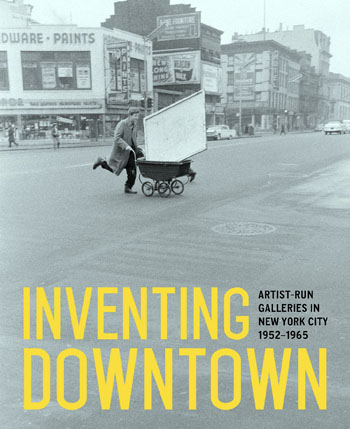

INVENTING DOWNTOWN: ARTIST-RUN GALLERIES IN NEW YORK CITY 1952-1965

By Melissa Rachleff

Prestel Publishing. 296 pages. £50. ISBN 978-3-7913-5558-0

Reviewed by Jim Burns

“Tenth Street,

the whole block on

Tenth Street

became the hangout. One hung out at the galleries and Friday nights

were big social occasions, and it got to be very much the Downtown

scene ……That world was very small then – a few hundred people”.

Al Held

In the 1950s in New York

it was Abstract Expressionism that held sway in the art world.

Newer, younger artists, and even some older ones, who perhaps leaned

more towards figurative painting, had difficulty in getting their

work shown in the established commercial galleries in uptown Manhattan. Without critical approval, and that

could only come when they exhibited, they weren’t likely to be asked

to provide paintings for consideration by dealers and others in

positions of power and influence.

It needs to be also acknowledged that, despite some attention being

paid to painters like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning, there

wasn’t widespread interest in contemporary art on the part of the

general public and the media. If people wanted to buy paintings they

mostly looked to the past, and often to European artists. A concern

for the new would come later, but in the early and mid-Fifties, even

in New York, working artists inhabited, as Al

Held recalled, a small world.

Faced with indifference from the public, likely patrons, and

critics, young painters and sculptors considered their position and,

in some cases, decided that opening their own galleries might not be

a bad idea. Their work would then be seen, if only by a small

audience of fellow-artists, and, hopefully, by a critic or two

curious enough to venture into what could be somewhat shabby and

run-down areas of downtown New York.

Harold Rosenberg, one of the leading writers on art, and a critic

who was partly responsible for promoting the so-called Action

Painters (another name for the Abstract Expressionists) wrote an

article for the Art News

Annual in 1954 in which he talked about “Tenth Street: A

Geography of Modern Art”. (reprinted in his

Discovering the Present:

Three Decades in Art, Culture, & Politics,

University

of Chicago Press,

1976). In it he described an area of pawnshops, liquor stores, cheap

restaurants, a poolroom, an employment agency for restaurant

workers. And, for the artists, cheap studios in old factories,

warehouses, shops, and other empty buildings.

There had been some attempts at drawing attention to new work by

young artists when certain coffee-house owners in

Greenwich Village hung paintings on their walls. But the

numbers and sizes of the selected canvases were inevitably limited

by the space available. Having their own galleries would obviously

provide better facilities for the artists. The aim was that the

galleries would be run on a co-operative basis, with members

donating a fixed amount each month to pay for rent, lighting, and

other necessities. Initially, artists would take turns looking after

the gallery concerned during opening hours. After a time, a regular

assistant might be hired, assuming that funds were available to pay

a modest wage.

Irving Sandler provides a vivid picture of the time he spent in such

a role at the Tanager Gallery in his

A Sweeper-Up After Artists: A

Memoir (Thames & Hudson, London, 2004), and also writes about

the need to accept that functioning in the Downtown milieu meant

acknowledging that poverty was a way of life, at least for a time.

It wasn’t that anyone wanted to be poor, and in fact, opening a

co-operative gallery was usually a means to an end. Most artists saw

“Downtown galleries as transitional. Nearly all the artists strove

for commercial representation uptown”. This shouldn’t be held

against them, and they weren’t all ready to compromise on their

ideas and ideals about art in order to succeed. But artists, most of

them, anyway, produce works that they want to be seen and sold, and

there was a better chance of that happening in the commercial

galleries.

The Tanager Gallery, which ran in one location or another (mostly 90

East Tenth Street), from 1952 until 1962, was “the most influential

of all the co-op galleries”. Other leading co-op galleries were the

Hansa (1952-1959) and the Brata (1957-1962), and all three helped to

“redefine the parameters of artmaking and challenged the definition

of art by critics and museum curators”.

It would take up too much space to list all the painters and

sculptors involved with these galleries, but among them were William

King, Angel Ippolito, Lois Dodd, Wolf Kahn, Jan Muller, Nicholas

Krushenick, and Al Held.

