|

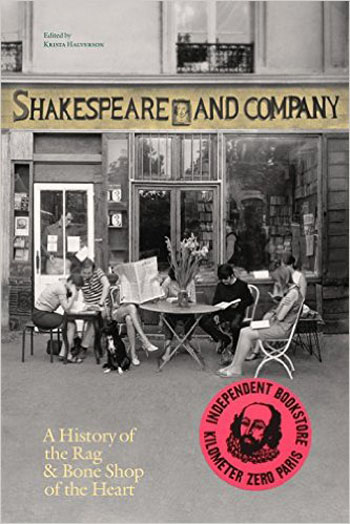

BROWSE: THE WORLD IN BOOKSHOPS Edited by Henry Hitchings Pushkin Press. 253 pages. £12.99. ISBN 978-1-782272-12-0 SHAKESPEARE AND COMPANY: A HISTORY OF THE RAG & BONE SHOP OF THE HEART Edited by Krista Halverson Shakespeare and Company. 384 pages. 35 Euros. ISBN 979-10-96101-00-9 Reviewed by Jim Burns

I’ve spent half of my life in bookshops of one kind or another, and even now, when bookshops seem to be in general decline, I like to find the ones that still manage to hang on in the face of competition from on-line sellers of both new and old books, and the seeming indifference of the general public. Whenever I arrive in a location I’ve not visited before the first question I ask is, “Is there a bookshop in town?” A second-hand one preferably, but a Waterstones, if necessary. There rarely is anywhere else for new books unless it’s a Waterstones. Blackwells in a university town, perhaps. I’m not complaining. It’s good to find any kind of bookshop still open. I prefer the second-hand shops because they’re where I might find something unusual. And they do still exist, I’m happy to say, though the quirkiness of their owners sometimes appears to work against their continuing for much longer. I was in Oldham recently and called at a little bookshop I’d visited some years ago. It was still there, but shuttered up, though books could be seen piled against an upstairs window. An enquiry at the premises next door elicited the information that the bookseller does still occasionally open his shop, though not on any sort of regular basis. He may be there if you call, he may not. Maybe it’s his age that now determines the opening hours? I knew the bookseller about forty years ago when we were both involved with the IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) and if he’s approaching my age he probably doesn’t find it congenial to his health to spend too long in the unheated shop tucked away in a little side-street. A bookseller in Manchester appears to spend much of his time in the café that you have to pass through to get to the bookshop. He’s cheerful enough, but doesn’t give the impression that he’s all that concerned about selling any books, many of which are badly overpriced. He’d surely sell more if he reduced his prices. What’s the point of having thousands of books simply gathering dust? A shop I went to in Cheltenham recently had a sign saying that all the books were half the marked prices. And I bought some. But the man in Manchester steadfastly holds to his principles. I can’t help suspecting that the shop is a good reason for not going home, if he has one. It wouldn’t surprise me to learn that he sleeps on the premises. Still, he runs a bookshop so, again, I shouldn’t complain. The oddball nature of many of the characters in the second-hand book trade is a feature of Iain Sinclair’s lively piece in Browse about a now-defunct shop in Bohemia Road, St Leonard’s-on-Sea. Bohemia Road was a good address. Sinclair, now well-known for his own books, was once a provider of second-hand books at a stall in Camden Passage. He also used to produce some fascinating catalogues often featuring Beat-related literature and pulp crime novels. I recall them with pleasure. I can’t claim that my own prowling has ever really been in search of overlooked scarce items. The book scouts that Sinclair writes about were more adept at that. I’ve never been too bothered about books as rare objects. I just wanted to read them, and a grubby hardback, a tattered paperback, a stained old literary magazine, can satisfy me just as much as books in pristine condition or the occasional perhaps-valuable item that I have come across by chance. I remember my delight when, in a now long-since closed shop on the edge of Stockport, I found a couple of American left-wing novels from the 1930s and got them cheap. It wasn’t that they were valuable in money terms. But they were valuable to me for other reasons. And I couldn’t help wondering who had once owned them? It was a time when the old Left was dying off, working-class autodidacts were disappearing, and their terraced houses were being demolished, or sometimes renovated. I could imagine the sons and daughters piling up Dad’s books and selling them to the bookseller. Houses with shelves of old books don’t fit in with gentrification. The bookshops covered in Browse aren’t all of the second-hand variety, by any means, and Ian Sansom’s memoir of working at the original Foyles Bookshop in Charing Cross Road, with the nearby Pillars of Hercules pub, reminded me of the hours I spent in both places. There is still a Foyles, of course, though in a slightly different location, and I don’t want to criticise it, but it seems too shiny and organised for my tastes. I feel happier in the remaining second-hand bookshops further down Charing Cross Road and in Cecil Court. Or in Judd Books and Skoob, both not far from Euston Station. But I’m being too insular and only looking at bookshops in Britain. In Browse, Andrei Kurkov talks about a bookshop in “Chernivtsi in the middle of the Bukovina region in the south-west of Ukraine.” The shop was called Bukinist, its name derived from the French bouquiniste, which inevitably brings to mind the bookstalls along the Seine in Paris. More memories, as it was from one of those stalls