|

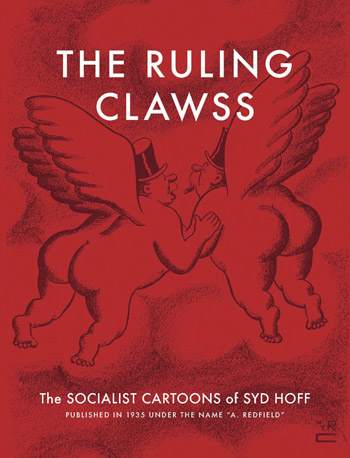

THE RULING CLAWSS : THE SOCIALIST CARTOONS OF SYD HOFF

New York Review of Books. 181pages. ISBN 978-1-68137-741-4

Introduction by Philip Nel

COMRADES IN ART : REVOLUTIONARY ART IN AMERICA 1926-1938

By Francis Booth

Independently published. 483 pages. ISBN 978-1-070-632698

Reviewed by Jim Burns

I’ve put these books, one new, one older, together because they both

deal with aspects of American art in the interwar years. In fact,

though I’ve referred to The

Ruling Clawss as “new”, it’s actually a reprint of a book

originally published by the

Daily Worker in New York in 1935. And the name on the cover

wasn’t “Hoff” but “A. Redfield”. It wasn’t unusual in those days for

contributors to communist publications like the

Daily Worker and

New Masses to use a

different name, especially if they also wrote for or illustrated

well-known, non-communist magazines and newspapers. Syd Hoff’s

cartoons appeared in the New

Yorker and elsewhere so he had every reason to differentiate his

political work, which probably didn’t pay much, from that he did for

publications which could offer higher fees. Being known as a

communist or communist-sympathiser would have been enough to get him

“blacklisted” in certain circles.

It’s easy to see why that would have been the case.

The cartoons are often satirical in their portrayals of the

rich and powerful. But the satire isn’t subtle, on the whole.

Bloated businessmen sit complacently contemplating laying off

workers or evicting families. Their overdressed wives idle the time

away while spoiling their sons and daughters and treating their pets

better than their servants. Bosses are seen to be in league with

judges and police in restricting union action. And the police, for

their part, are shown as thuggish and only too happy to break up a

picket line. “God, what a day,” says the policeman arriving home,

“I’ve been clubbing strikers for eight hours”.

I suppose it could be said that cartoons like these were essentially

aimed at the already converted. Or they were presumed to appeal to

the workers who, the Communist Party hoped, would read the

Daily Worker and

New Masses. I wonder how

many did? I’d guess that

more people were familiar with Hoff’s non-political drawings for

capitalist newspapers and magazines than with those in left-wing

publications. The 1935 appearance of

The Ruling Clawss may

have marked the high point of Hoff’s work as A. Redfield, though he

did continue using the name until around 1940. It’s interesting to

speculate whether the change in Party policy which led to the

closure of the proletarian-angled John Reed Clubs, and a move

towards a Popular Front which aimed to incorporate the middle-class

and place greater emphasis on intellectual activities, might not

have been the cause of the cruder class elements in Redfield’s

cartoons being played down.

Hoff certainly backed away from his earlier socialist sympathies

when interviewed by the FBI in 1952. He had, by that time, become

widely popular with syndicated comic strips, children’s books, and

other similar material published under his real name. He said: “My

association with the Daily

Worker and New Masses,

the Young Communist League and the American League against War and

Fascism was all based….on a lack of knowledge or experience as to

what they actually stood for”. And he added: “I do not now or did

not in the past at any time espouse the doctrine of Communism as I

now know it”. It may well be true that while the Redfield cartoons

lampoon the rich, criticise the police, and generally offer a bleak

look at capitalist society, they rarely directly advocate communism.

There is one illustration which shows two affluent women watching a

demonstration with marchers holding a banner reading “Towards Soviet

America”, but little else like it.

If Hoff’s activities are relatively easy to trace the same can

hardly be said of many of the artists listed in

Comrades in Art. This is

a curious book. It was published independently in 2012, with the

author, Francis Booth, presumably having a personal interest in

pointing out that most of the artists he covers are now forgotten.

He seems to ascribe this to the fact that abstract art, particularly

in the form of abstract expressionism, took over in the post-war

years, and social-realism went out of fashion: “History is written

by the winners and art history is no exception. The winners in

America’s history of art are the abstract painters who, subsidised

by the CIA from the early 1940s, showed the world the avant-garde

art American democracy and freedom could produce. The losers were

the artists working in the figurative tradition, who were seen from

then as old-fashioned and derivative. And the artists who had

political leanings have been virtually erased from the story of

American art. I would like to try to put them back”.

There are arguments that could be advanced against Booth’s version

of what happened, and he’s inaccurate in saying that the CIA

subsidised abstract art from the early 1940s. The CIA didn’t exist

until post-1945. Perhaps he meant to write “from the early 1950s”,

when the CIA certainly was active in backing publications like

Encounter and

Partisan Review and

supporting exhibitions of abstract art. Leaving that aside, what

does interest me, and where I agree with Booth, is his assertion

that many artists with “political leanings have been virtually

erased from the story of American art”. To my mind, his book has

value for the light it throws on some obscure artists who, in the

period he deals with, tried to create forms of art that could

incorporate social criticism and commentary while maintaining

standards of skill and creativity.