It was. on the whole, a male-dominated scene. Rosalyn

Drexler, asked about her experiences at the

Reuben

Gallery (1959-1961),

talked about being “aware that there were things that happened to

women”, meaning that their work was often looked on as less relevant

or interesting than that produced by men.

Each gallery had a distinctive approach to what was exhibited. The

Tanager’s “juxtaposition of disparate styles often defied logic”,

with “representational art alongside abstraction”. The City Gallery

(1958-1959), with Red Grooms and Jay Milder involved, focused on

“life in New York as a core

subject”. The March Group (1960-1962) was located at 95 East Tenth Street in “the basement,

a squat, cramped space with exposed pipes, tin ceiling, and

whitewashed brick walls”.

With artist Boris Lurie, photographer Sam Goodman, and

poet-artist Stanley Fisher participating, the exhibitions there were

heavily politicised. There are some of Lurie’s provocative collages

in the collection of poems and paintings,

Beat Coast East: An Anthology

of Rebellion (Excelsior Press, New York, 1960) that Fisher

edited.

Another significant outlet for experimental art was the Judson Gallery

(1959-1962), linked to “the progressive Judson Memorial

Church on Washington Square South”.

The gallery was in “an approximately 1,000 square feet room

in the basement of Judson House, an interracial student dormitory at

239 Thompson Street, around the corner

from the church”. Claes Oldenberg took over “programming for the

Judson”, “and arranged for a joint show with Jim Dine in November

1959 that featured new `figurative work inspired by the streets,

Brutalism, and children’s drawings”. The

Judson

Gallery also became a

centre for what became known as “Happenings”, forms of performance

art in which Oldenberg, Dine and Allan Kaprow were heavily involved.

It was an especially lively time for the church as a little

magazine, Exodus

(1959-1960), edited by

Bernard Scott and Daniel Wolf, was published from the gallery. Some

of Oldenberg’s pictorial work appeared in

Exodus, as did that by

Red Grooms and Richard O.Tyler. There was also prose from Ivan Karp,

who worked at the Hansa Gallery for a time and recalls its struggle

to survive in an interview in

Inventing Downtown. There are photographs by Fred McDarrah from

an event at the Judson Gallery

for a new issue of Exodus

in The Beat Scene, edited

by Elias Wilentz (Corinth Books, New York, 1960). It’s also worth

looking at McDarrah’s The

Artist’s World in Pictures (Dutton, New York, 1961), which has

material on the Tenth Street galleries.

It’s noted that another venture which took place at the Judson

Gallery was artist Phyllis Yampolski’s “Hall of Issues”(1961-1963),

described as a strategy for “merging art and politics”. It invited

anyone “who has any statement to make about any social, political or

aesthetic concern” to participate by displaying art work or poetry

or other forms of expression. It tapped into a growing need to say

something as the restrictive effects of the McCarthy Era wore off,

and what Melissa Rachleff, quoting Daniel Bell, refers to as the

“end of ideology”, struck a chord with many artists and writers.

But as she further notes: “Such openness promoted diversity,

but lack of a clearly defined political goal kept the project as an

art initiative diffuse, fractured, and ultimately uneven”.

The Hansa Gallery had stayed afloat largely due to the efforts of

Richard Bellamy, and when it finally closed he “drifted and looked

for a job”. Eventually, Ivan Karp introduced him to Robert Scull, a

wealthy businessman who was prepared to put up the money needed to

open an uptown gallery. The Green Gallery (1960-65) was the result,

and led to some of the Downtown artists moving uptown, something

that wasn’t always looked on kindly by those left behind. But Claes

Oldenberg was of the opinion that “The Green Gallery was a way to

feel at home on

Fifty-Seventh Street for the first time.

It was a very unpretentious place. The installations were very

straight ahead. There was nothing fancy about it; it was like the

downtown moving uptown”.

The full story of the Green Gallery and its backer, Robert Scull,

would provide material for a book in itself, with shady financial

dealings and much more to complicate the day-to-day operations of an

art gallery. Scull’s wife had a significant role in what happened:

“Ethel clearly had no patience for Bellamy’s personal conduct or

managerial style. And unlike her husband she did not find him

fascinatingly bohemian. It was only a matter of time before her

discontentment coupled with Bellamy’s disinterest in business and

her husband’s limited finances would come together and bring the

gallery to an end”.