that I got a copy of the Olympia Press edition of William Burroughs’ The Naked Lunch. That was in 1962, and the book was still banned in Britain, so I smuggled it home at the bottom of my rucksack. Juan Gabriel Vasquez writes about bookshops in Bogota, and Yiyun Li a bookshop in Beijing. In Cairo, Alaa Al Aswany had a book signing session that overspilled into a discussion about the current political situation in Egypt and the need to protest against a corrupt government. There are articles about bookshops in Nairobi and Bologna. They’re often described as meeting places for students, writers, and others who perhaps just like to browse and buy something they’ve discovered. And talk to each other. I’m reminded of the splendid Compendium Bookshop in Camden Town and often meeting poets and novelists there. I took the American writer Seymour Krim to Compendium when he was trying to find a copy of Evergreen Review which had one of his pieces. And on another occasion I met the late John Platt and we adjoined to a nearby pub where he asked me to contribute to his magazine, Comstock Lode. And Nick Kimberley (later to have his own bookshop, Duck Soup), and after him Mike Hart, behind the counter at Compendium, were always good to talk to. Bookshops are more than just places to buy books. Or they ought to be. Someone once said that at Compendium you could find Mike “at the heart of a group of autodidacts, musicians, writers, lowlifes and drunks.” The shop, described as “the last outpost of bohemianism” in Camden Town, closed as the area became more commercialised. Also long gone is Turret Bookshop, which Bernard Stone over the years operated from various addresses in Kensington, Covent Garden, and elsewhere. Bernard always got out a bottle of wine or vodka , no matter the time of day when I called. And there were readings in his shop which were happy affairs with the drink flowing freely. Bernard was friendly towards little magazines and small press publications and held a good stock of them. Bookshops in Delhi and Denmark, and along with them the stories of the writers who found the way to their doors, and benefited from the experience. Ali Smith frequented the only bookshop in Inverness, Michael Dirda made a journey to the Second Story Books warehouse in Rockville, Maryland, as a snowstorm threatened to develop. The thought of finding something unusual was enough to make him take a chance on being cut-off when it was time to return home. This is a book for all those who love books and the shops that sell them. I’ve been to bookshops in Toronto, New York, Pittsburgh, Amsterdam, Cologne, Berlin, Zurich, Paris, Prague, Seville, Cardiff, Glasgow, Edinburgh, London, and too many others in towns and cities across England to list here. And I hope to continue going to them as long as I’m able to get there. Yes, I know I can easily find books on Abe Books, and I do use their service, but only to get a book I know about and need. And that’s satisfying in its way, but not the same as suddenly stumbling on something I wasn’t aware of, or even if I was I probably would never have bought and read had I not actually held it in my hands. Not too long ago I came across a copy of Leonard Merrick’s While Paris Laughed in a bookshop in Edinburgh and enjoyed it so much that I’ve since tracked down four other Merrick books. But I may never have read Merrick had I not picked up that copy of While Paris Laughed in a bookshop. It’s a collection of stories about an impoverished poet called Tricotrin, and entertainingly plays to the popular notion of the bohemian life. A more realistic and downbeat version of that life can be found in Merrick’s novel, Cynthia, with its struggling writer and his family, unreliable editors and wayward publishers, publications that never prosper, and a permanent lack of money. Some of it was probably based on Merrick’s own experiences in the City of Light. Merrick had been there long before George Whitman arrived in Paris. But Whitman was by nature a bohemian, and once settled in the city he began to work towards his dream of opening a bookshop that would cater for the numerous English-speaking writers and others who were also around. He eventually opened Le Mistral in 1951 and changed its name to Shakespeare and Company in 1964. It was still Le Mistral when I first went to find it in 1962. And there had been a Shakespeare and Company in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s, when Sylvia Beach ran it and Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, and many others of the famed expatriate community frequented the shop. There have been other English-language bookshops in Paris over the years, of course. I recall The English Bookshop from my 1962 visit, and more recently the excellent Village Voice Bookshop in the rue Princesse, though it’s now sadly closed, a victim of the internet and the decline of the area it was in from one with a bohemian touch into a fashionable district of boutiques and trendy bars, The Village Voice was always good for new books from the United States, and for a chat with Michael Neal. The San Francisco Book Company still thrives with second-hand books on the rue Monsieur le Prince. It’s Shakespeare and Company, needless to say, that is the most well-known. It’s lucky with its location, just across the river from Notre