|

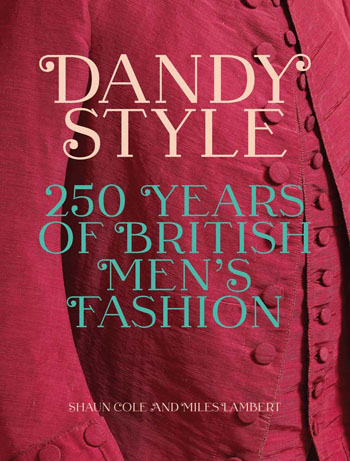

DANDY STYLE : 250 YEARS OF BRITISH MEN’S FASHION

Manchester City Art Gallery 7th October 2022 to 1st

May 2023

Reviewed by Jim Burns

Coming from a time when dark colours were, on the whole, the

acknowledged pattern for men’s clothing, and not being a dedicated

follower of fashion, I won’t pretend that I’ve ever taken a great

deal of interest in what was in and what was out when it came to

what to wear. I perhaps made a gesture towards it when, as a young

bebop enthusiast in the early 1950s, I wore a drape suit in

imitation of the American musicians pictured in the

Melody Maker and

Jazz Journal. But the

army grabbed me in 1954 and when I came out in 1957 bohemianism was

very much in the air. I can’t say that I ever took to the modes of

dress associated with beatniks and the like. It seemed easier to

wear conventional trousers and jackets if I wanted to hold down jobs

and not be denied entry to pubs. I had the experience of being with

a couple I knew who did look like beatniks and seeing them refused

service while the landlord quite happily asked me what I would like

to drink.

These thoughts occurred to me as I wandered through the exhibition

in Manchester City Art Gallery. It essentially kicks off around the

time of Beau Brummell and his associates and demonstrates how their

way of wearing clothes was a reaction to the more-ornate and

colourful styles that had preceded them. The Macaronis with their

tall powdered-wigs and high-heeled shoes lent themselves to being

caricatured, and they were by Cruickshank and others. There is a

very fine book, Pretty

Gentlemen: Macaroni Men and the Eighteenth Century Fashion World

by Peter McNeil (Yale University Press, 2018), which explores the

activities of the Macaronis and shows them to be more complex, both

sartorially and socially, than a simple dismissal of social

privilege and affectation would imply.

The dandies could likewise be caricatured even if what they wore

seemed restrained in comparison to the Macaronis.

Looking at the enlarged

portrait of Brummell which adorns a wall in the gallery reminded me

that not everyone admired the dandies. There is a chapter in Ellen

Moers’ classic study, The

Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm (Secker & Warburg, 1960) which

discusses the reaction from writers like Thackeray and Carlyle to

what the dandies represented. She says 1830 was the year “to

renounce the Regency and vilify the dandy class”. And she adds that

the growing “utilitarian middle-class” saw the dandy as “the epitome

of selfish irresponsibility…..the rising majority called for

equality, responsibility, energy; the dandy stood for superiority,

irresponsibility, inactivity”.

If a copy of the original can be found it’s worth looking at Bulwer

Lytton’s novel, Pelham or the

Adventures of a Gentleman, originally published in 1828 and

celebrated as “the hornbook of dandyism”, to see what caused Carlyle

to fulminate against it in his

Sartor Resartus.

In later

editions Bulwer, anxious to protect his reputation for sobriety in

the more strait-laced and morally-disapproving Victorian period,

edited out some of the descriptive passages about dandy idleness,

self-centredness, and concerns for the way one’s cravat was folded.

There were no doubt plenty of Victorians who nodded knowingly and

even approvingly when they heard that Brummell, after years of exile

in France, had died poverty-stricken, dirty, diseased and insane.

Moers goes on to say that “Distressingly personal in England, the

dandy ideal in France could become an abstraction, a refinement of

intellectual rebellion”. Writers like Baudelaire and Barbey

d’Aurevilly thought of the dandy in that way. And much later Albert

Camus included them in his book,

The Rebel: “The dandy is,

by occupation, always in opposition”.

Should anyone want to

read what Barbey

d’Aurevilly said about the dandy rebellion, a translation of his

essay is included in George Walden’s

Who is a Dandy? (Gibson

Square Books, 2002). Walden himself has useful things to say : “Yet

clothes, it can never be stressed enough, are merely the outward

sign of an inner disposition. True dandyism, aristocratic or

pseudo-proletarian, is a philosophy. This need not imply a highly

intellectual view of the world”.

By following a personal preoccupation with Brummell

I’ve drifted away from the exhibition. But it had its effect by

persuading me to get out some books and think about the dandies.

Walden’s book, referred to earlier, relates them to our own times

and current obsessions with celebrities, self, and how we look. The

excesses and refinements of male dress that became evident in the

1960s (in some cases almost back to the Macaronis) are on display in

Dandy Style. It’s an

informative exhibition, with paintings (Gainsborough, Thomas

Lawrence, Hockney) and photographs to accompany the clothes. Even if

the philosophical base for dandyism (if there is one) doesn’t

interest you it’s fascinating to see what men have chosen to wear

since Beau Brummell made his innovative alterations to how they

should dress.

|