|

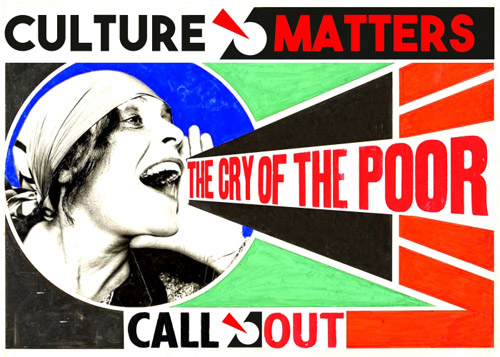

THE

CRY OF THE POOR

Selected and edited by Fran Lock

Culture Matters

In December 2019 the poor had a choice between Boris Johnson or

Jeremy Corbyn. In Barrow, Leigh and Grimsby, to select only three,

they chose the Tory. These are by no means wealthy towns and

elections aren’t won there without garnering a fair proportion of

the votes of the poor. The puzzle is: why has democracy ie,

essentially, universal suffrage and parliamentary representation

failed not only to replace capitalism but to eliminate or seriously

attenuate poverty?

The introduction to this anthology of poetry and prose is called

What Is Poverty and Who Are “The Poor”? Fran Lock

provides no definition of either but does claim that “the middle

classes have all the wealth”. Wealth and income are different. To

take the latter first, the bottom fifty percent of

full-time employees earn between the minimum wage and about

£30,000 a year, an income which barely takes you to the edge of the

middle-class. Ninety percent of employees earn between the minimum

wage and about £50,000 a year, which raise the question: why not a

hundred percent? The important point, however, is that it’s when you

hit the top ten per cent that incomes start to take off, but the

astronomical rise doesn’t happen till you reach the top one percent.

The richest one thousand people in Britain are worth beyond £500

billion. The top fifth have 40% of income. The bottom fifth, 8%. The

fourth fifth, 23% and the next to the bottom fifth, 13%. The top 10%

own 44% of the wealth. The bottom 50%, 9%, the same figure for the

richest 0.1%. There is, of course, significant regional variation:

in the south east the median wealth is £387,400 and in the

north-west, £165,200, largely a reflection of house prices.

Figures may seem rather cold and unromantic but they matter because

if we are going find a democratic means of eliminating poverty, we

will have to convince most of those people in the third fifth of

income, those with 17% of the income, that it’s not in their

interest to vote with the 0.1% who own as much wealth as the bottom

50%, and we aren’t remotely near doing so. As matter of fact, even

people in the bottom fifth who share five times less income than the

top fifth, still vote with the rich.

However, you look at it, this is a colossal failure of the left.

The contributions to this timely book are sympathetic to the poor,

but so was Iain Duncan Smith when he devised Universal Credit. It’s

important to grasp that Duncan Smith was genuinely sympathetic, he

just happens to be stuck up an ideological drainpipe which prevents

him seeing that capitalism is the problem. Capitalism, of course, in

all its forms. The USSR was marked by vast inequalities of wealth

and income, so is China and Castro was, by any standards, a rich

man. If we are going to get rid of poverty, we have to be

hard-headed about what it is, what causes it and how it can be

remedied

In 1938, in a review of Workers’ Front by Fenner Brockway,

George Orwell wrote: “In all western countries there now exists a

huge middle class whose interests are identical with those of the

proletariat but which is quite unaware of this fact and usually

sides with its capitalist enemy in moments of crisis.” The middle

class is bigger today but still behaves in the same way. No one has

done more to explain why than Noam Chomsky. It is manufactured

consent which is our enemy and we need to understand how that works

and how to combat it if we are going to persuade most teachers,

social workers, nurses, legal aid lawyers, bank clerks, call centre

supervisors and so on not to vote for the parties which look after

the rich (which today, of course, includes Labour). That parenthesis

shows just how dire our situation is.

Chomsky has been at pains over decades to point up the nefarious

role of intellectuals in propping up capitalism. The language of the

left and the thinking that goes along with it was forged in the

nineteenth century and the intellectuals responsible never asked how

radical change could be brought about through the ballot box. There

was no ballot and their assumption was violent uprising would do the

work. That’s one of the things which makes the old language utterly

useless. Mention “the ruling class” today and no one thinks of Paul

McCartney and Victoria Beckham, but they have vast wealth which they

invest and the people who manage the investments have more power

over government policy than the voters. Democracy is being bought by

the super-rich and it is the only means we have of bringing about

change. The responsibility of intellectuals who want capitalism

replaced by a co-operative, egalitarian economy is to produce a

language which hits home to the majority. If the bottom fifty

percent who own 9% of the wealth vote for change, it will come.