Dame, and I suppose the fact of it having survived there for over sixty years now justifies it being described as legendary. George Whitman’s presence on the premises usually added to the atmosphere, and it wasn’t unusual to find a couple of writers also hanging around. I mean a couple of published writers as well as the young, hopeful poets and would-be novelists who were encouraged to doss down in the rooms above the shop in return for a few hours helping out with the chores. Jeremy Mercer’s Books, Baguettes & Bedbugs, published in 2005, is useful for giving an idea of what their experiences were like, though some other publications, usually undated, that emanated from the shop, often had short accounts of their time in the Tumbleweed Hotel by a variety of visitors. I never did stay there myself, but the bookshop was always good for chance encounters. I remember seeing Ted Joans, the black Beat poet there one day, and renewing an acquaintanceship we’d started at the Berlin Literature Festival in 1977. And, on another occasion, coming across two slightly tipsy English poets and adjourning to a nearby bar. They were in Paris for an exhibition they never actually got to, the Kronenbourg proving too strong a counter-attraction, but one of them later commemorated our meeting with a poem in a book called Following the Seine. A history of Shakespeare and Company was sure to be published at some stage, and it’s heartening to find that it has come from the bookshop and not from an outside source. The encouraging thing is that it’s not what might be called a conventional history. The facts are there, but they’re interspersed with numerous photos and other illustrations, memoirs by people who called at or were involved with the bookshop at one time or another, and other odds and ends. The shop had its ups and downs over the years, sometimes because of French bureaucracy, sometimes because of George Whitman’s free-and-easy approach to being the proprietor of a bookshop. He was likely to disappear for lengthy periods and leave the business in the hands of people not suited to running it. The noted writer, Lawrence Durrell, fell out with Whitman because a book-signing at the shop was left to a couple of incompetent young people while Whitman was away, and consequently was a shambles. And there was a disastrous fire in 1990 that might have been caused by the “ancient electrical wiring” or “an errant cigarette from a careless customer”. Or “was it the rejected poet who’d been lurking about?” I’ve encountered some oddballs during my sixty or so years around the poetry scene and its hordes of poets, but the thought of one who might have been an arsonist is disturbing. Not every poet could be trusted, however, and thefts of books were a perennial problem. The poet Gregory Corso, living in the so-called Beat Hotel in Paris, was known to steal books from Shakespeare and Company, just as he did from Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights bookshop in San Francisco. Whitman continued to tolerate him in the shop because he was a good poet. Anecdotes about Whitman and Shakespeare and Company abound. During the 1968 demonstrations Whitman, a one-time communist in the 1930s, sympathised with the students and others who were battling with the police: “Throughout the violence, the bookshop was a refuge. George hosted all-night talk sessions, and he hid those who were trying to escape the CRS.” When the fire broke out he took it in his stride and immediately set to work to put right the damage: “Don’t mourn. Organise,” he’s reputed to have said, quoting the words of the IWW activist, Joe Hill. It might be appropriate, at this point, to mention Whitman’s suspicions about the CIA monitoring both him and the shop because of his radical past and the shop’s open policy about the sort of literature it stocked. He wasn’t just being paranoiac, and it was a fact that the CIA was active in Paris. The writer Peter Matthiessen (author of the Cold War novel, Partisans) later admitted to working on behalf of the CIA during his time in the city in the 1950s. And there is information about The Paris Magazine, edited by Whitman, the first issue of which came out in 1967, the second in 1984 and the third in 1989. Anyone familiar with little magazines, and their inconsistencies, will know that regularity and frequency of publication are not always priorities for them, but three issues in twenty-two years, and with a seventeen-years gap between the first and second, might be something of a record. The magazine has been revived in recent times and looks imposing and has some fashionable names in its contents list, but I still have a liking for those early, idiosyncratic issues that George Whitman published. Shakespeare and Company is a wonderful book, well-produced, and as I mentioned earlier, full of photos and other documents that vividly bring to life the life and times of George Whitman and his bookshop. He died in 2011, though his daughter, Sylvia, had more or less taken over well before that and started “modernising” the shop. It has expanded and now has a café. As she probably correctly predicted, if it wasn’t modernised it was in danger of becoming just a museum piece. I can feel nostalgic for the bookshop that I first experienced in 1962, but I can also understand that change is inevitable.

|