|

BROTHER-SOULS: JOHN CLELLON HOLMES, JACK KEROUAC, AND THE BEAT GENERATION by Ann Charters and Samuel Charters. University Press of Mississipi. 441 pages. $35. ISBN 978-1-60473-579-6 Reviewed by Jim Burns Feb 2011

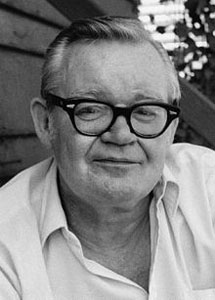

It's doubtful if many of the enthusiasts for Beat writing have paid much attention to John Clellon Holmes. There are numerous books about Kerouac, Burroughs, and Ginsberg, and most of their work is in print. A few anthologies include something by Holmes, and general histories of the Beat movement usually mention him and his novel Go which has fictional portraits of the aforementioned trio and some of the other writers and characters who were around in the late-1940s. But Go is probably the most accurate and honest account we have of that period, and offers a darker picture of the people and events than Kerouac ever came up with. People like their bohemianism to be colourful and entertaining and that may be part of the explanation why Go has never been a widely-read novel whereas On the Road has. There are other reasons, of course, which have to do with the different styles of writing the two novelists used and the publication dates of their books. John Clellon Holmes was born in 1926 in Holyoke, Massachusetts, into a family with roots going back to the early days of colonial America, and links to such people as the Civil War General John Mclellan and the writer Oliver Wendell Holmes. Later, Kerouac sometimes imagined that Holmes had a privileged upbringing, which was far from the truth and caused Holmes to say in response: "Somewhere you seem to have gotten the idea that I'm landed gentry. This is amusing when you consider that very probably your father made more money during his life than mine." And he went on to refute Kerouac's assertion that Holmes was a "man of inherited wealth." In reality, Holmes had a more chaotic and financially unstable young life than Kerouac, though the latter because of his working or lower middle-class background in a small town developed a much less-sophisticated understanding of the world he lived in. Brother-Souls says that, "Kerouac's writing remained consistently personal, parochial, always focused on a small group of friends or a brief relationship with someone in that group, while Holmes in his books continually attempted to draw parallels between his own world and the larger American traditions and literary culture that he considered his own." Holmes never had a extended formal education. He dropped out of school when he was sixteen and picked up routine clerical jobs. But he was conscious of wanting to be a writer and enrolled in an evening class at Columbia University, studying composition and reading James T.Farrell and Ernest Hemingway. In 1944 he was conscripted into the navy and spent a year working as a medical orderly. He never left the USA but did come into contact with many severely wounded men, an experience that had a profound effect on him. He recalled: "Anti-fascist though I had been since 12, the experience ended war for me. Fifty boys my own age died while I watched, helpless to help. A hundred more were crippled forever, and no June night would promise them anything but bitterness. I feel a solidarity with them still." The reference to an early awareness of fascism points to his interest in politics, an interest which developed when he met a fellow-sailor who was a Marxist. Later, when living in New York with his first wife, he read the Daily Worker every day and frequented the Worker's Bookshop. And he began to find his way into the world of would-be writers and intellectuals in Greenwich Village, arguing about politics but finding it increasingly hard to come to terms with post-war developments. The onset of the Cold War, and in particular the Communist seizure of control in Czechoslovakia, were determining factors in his disillusionment with communism. But he never became like Kerouac who, despite some youthful expressions of vaguely left-wing opinions, was always a conservative at bottom and as he got older and drunker raged against "Jews, communists and intellectuals." Holmes had met Alan Harrington, another aspiring novelist, in 1948 and it was through him that he got drawn into Beat circles. He had also started to appear in print, though as a poet, and his work was in such well-regarded magazines as Poetry, Partisan Review, Harper's, and the Saturday Review of Literature. Any young poet would have been happy with being seen in these publications, but his main ambition was to write a novel. He was having