|

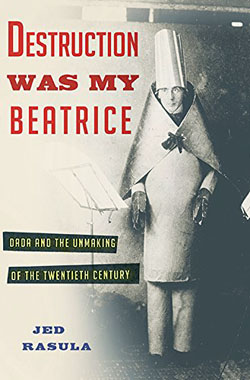

DESTRUCTION WAS MY BEATRICE: DADA AND THE UNMAKING OF THE TWENTIETH CENTURY By Jed Rasula Basic Books. 365 pages. £19.99/$29.99. ISBN 978-0-465-08996-3 Reviewed by Jim Burns

“For some, Dada was a mission; for others, it was no more than a convenient tool or weapon for advancing their own artistic ends.” I’ve quoted those words from Jed Rasula’s introduction to his engaging book about the lives and times of the Dadaists because it seems to me essential to bear them in mind when considering what Dada was and how it developed. Any movement, artistic, literary, political, involves people who are attracted to it for a variety of reasons. They come and go, perhaps add something, perhaps take something away. And at some point, the movement shifts and shades into something else. That’s what happened with Dada when it met Surrealism in Paris. Of course, some would argue that Dada never was a movement, as such. It might all depend on how you define a movement. Manifestos abounded among the Dadaists, but there wasn’t a clearcut programme in term of what they stood for. What they stood against might be easier to locate. But they were far too independently-minded as individuals to ever fully agree on a set of principles, and even if they had they would most likely have immediately disowned them. Dada was born in Zurich in 1916. I suppose that’s true enough, though qualifiers might need to be added in terms of earlier influences that affected the men and women who gathered at the Cabaret Voltaire in the Swiss capital. Did the Rumanians Tristan Tzara and Marcel Janco, for example, bring with them ideas that originated in the Jewish cafés of Bucharest? What was the effect of encountering Italian Futurism before the First World War? And what was known about Alfred Jarry’s work? His play, Ubu Roi, which is generally acknowledged as establishing the Theatre of the Absurd, surely provided a basis for at least some of the Dadaist activities. Rasula records that Hans Arp, one of the originators of Dada, was familiar with Jarry and performed scenes from Ubu Roi at the Cabaret Voltaire. The initial driving forces behind the founding of the cabaret were Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings. They had both left Germany on forged passports after taking part in anti-war protests. Hennings had, in fact been imprisoned for a time. Ball was said to have “a scholastic temperament,” but Rasula sums up Hennings in this way: “The world of the demimonde was more familiar to Hennings, who’d been a chanteuse on every kind of stage, from fashionable showcases to dives – with more of the latter. She’d taken lots of drugs and lived the kind of bohemian life that made her an easy target for charges of prostitution, and she had been arrested several times for petty crimes.” For some months the pair had worked with a travelling variety show (see Ball’s entertaining novel, Flametti, or the Dandyism of the Poor) with Ball, a competent pianist, providing musical accompaniment ranging from Chopin to popular songs. Back in Zurich, they contacted a retired Dutch sailor who owned a café in the bohemian district of the city. According to Rasula, “Ball pitched his notion of turning the place into an artists’ cabaret, and the intrigued owner consented.” It’s impossible not to wonder what the sailor thought once the cabaret got into full swing, but initially there didn’t seem to be a specified attempt to aim for anything outrageous or likely to offend. Ball’s advertisement in a local newspaper simply said: “Young artists of Zurich, whatever their orientation, are invited to come along with suggestions and contributions of all kinds.” On opening night, according to Rasula, “a contingent of Russian balalaika players” turned up, as did some locals who wanted to read their poems – “it was like an open mic today” – and more importantly, Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco, and Hans Arp put in an appearance. They would soon establish a rapport with Ball and Hennings and push the material performed at Cabaret Voltaire towards what we now identify as Dada. It needs to be stressed that all the major protagonists of the early days of Dada were exiles of one sort or another from the war that was engulfing Europe in 1916. As such, they saw their activities at the cabaret as a form of protest against the madness surrounding them. In particular they pointed to the corruption inherent in the way language was used to promote patriotism. Ball felt that “language itself was being poisoned,” and Rasula says that there “would be an aura of ghost dance religion in the nightly goings-on at the cabaret, as an air of exorcism, a ritual cleansing to purify a world mired in senseless slaughter.” Rasula is good at describing what actually took place on cabaret nights. This isn’t easy, because unlike present-day performances filmed or recorded evidence doesn’t exist. Some photographs were taken and these, together with memoirs by people who were present, have to suffice when it comes to trying to recreate the poetry readings, dances, and other aspects of a Dada evening. Rasula describes Richard Helsenbeck as reading his poems with “snarling aggression,” while “pounding on a drum and brandishing a riding whip or a cane.” What we really don’t know is how the majority of the audience reacted to such behaviour. Were they truly shocked? Or did they expect provocation and revel in it when it came? As Rasula says, “The performances ran the gauntlet, from tender ballads to raucous stomping,” and as there was an open-stage policy in operation all sorts of performers had an opportunity to show what they could do. Rasula refers to a Russian who read