They weren’t all cartoonists producing sketches of the

well-fed and the wealthy and skewering their pretensions.

Stuart Davis is an example of a painter who allied himself with the

Left, but who never reduced his work to slogans. His “In a Florida

Auto Camp” from a 1926 issue of

New Masses has social

content but is not propaganda. And other illustrations are

near-Cubist, something that might not have found favour with a

dogmatic Party man like Mike Gold had it not been for Davis

left-leaning politically.

Artists had to be careful if they wanted Party approval. Otto

Soglow, for example, was “a clear example of how the revolutionary

artist who has not yet reached a sufficiently high ideological

political level proves incapable of embodying in his creation the

dialectical unity of the part with the whole, how he concentrates

the whole fire of his critique on isolated phenomena of the

capitalist system without showing their connection with the system

as a whole”. Booth says that those comments by a Russian critic

caused Mike Gold to drop Soglow from the pages of

New Masses. It perhaps

didn’t bother Soglow too much. He had a successful career as a

cartoonist for large-circulation newspapers.

An artist whose work I like very much is Reginald Marsh whose 1932

“Bread Line – No-One Has Starved” is a classic work from the period.

Marsh was not overtly political in his art, and much of it is a form

of idiosyncratic social comment. In some ways he’s descended from

the Ashcan School of artists (John Sloan, William Glackens, and

others), with a focus on recording the everyday urban lives of

ordinary people. He’s

certainly not forgotten. A large book,

Swing Time: Reginald Marsh

and Thirties New York (New York Historical Society, New York,

2012) published to

accompany an exhibition of the same name, is a wonderful evocation

of bars, cinemas, theatres, street corners, shops, subways, and much

else that made up city life at that time.

William Gropper was one of the most active artists in the left-wing

press, and his “Graduation Day” from

New Masses is worth

noting. It focuses on white collar workers waiting gloomily in an

employment agency, presumably knowing that there will be few, if

any, job vacancies available. And if there are they will be

low-grade and poorly paid. I was reminded of a poem from 1934

published in the first issue of

Partisan Review. Alfred

Hayes’ “In a Coffee Pot” is about the plight of the unemployed who

are over-educated for the jobs they may get : “The bright boys,

where are they now?/Fernando, handsome wop who led us all/The orator

in the assembly hall/Arista man the school’s big brain/He’s bus boy

in an eat quick joint/At seven per week twelve hours a day/ His eyes

are filled with my own pain/His life like mine is thrown away”.

Hayes also wrote the poem “ I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night”

which was set to music and recorded by Paul Robeson and other

singers with left-wing affiliations. Later, after the Second World

War, he was better known as a novelist and Hollywood screenwriter

and seemed to have left his radical past behind him. As he said in a

poem: “But who remembers now/The volunteers to Spain?/Or how the

miners stood/Sullen and angry men/In Lawrenceville in the rain?”

There are a few other artists who, if named, could evoke a response.

Rockwell Kent and Art Young might be among them, though in Young’s

case it could be that only

left-wingers would be likely to know his work. But what of

Fred Ellis, Mabel Dwight (her lithographs have power), Louis

Lozowick – a superb illustrator of industrial scenes, the samples of

his work are especially impressive – Joe Jones (a muralist), Peggy

Bacon, Jacob Burck, who did striking covers for

New Masses, and

Dan Rico with what

look like well-made, eye-catching wood engravings?

I’ve pulled just a few

names from a list of around forty that Booth provides. It's

sometimes possible to find out a little more about a few of the

artists, what happened to them when the Left collapsed in America,

and so on. How many of them were, like Syd Hoff, visited by the FBI

and asked about their earlier involvements?

But essentially they’re now

mostly forgotten.

As I said earlier, Comrades

in Art is something of a curiosity in terms of its publication

history. As well as discussing individual artists it has information

about the debates within communist circles in both America and

Russia concerning the nature and requirements of proletarian art,

social or socialist realism, and similar matters. Information is

given about the critics, again both American (Malcolm Cowley, James

T. Farrell, Waldo Frank, Joseph Freeman) and Russian, who might be

said to have set the pace for approaches to art by artists and their

potential audiences. There is a lengthy bibliography.

While writing this review, and I admit that it was largely done to

draw attention to Booth’s book, as well as to highlight the

appearance of a new edition of

The Ruling Clawss, I had

occasion to consult several other publications:

Artists on the Left: American Artists and the Communist Movement,

1926-1956

by Andrew Hemingway. Yale University Press, New Haven, 2002.

American Expressionism : Art and Social Change 1920-1950

by Bram Dijkstra. Harris & Abrams, New York, 2003.

Radical Art: Printmaking and the Left in 1930s New York

by Helen Langa. University of California Press, Berkeley, 2004.

Exiles from a Future Time: The Forging of the Mid-Twentieth Century

Literary Left

by Alan M. Wald. The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel

Hill, 2002.

|