Before it closed, Green Gallery had played a part in promoting the

work of James Rosenquist, Tom Wesselmann, and George Segal, all

three of them soon to become leading figures in the Pop Art

movement. The rise of Pop Art, its popularity with dealers and

collectors (if not initially with the critics), and with the public,

led to the boom in the art market that essentially started in the

1960s and continues. Leaving aside the question of money, and as

Rachleff notes, there is a “subservience to wealth at the heart of

most art enterprises”, there is no doubt that Pop Art gained a wide

audience. As the artist Lucas Samaras said, “the images were easily

assimilable by the whole country”. And the media liked to run

stories on the wealthy collectors who bought Pop Art and displayed

it in their homes. Samaras credits Robert Scull with helping to

further Pop Art by having it in his own house, and inviting other

wealthy people to view it “and see how nice it looked and think how

nice it would look in their house”.

It’s relevant to mention that the Downtown activity throughout the

1950s and early-1960s had often inter-related with the other arts,

such as poetry. Some galleries had poetry readings to help draw

attention to their exhibitions. It’s mentioned that: “Poetry

was integral to the creative life of the Lower East Side, where the main venues for readings in the

early 1960s were Le Metro, on

Second Avenue between Ninth and Tenth

Streets, and Le Deux Megots, on

East Seventh Street. The informality of

the café setting transformed Downtown poetry from a solitary

endeavour to a performative art”. There’s a photograph of Jack

Micheline, a socially-conscious poet sometimes associated with the

Beats but really out of an older bohemian tradition, reading at one

of Phyllis Yampolski’s “Hall of Issues” events. The black poet,

Amiri Baraka (formerly known as Leroi Jones) is acknowledged as a

leading light of the Spiral Group (1963-1965), a group of black

poets and painters discussed in

Inventing Downtown.

The accounts of the various galleries are fascinating to read, and

there were others besides those I’ve mentioned. The Reuben Gallery

(1959-1961) featured “anti-ceremonious, anti-formal, untidy,

highly-physical (but not highly permanent)” exhibitions which were

later credited with leading towards “Pop”. Some “iconic projects” by

Jim Dine, Claes Oldenberg, Allan Kaprow, and others took place at

the Reuben, and were designed to “shift away from traditional

artistic categories” and explore “space, performance, and process to

the hilt”. The Center (1962-1965) had Aldo Tambellini “working in

his building’s backyard”, and using found objects (pipes, joints,

discarded washbasins, beer cans) for his sculptures. He treated his

studio as “a community space”, and involved local people in what he

was doing.

That the period concerned was a vital one is made clear in

Inventing Downtown, but

it wasn’t all smooth sailing. There is some evidence that, by around

1960, the notion of co-operative-operated galleries was declining.

Financial limitations inevitably affected what could be done. And

there were clashes of temperament and egos. John Gruen, writing

about his time at the Hansa Gallery in

The Party’s Over Now:

Reminiscences of the Fifties – New York’s Artists, Writers,

Musicians, and their Friends (Viking, New York, 1972) had this

to say: “The Hansa group may have been compatible as far as art was

concerned, but not as regards its members personalities. As the

gallery began to function any number of violent personal clashes

took place, with hysterical outbursts by the more high-strung

artists. Countless decisions had to be voted on, and there was

always someone totally against one policy or another. Tempers

invariably ran high”.

I imagine that what happened at Hansa was probably similar to what

took place in other co-op galleries, especially the bigger ones,

where there were likely to be a variety of ideas and opinions about

personalities and policies.

Inventing Downtown mentions some disagreements, and there were

resignations from groups and bickering about who was to be included

in exhibitions.

Generally, however, there does seem to have been a great deal of

co-operation, and the interviews

in Inventing Downtown

do elicit some almost-wistful memories of a time when, poor and

un-recognised as they were,

the artists appeared to be relatively content. Wolf Kahn

claimed that “There was no frantic careerism in those days. It was

amazing how idealistic we were, and unself interested”.

Jim Dine remembered, “There was a kind of bohemia”.

Jean-Jacques Lebel thought that “Those years in New York felt like paradise. Art was life,

daily life was intense art”. And Irving Sandler reckoned that “Most

artists were living on air, and elegantly. I don’t know how they did

it…..Poverty had an upside. There wasn’t then the division between

the successful artists and the unsuccessful artists. It was an open

situation”.

Inventing Downtown

is an engrossing and informative book, wonderfully illustrated and

massively documented. It should be essential reading for anyone

interested in the New York

art scene of the 1950s and early-1960s. For those

lucky enough to be in the city, it accompanies an exhibition at the

Grey Art Gallery, New York University, which opened in January and

runs until 10th December, 2017. It then moves to the Kunstmuseum

Luzern,Lucerne, Switzerland

from 28th September, 2018 to 25th November, 2018.

|