humorous pieces by Chekhov and sang folk tunes, and some students from Holland who pranced round with banjos and mandolins. Emmy Hennings, a key figure in the functioning of the evenings in Rasula’s view, was described by a Zurich paper as “the star of the cabaret.” There were other singers and some dancers from a nearby dance-school. I think the point to be taken from the range of material on offer is that it was a mixture and not just a sequence of Dada–inspired nonsense or sound poems and absurd sketches. Ball and Hennings left Zurich after a time and Tristan Tzara soon began to dominate the proceedings. A cabaret was all very well, but if it was to widen its influence Dada needed a magazine and other publications and, if possible, exhibition space. There’s an interesting comparison made by Rasula of the differences in character and temperament between Ball and Tzara. Ball was not a careerist, and “he had many interests ranging from politics to mysticism, with Dada tantalisingly dangling midway between the two.” Tzara, on the other hand, “felt there was nothing magical about Dada; it was simply a vocational opportunity, one that he tackled with the diligence of an aspiring law clerk.” That might seem a somewhat harsh summing up of Tzara, but it is probably a fact that without him and his talent for promotion, both of himself and Dada so that the two often appeared inseparable, the movement might never have become as notorious as it did. By 1917 the idea of Dada had spread to Berlin, largely thanks to Richard Huelsenbeck, who returned to the city early in 1917. War weariness was beginning to set in as casualty rates mounted, victory seemed far away, and food shortages hit the general public. Huelsenbeck’s view of his friends in the arts was that “None of us had much appreciation for the kind of courage it takes to get shot for the idea of a nation which is at best a cartel of pelt merchants and profiteers in leather, at worst a cultural association of psychopaths.” Huelsenbeck began to push the notion of the new man, “who transforms the polyhysteria of the age into a genuine understanding of all things and a healthy sensuality.” The snag was, as Rasula points out, that the idea of a “new man” could also be taken up by those on the right who saw him as “the pioneer of the storm” and a willing recruit into the ranks of the Freikorp when they smashed left-wing uprisings in the immediate post-war period. In Berlin some of those associated with Dada, like the artists John Heartfield and George Grosz, were soon also members of the German Communist Party. But others, such as Huelsenbeck and Raoul Hausmann, kept closer to the kind of attitudes evident in Zurich. A manifesto they distributed with the magazine, Der Dada, demanded that a Dadaist “simultaneous poem” should be the Communist state prayer, and all clergy and teachers should abide by the Dadaist articles of faith, though what those were wasn’t made clear, like so much else about Dada. Rasula tells us that the manifesto was reproduced in newspapers around Germany. Did anyone take it seriously? I somehow doubt it, though the thought of a few solid middle-class citizens huffing and puffing in indignation no doubt amused its authors. But in a country beset with hunger, massive inflation, violence on the streets, and other problems, it probably didn’t mean a thing to most people. Dada did, however, attract the attention of those who saw it as being as much of a threat as communism. In time, it would not be safe to have been associated with Dada. So-called Degenerate Art was a favourite target of the Nazis. Grosz and Heartfield eventually had to flee from Germany. Before moving on from Dada in Germany, where it didn’t last long, it’s interesting to mention the activities of Kurt Schwitters, a “natural born Dadaist,” according to Rasula, in relation to Dada. Based in Hanover, he seems to have run up against a certain amount of snobbish reactions from the Berlin Dadaists who looked on him as provincial and petite-bourgeois. Schwitters ploughed his own furrow, called his work Merz, and had little or no interest in politics, though he too had to leave Germany when Hitler came to power. While Tzara was still planning to move to Paris, and the Berlin Dadaists were reacting to the harsh social conditions in German, there had been some evidence of Dada activity in New York. In fact, it could be argued that there had been things happening in the city which may well have preceded the high jinks in Zurich. Marcel Duchamp had caused a fuss as early as 1913 when his Nude Descending a Staircase was included in the famous Armory Show and aroused responses that ranged from the outraged to the satirical. Later, Duchamp made the famous gesture of signing a urinal he bought from a shop and attempting to exhibit it as a ready-made or found object. Arguments are still heard about this, with some claiming that it led to the whole field of conceptual art and a consequent decline in drawing and painting skills. Picabia also spent time in New York, and Man Ray was there, along with characters like the eccentric Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, the provocative poet Mina Loy, and Arthur Cravan, whose “speciality was insulting artists.” Was there a New York Dada? Picabia was of the opinion that “New York is the Cubist, Futurist city; with its architecture, its life, its spirit, it expresses modern thought. You have skipped all the old schools and are Futurists in word, action and thought.” The Dadaists might have approved of skipping “all the old schools,” their manifestos often demanding the overthrow of the old, but there is something positive about Picabia’s comments that they probably wouldn’t