The book is divided into five sections so the contributions are

under a particular rubric. The first, about daily life, includes a

sixteen-line poem by Neil Fulwood, Estate. Its six-times

repeated refrain, “this is not a symbol” refers to both the general

way of thinking and the poetic use of images. Its point is that the

decay, decline and neglect it evokes is everyday reality. The poem

touches on the mess that is externalised language and the difficulty

of using it to evoke pity for the oppressed. It is redolent of

Brecht’s: when I say how things are, everyone’s heart must

be torn to shreds. Brecht was on the edge of despair because he

realised his words didn’t have the effect he anticipated. Much of

the writing here is trying to stimulate pity for the poor. One of

the most successful pieces is Thomas McColl’s short poem The

Chalk Fairy from the section about home and homelessness. What

makes it work is that it reaches the reader in the poem not through

it and its wit and slightly black humour are uplifting.

David Hume, like his friend Adam Smith, believed there was a natural

sympathy between people which is what makes us respond to others’

distress even when we have nothing to gain. The curious thing is,

this sympathy can easily turn into its opposite when people feel it

is being played upon. McColl gets round that difficulty deftly.

Tiffany Anne Tondut in Gale from the same section also makes

interesting use of the page to prevent her poem about loss of home

being too much of a button-holing. Martin Hayes does something

similar in the employed poor from the section on work. The

layout of his poem mirrors the collapsing lives of those he writes

about. Hayes is at his best in his work about the courier industry

where he has been employed for decades. Like his companion poet Fred

Voss, he has made the workplace poem his genre. His approach is

often full of witty disdain for bosses and jaded exasperation at the

sheer stupidity of management. Here, focussing on the problems of

people in work but hardly getting by, he intelligently employs the

visual effect of the poem on the page so the reader doesn’t feel

like the charity box is being shaken in front of them.

Edward Mackinnon’s Laughing at Poverty employs his usual

astuteness. He enumerates some of the pains the poor must endure,

but pulls away into disabused reflection on the culture which keeps

them impoverished:

All this, undeniably, is laughable:

The poem is psychologically accurate: graveside laughter is

engendered by the ludicrous system of injustice and the lies which

keep it in place. It is also clever in the way it refers the plight

of the poor to the poet’s reactions, rather than seeking to summon

up someone else’s pity.

The work section begins with a fine poem by Owen Gallagher,

Clocking Out. In four stanzas it tells the story of Owenie who

put his work clothes on the conveyor belt and walked out of the

factory, his own version of early retirement:

His backdoor’s

It’s a small act of rebellion à la Smallcreep’s Day, and

raises the important matter of our personal responsibility. Owenie

stages a personal revolution like Fred Voss who, four decades and

more ago, gave up a potential career as a Professor of literature to

work on the shop floor. Like the Orwell of Down and Out and

The Road to Wigan Pier, Voss wanted to write about the lives

of the people at the bottom from the inside. Orwell made an

interesting comment: his experience at private school and as a

colonial policeman left him with the sense that any success, even

the most modest, was a form of hypocrisy while the world was set up

for injustice. He ruined his health and shortened his life by

turning his back on the easy opportunities which could have come his

way. In a letter of 1939, he admitted to being penniless. He was

thirty-six and had published five books. His point is pertinent: if

we seek the best we can from the existing circumstances, how are

they going to change? There has to be a willingness to fail in the

terms the system offers, Phds, professorships, writing fellowships,

nice salaries and big houses, or our pleas for change ring hollow.

If the people at the bottom see those above them doing the best for

themselves, why shouldn’t they try to do the same? It isn’t serious

for the comfortable to call on the poor to revolt. Some lack of

comfort has to be the price of change for justice.

Caroline Maldonado’s Furlough.Florence.1629, reminds us that

radical inequality has long been with us. It’s an important

perspective because the kind of faith expressed by Bertrand Russell

in his Power: A New Social Analysis of 1939 that

tyrannies don’t endure is undermined by the continuation of

injustice over centuries. In addition, the twentieth century brought

us what humanity had never seen; previous despotisms weren’t

totalitarian. Nazi Germany, the USSR, today’s North Korea, these are

examples of a new kind of tyranny which may make Russell’s

conviction naïve. As democracy is shrunk bit by bit, we may be

heading for tyrannies of stasis in which the capacity of the rich to

deceive the rest is entrenched enough to bring a new Middle Ages.

There is no question about the urgency of the issue at the heart of

this book. It is heartening that so many writers are willing to

stand up for the poor. What we need also, of course, is serious

thinking and clear expression of how we can get out of the trap we

have fallen into. Hopefully some of the work in this book can

inspire it.

|