problems, though, partly because of his intense approach to writing prose. He believed that a novel "should dramatise ideas" and be part of a "continuing intellectual debate," whereas Kerouac thought of novels as "a free expression of personal experiences" and places to capture "moods." I've got to admit at this point that my personal interests incline me to look on Holmes's involvements and experiences during this period as the most interesting in his career. The account in Brother-Souls brings out some of the frantic atmosphere and the excitement among the shifting crowd of writers, drifters, hangers-on, oddball characters, and others that Holmes encountered. His journals, his novel, and his later reminiscences are full of references to wild parties, marital problems, heavy drinking, and differences of opinion about writing, all of it with the background of bebop, the music that had surfaced in the immediate post-war years and influenced both Holmes and Kerouac. It wasn't all just partying and hangovers, and there was work being done. Kerouac published his first novel, The Town and the City, in 1950 and was working on others. Ginsberg was writing his early poems. Alan Harrington was busy with the book that would later be published as The Revelations of Dr Modesto, and Holmes was beginning to realise, partly thanks to his wife's prompting, that he ought to write about what was directly in front of him rather than trying to create totally fictional characters to carry ideas. It would take a little time, and he would struggle with it, but he did eventually complete the novel that came out as Go in 1952. If Holmes had hoped that Go would bring him success he was soon disappointed. It was reviewed here and there but didn't sell particularly well, nor did its subject-matter arouse a great deal of interest. Holmes was asked to write an article for the New York Times to explain what was meant by the book's talk about a Beat Generation, but the time wasn't ripe for the kind of response that greeted the publication of On the Road in 1957. There was a nervousness in the air in America in the early-1950s, with Senator McCarthy and others like him on the prowl and any sort of deviant behaviour looked on as suspicious and un-American. Interestingly, Brother-Souls suggests that Holmes was too interested in his writing to formulate any strong opinions about what was happening. It does occur to me, though, that bearing in mind his early flirtations with communism, he may have decided that it was best to keep his head down until the anti-communist hysteria subsided. Kerouac had been generally supportive of Holmes's attempts to write a novel based on the activities of their Beat friends, though he wasn't happy about the book's dark vision, nor with the way certain actions were ascribed to the character based on him. There was, too, a degree of hidden resentment about the fact that Holmes seemed to be acting as a kind of chronicler and spokesman for the Beat Generation, though Holmes always acknowledged that Kerouac had coined the term. They were friends but a further rift began to develop when Holmes let it be known that he was working on a jazz novel. Kerouac himself had the same idea, though he never actually completed his book, whereas Holmes was already hard at work on his and an excerpt from it appeared in Discovery in 1953. By this time, however, the New York Beat community, if it can be called that, had broken up as people died, moved away, got involved with other things, and so on. Holmes was locked into a marriage that was falling apart, with his wife rebelling against his moods, his refusal to work at anything other than his writing, his heavy drinking, extra-marital affairs, and the crowd he mixed with. She'd never been impressed with Ginsberg's antics, for example, and her view of Neal Cassady was that he was just a con-man and not "some kind of prophet of the new life." Wives and other women associated with the Beats often had a tough time. Kerouac relied on his mother for financial support, and both of Holmes's wives worked hard at dull jobs while he wrote. There's a revealing passage in which his second wife describes her situation: "He does nothing in terms of shared responsibility for the daily details of human living. His meals are bought, cooked, cleaned up after, his clothes washed and pressed, along with my own, the bills are paid, the phone handled, the cats fed, the house cleaned, his mother placated with time spent with her. I work some of the time and worry all of the time and am worn out the rest of the time."