have approved of, their own approach being essentially based on negativity. Destruction was “the characteristic expression of Dada.” It might also be worth referring to Man Ray’s reflections on whether or not there was Dada in New York: “There was no such thing. You can put me down as having said that. I don’t think the Americans could appreciate or enter into the spirit of Dada.” Tzara did eventually make his way to Paris where his arrival was eagerly anticipated by Breton, Soupault, Aragon, and other young writers and activists. Their initial reaction on meeting him was one of slight dismay. The “diminutive and unprepossessing figure” they encountered didn’t seem to go along with the man they’d imagined from his publications and letters. But, according to Rasula, Tzara soon convinced them of his talents as a public performer and publicist for Dada. The problem was that there was bound to be an eventual clash between Tzara and Breton, both men nursing a desire to be leader. There is an argument suggesting that Surrealism pre-dates or parallels Dadaism in some ways. The term was coined by Apollinaire in 1917, and Rasula says that “Surrealism was in the air long before it became formalised.” Tzara’s urge to be seen as head of the Dada movement led to him falling out with Picabia, with who he’d initially established friendly relations, Breton, and several more. Hans Arp called him Tzar Tristan, and another old companion from Zurich, Hans Richter, described him as “sensitive and aggressive, a magician with the alacrity of a weasel, arousing trust and suspicion” at one and the same time. There were Dada demonstrations and performances in Paris, some of which were greeted with the usual rowdy responses, much to the delight of the Dadaists, and others which fell flat. Also, “The Dadaists were getting restless, a bit bored with Dada.” Matters between Tzara and Breton came to a head when Tzara issued a statement saying, “Modernism is of no interest to me, and I think that it would be a mistake to say that Dadaism, cubism, and futurism rest on a common foundation. These latter two tendencies were based on the idea of intellectual or technical perfection above all, whereas Dada has never rested on any theory and has never been anything but a protest.” Breton reacted angrily, and put out his own press release which insultingly referred to Tzara as promoter of a “movement” from Zurich which “no longer corresponds to any reality.” Rasula rightly points out that “The Dadaists themselves were inconsistent practitioners of their own ism,” so they never really amounted to a movement. Dada did spread to individuals and small groups in other countries, though it made little headway in Russia and Poland, partly because Futurism had preceded it and “presaged many of the characteristics associated with Dada,” but also because politics got in the way of attempts to advance Dada ideas. It’s difficult to imagine Dada antics getting much of a friendly reaction in Russia once the Bolsheviks were in power. There were far more important things to attend to than listening to poets chanting meaningless phrases and insulting the audience. Avant-garde art and literature appeared to be a part of the process in the early days of the revolution, but it soon became obvious that artists and writers were expected to use their work to further the interests of the Party. Interestingly, Tzara did join the Communist Party in the 1930s, causing Hans Arp to comment: “Some old friends from the days of the Dada campaign, who always fought for dreams and freedom are now disgustingly preoccupied with class-aims and busy making over the Hegelian dialectic into a hurdy-gurdy tune.” Later, the old acquaintances of the Dada days in Zurich would bicker about who first came up with Dada as a name for their group. When the American artist, Robert Motherwell compiled his large book, The Dada Painters and Poets, in 1950, he had to contend with Tzara and Huelsenbeck each threatening to withdraw their contribution if the other was involved. What Hugo Ball, who had died many years earlier, would have made of such childish behaviour can only be imagined. Jed Rasula has written a lively, detailed history of Dada which also includes much useful information about other movements, such as Futurism, Surrealism, and Constructivism. He refer to numerous individuals and publications, and generally succeeds in re-creating some of the sense of excitement, and fun, that the Dadaists experienced during their brief moment in the limelight. Did they have a long-lasting effect? Rasula thinks they did and refers to various artists, pop musicians, and others who he suggests display elements of Dadaism in their work. It’s worth quoting some of what he says: “Dada’s recognition of the inherent artistic potential of rubbish and clutter, wreckage and chaos has had an enduring impact on subsequent artwork in every medium. As the twentieth century wore on, the iconoclastic animation of Dada would make it a vital source of inspiration for artists of all stripes. Far from being strictly a medium of destruction, Dada proved itself capable of being an inspiration, a progressive force.” Some critics will inevitably disagree vehemently with Rasula’s opinions, and there’s no doubt that an awful lot of mediocre and frankly bad work has been created by those who are believed to have taken Dada as their guiding light. Rasula isn’t blind to this fact, and commenting on a claim by Greil Marcus that punk rock had a “Dada paternity,” he asks, “but is every seething, indignant amateur a latent Dadaist? Can any sort of dissidence be tallied up on the balance sheet of Dada?” These are relevant questions and Rasula is right to ask them.

|