|

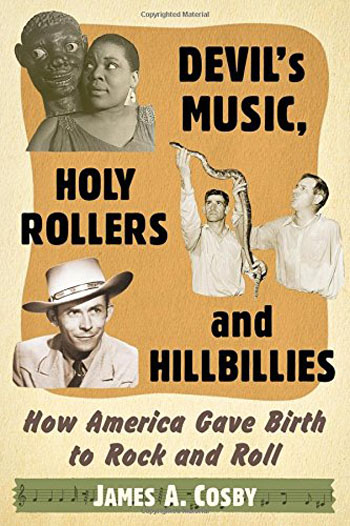

DEVIL’S MUSIC, HOLY ROLLERS AND HILLBILLIES: HOW AMERICA GAVE BIRTH TO ROCK AND ROLL By James A. Cosby McFarland & Co. 254 pages. $35.50. ISBN 978-1-4766-6229-9 (paperback) Reviewed by Jim Burns

What was the first rock and roll record? Some would say Jackie Brenston’s “Rocket 88,” others might opt for Wynonie Harris’s “Good Rockin’ Tonight.” A few might point to Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock,” perhaps because it was the record that probably attracted widespread attention to rock and roll. Brenston and Harris might have been popular with black listeners, and a smaller number of aware, younger whites, but Haley’s record could easily be heard on the radio, as I recall from my army days in Germany in the mid-1950s. I’m talking from an English point of view, and in the early to mid-1950s you weren’t likely to hear Brenston’s or Harris’s raunchy records on the BBC. I suspect the same might have been true of the major radio stations in America around that time. It needs to be said, however, that attempts to pin down the first rock and roll record are essentially doomed to failure, and not only because people will always disagree about it. Movements in music, as with other art forms like painting and literature, simply don’t start with a single item. It’s true that, at some point, a particular disc, painting, book, might well seem to represent a certain style. But there would have been earlier indications of where things were heading, and how they would shape what would eventually become a form that could be labelled. The roots of rock and roll can be found in a number of places, as James A. Cosby sets out to discover in Devil’s Music, Holy Rollers and Hillbillies. According to Cosby, the Pentecostal Church might well be “at the heart and soul of this whole history.” Members of this group were given the nickname of “holy rollers” because of their habit of being “slain in the spirit,” and writhing and rolling in the aisles. They sometimes babbled what seemed to be incoherently, and their actions were “fueled by an equally wild and emotional music, atypical religious instrumentation, and open-throated singing.” And, if Cosby is correct, the one person who might be said to link the “reeling and rocking” of the Pentecostals to rock and roll was Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Cosby describes her in a 1962 television programme as playing an electric guitar and “not simply singing the gospel – she is rocking the gospel.” Alongside the church music that blacks experienced, and which had been around for many years, there were the secular blues performers. Cosby firmly places the origins of the blues in the Delta, the area that he defines in this way: “The Mississippi River Delta (technically an alluvial plain) is the low- lying area between the Yazoo and Mississippi rivers, between Vicksburg, Mississippi to the South, and Memphis, Tennessee to the north, an area of some 6,000 square miles.” Known as having “some of the most fertile farm soil in the world,” it offered employment for both blacks (slaves prior to the Civil War, supposedly free after it) and poor whites. Cotton picking was a major occupation. Cosby quotes Robert Palmer’s description of the sound of the Delta blues: “The Mississippi Delta Blues musicians sang with unmatched intensity in a gritty, melodically circumscribed, highly ornamental style that was closer to field hollers than it was to other blues.” And he adds that Delta guitarists were deeply rooted in rural folk music. But I think it’s worth noting, too, that the notion of blues musicians playing some sort of simple, unalloyed style is probably often incorrect. It may have been that way in the early days, but “nineteenth century ballads, dance music of the time, as well as the up-tempo country blues,” all came within the framework of what bluesmen did when performing in clubs and bars. And once records and radios were easily available many different influences began to be absorbed into their music. Cosby refers to the legendary Robert Johnson as playing “all the pop hits of the day,” and says that Muddy Waters claimed that his influences were “as much Gene Autry and other mainstream fare, such as `Chattanooga Choo-Choo,’ as they were gut-bucket Delta blues.” It’s obvious that blues musicians would head for cities such as Memphis in search of employment, and so would inevitably broaden their musical experiences. Paralleling the blues was the music identified with poor whites in the South: “Country music’s roots reach back to the American colonists and a mix of English ballads combined with elements of Scottish reels, Irish jigs, and square dances (i.e. the poor man’s version of the French `cotillion’ and `quadrille’ ), along with strong influences from black culture.” And, though “the music was secular in nature,” it did take on “some of the religious themes and music of the Southern Protestant revival and camp meetings of the 1800s.” As with the blues, the guitar became a staple instrument for playing country music, though often with a fiddle and various rhythm instruments. Cosby points out that “country music, like the blues, was born out of a daily struggle for survival and its own tensions.” Despite the segregation that persisted in the South well into the twentieth century, it’s made clear by Cosby that many young white singers and musicians listened to their black counterparts and took lessons from them. Hank Williams “first learned guitar as a child from an African American street musician named Rufus Payne,” who “taught Williams the guitar basics, especially the blues and the importance of rhythm, both of which became crucial aspects of Williams’ country style.” Young whites could also tune in to the radio stations (often owned by white businessmen) that opened up in the South in the post-1945 period and were prepared to feature music aimed at a black audience. There they could hear records that white stations would never play. Cosby says that station WDIA in Memphis faced opposition from whites in the city who were “outraged to hear black Memphis coming through their radios.” Demands were made for the station to stop the