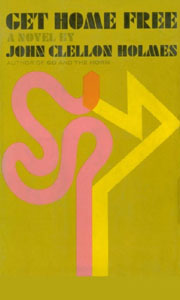

Very few writers make a living from their writing and Holmes was no exception. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s he struggled with his novels, wrote articles for magazines to earn money, and took on part-time teaching jobs. He drank a lot and, at one low point, was arrested for stealing food that he couldn't afford to buy. Two novels were published, The Horn, his jazz book, in 1958, and Get Home Free in 1964, but neither made a great impression either in terms of sales or critical acclaim. Some jazz writers did say that The Horn was one of the better jazz novels. There is, incidentally, a close analysis of the book in Brother-Souls which shows how carefully Holmes constructed it and how it reflected his idea that "the jazz artist was the quintessential American artist - that is, that his work hang-ups, his personal neglect by his country, his continual struggle for money, the debasement of his vision by the mean streets, his ofttimes descent into drugs, liquor, and self-destructiveness," and Holmes related all this to the problems experienced by various 19th Century American writers like Poe, Melville, Hawthorn, Whitman, and others. I think it's obvious that Holmes saw the jazz experience as being not dissimilar to his own struggles to create in a hostile environments It's perhaps interesting to wonder what Kerouac's jazz novel, had it ever appeared, would have been like. The passages that he wrote about jazz, in On the Road and in a few short articles, suggest that he would have followed a looser and less-intellectual line. It was clear to Holmes that, as he got older and literary success evaded him, he would have to find another way of earning a living. As with so many writers before him he turned to teaching and eventually landed a job at the University of Arkansas. He continued to work on his novels, though none of them were published, and started to write poetry again but in a more-open form than the poems which were published in the 1940s. It was in the 1970s that I contacted him and he responded with several poems that appeared in Palantir, a little-magazine I was then editing. I had only a brief correspondence with him but he seemed friendly and relaxed about the fact that I couldn't pay him anything for the poems. It wasn't a problem, he said, and added, "We're all in the same boat, bailing together." His main achievements during these years were the essays he wrote, many of them dealing with personalities of the Beat Generation, such as Kerouac and Ginsberg, and others with people like Gershon Legman, Jay Landesman, and Nelson Algren, who weren't Beats but operated outside the mainstream of American culture. And there were some superb evocations of particular periods, such as the 1940s and 1930s, and of the films of the 1930s. I'm picking out just a few pieces and there were many more, including some engaging travel articles, though Holmes was never a conventional writer in this genre. His approach was much more idiosyncratic and often related more to the people he met than to the places. Always a heavy smoker, Holmes died of cancer of the jaw in 1988. Was he a failure as a writer? I don't think so, and his novels, if not works of the highest order, do have much to recommend them. Go has obvious documentary value and Kenneth Rexroth rightly remarked, "If you want to understand what Allen Ginsberg called 'the best minds of my generation, Go is the book." But it's unfair to rate it solely for its documentary aspect and it has qualities as a novel that are worth taking note of. The Horn was a worthwhile attempt to write a serious jazz novel, one that would go beyond the sensationalism of other books and show how and why the music was created. Get Home Free was flawed but the section called "Old Man Molineaux" can stand on its own and is a marvellous description of a small-town drunk and the area he lives in. There are poems by Holmes that deserve to be remembered, and I've already referred to his essays which, some critics suggest, may be what he will most be remembered for. He once wrote, "my Beat Generation, like the Lost Generation before it, was primarily a literary group, and not a social movement; and probably all that will last out of our Beat years are a rash of vaporous anecdotes, and the few solid works that were produced." If that's the case then something that Holmes wrote is sure to be among those works. I've concentrated on Holmes in this review, but Brother-Souls closely ties in his activities with those of Kerouac. It seemed to me to be right to do this because Kerouac's life and books have been written about in more than one biography and academic study, whereas Holmes has been neglected for the most part. Ann Charters and Samuel Charters deserve credit for drawing attention to Holmes and their way of doing it makes complete sense. Anyone unfamiliar with Holmes will be able to see how he was an important member of the Beat movement and how his friendship with Kerouac affected both men. It was, admittedly, a friendship that had its problems, many of them resulting from Kerouac's paranoias and resentments, not to mention his alcoholism, but it finally survived over the years until Kerouac's death. If anyone wants to know how much Holmes cared for Kerouac they should read his "The Great Rememberer" or "Gone in October," two moving essays in which he celebrated his friend.

|