programmes that highlighted black music, but the owners persisted. The programmes were popular and sponsors were presumably happy to pay to have their products advertised on them. The scene was being set for the advent of rock and roll. Black blues had evolved by this time into an urban form aimed at the many blacks who had moved to cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, New Orleans, and New York. With the guitars electrified and saxophones added the music, sometimes known as jump blues but perhaps more often as rhythm and blues, cut through the noise in clubs and bars, and the lyrics that singers like Roy Brown, Fats Domino, and Wynonie Harris hurled out were often full of references to drink and sex. I doubt that listeners to “Good Rockin’ Tonight” (recorded by both Brown and Harris) thought that it referred solely to having a good time on the dance floor. And interestingly one of Harris’s early-1950s popular records, “Bloodshot Eyes,” had its origins in a country and western hit by Hank Penny. Country music, too, had been changing and was increasingly referred to as country and western, with the groups expanding and some, like Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys, even providing a blend of country music and big-band swing. There was also the music known as hillbilly, a derogatory term usually applied to poor whites in the South. It was also sometimes referred to as honky tonk and Hank Williams recorded a track called “Honky Tonkin,” as if to proudly announce where he came from. Cosby explains that the name “was derived from the hard partying Southern bars of the same name, and the songs reflected a blue-collar lifestyle and edgier themes such as hard drinking, carousing, and loneliness.” It was largely due to Hank Williams and Ernest Tubbs, another country and western artist of the 40s and 50s, that honky tonk became popular. Soon, younger performers would transform it into early examples of rock and roll. What followed is, as they say, history, as Bill Haley took “Crazy, Man, Crazy” into the charts, Elvis Presley went into the Sun studio in Memphis and recorded “Hound Dog” and “Heartbreak Hotel,” and rockers like Jerry Lee Lewis (“Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On”), Carl Perkins (“Blue Suede Shoes”), and Little Richard (“Tutti Frutti”) stormed onto the airwaves and into theatres and clubs where they often created mayhem as a teenage audience responded to their music. Little Richard was black, and so was Fats Domino (“Ain’t That a Shame”), but most black artists, especially those linked to rhythm and blues, tended to be left behind and often drifted into near-obscurity as the 1950s progressed. Cosby says that some black performers were resentful at the way attention was focused on white singers and musicians, especially when they did cover versions of songs first introduced by black artists. Such records usually watered down the drive and energy evident in black performances, and in effect often neutralised any sexual content in them. Pat Boone singing “Tutti Frutti” and “Ain’t That a Shame” wasn’t a patch on Little Richard or Fats Domino, but as a clean-living white boy he perhaps persuaded parents that rock and roll could be respectable. I’ve given a quick history of the development of rock and roll, and James Cosby goes into a lot more detail about many of the singers he discusses. He’s also informative about the people in the background – the owners of radio stations, Sam Phillips of Sun Records, various disc-jockeys like Alan Freed who could feel the way the wind was blowing and were prepared to play rock and roll records on their shows. They were nearly all white in the early days, and it’s possible to argue that they saw a chance to make money but at the same time they helped promote a music that wasn’t popular in its initial stages. Had it been left to the major radio networks and record companies perhaps few people would have heard of Elvis Presley or Little Richard. That the majors quickly got on the bandwagon, once it became evident that there was a big market for rock and roll, shouldn’t surprise anyone. As well as a musical history of the 1940s and 1950s Cosby also provides a survey of the social factors that led to the rise of rock and roll. I don’t think he comes up with any new insights or observations, but what he says is of relevance. The conformity evident in certain areas of American society, with fears of communism, and a desire to get back to normality once the Second World War ended. combining to encourage people not to question the status quo, are outlined. And the prosperity of the 1950s had an effect as consumer goods occupied everyone’s attention. TV was spreading its influence in more way than one. Not everything was perfect, nor was everyone content with their lot, so there was more to the rise of rock and roll than just bored teenagers wanting an alternative to the often bland sounds of the acceptable (to their parents) popular music of the time. Devil’s Music, Holy Rollers, and Hillbillies is informative and entertaining and likely to appeal to anyone with an interest in popular music. I admit that my own tastes tend to run mostly to Hank Williams and his contemporaries, jazz, jump music, rhythm and blues, and the very early days of rock and roll. Cosby wonders at one point if making the music more accessible to a broader white audience changed it? I’ve always thought it did, and not necessarily for the better. But that’s a personal view. And I have to admit that I never could listen with pleasure to Elvis Presley. A couple of minor non-musical points. Cosby mentions the Harlem Renaissance and includes James Baldwin in a group of writers associated with it, but he surely came along some time later. Discussing the anti-communist activities of Joseph McCarthy, Cosby says that it was a “fellow congressman” who challenged him by saying, “Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?” But the records of the McCarthy-Army hearings show that it was Joseph Welch, a lawyer acting for the army, who spoke those words in response to McCarthy’s attempts to smear a young lawyer on Welch’s team for his past association with a suspect organisation.

|