|

BOHEMIAN LONDON

: FROM PRE-RAPHAELITES TO PUNK

By Nick Rennison

Oldcastle Books. 224 pages. £12.99. ISBN 978-1-904048-30-5

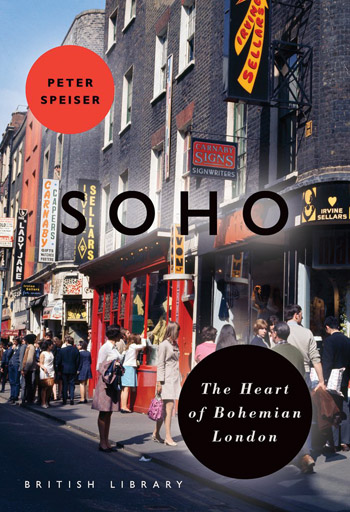

SOHO : THE HEART OF BOHEMIAN LONDON

By Peter Speiser

The British Library. 192 pages. £10.00. ISBN 978-0-7123-5657-2

Reviewed by Jim Burns

Bohemia?

What is it, where is it, does it exist anymore? There are

suggestions that it doesn’t in any meaningful way, in which case my

questions should be, what was it, where was it? More than one

commentator on the subject has suggested that bohemia is always

yesterday, and memoirs by those who lived in bohemia at one time or

another often give the impression that what they experienced was the

genuine thing and anything coming after just a pale imitation of it.

Henry Murger, the man usually held responsible for starting the

bohemian ball rolling in the 1840s, was of the opinion that bohemia

couldn’t exist outside Paris, and that it had

passed when his particular group broke up.

Nick Rennison outlines the birth of bohemia in his

briskly written survey of where it was to be found in London. Like most accounts, he starts in Paris

with Henry Murger’s Scènes de

la vie de Bohème (Scenes

of Bohemian Life) which was published in book form in 1851,

though the first of the

sketches which make up the so-called novel had appeared in a Paris

publication, Le Corsaire,

in 1845, and a play by Murger and Théodore Barrière, had been based

on them in 1849.

It might be worth noting that Balzac’s

A Great Man in Embryo, published in 1839 as part of

Illusions perdues (Lost Illusions), provided a vivid plcture of the Parisian literary

world of struggling poets and journalists that Murger would have

known. Murger’s version of it tended to play up the humorous side on

the whole (the death of Mimi and some other details indicate that

there were dark aspects to bohemia), and when Puccini came along

forty or so years later, and presented his opera, La Bohème, to the

world, romanticism really took over. The harsh realities of bohemian

life were made to seem tolerable because of the compensations of

wine, women, and song.

Murger, Puccini, and George Du Maurier with

Trilby, popularised

bohemia, but there was nothing new about it even when Murger

arrived. There had always been hordes of minor writers attempting to

hack out a living in London, Paris, and no doubt elsewhere, with

poems, plays, satires, scurrilous suggestions, and anything else

that might earn them a penny or two to pay the rent and purchase the

food and drink (especially the latter) they needed. Grub Street in London was, for a time, a centre for them, and

even when they moved on the name stuck. The link between Grub Street

and bohemia was always easy to see. There may be some truth in

Malcolm Cowley’s statement that “bohemia is Grub Street on parade”.

It’s usual to acknowledge that the term bohemian

came into use around the 1830s in Paris, the oddly-attired students

and scribblers in the Latin Quarter reminding people of gypsies who

were, at that time, thought to have arrived from the actual

land

of Bohemia. But

there is an interesting book, discovered by the American historian,

Robert Darnton, which was published in 1790 with the title, Les

Bohémians (The Bohemians), and which is about a group of feckless philosophers

of one kind or another who function almost as strolling players,

discoursing on philosophical questions, swindling country folk,

stealing what they need to in order to survive, seducing any woman

in sight, and generally misbehaving. According to Darnton, the book

was written by Anne Gédéon Lafitte, Marquis de Pelleport while he

was in the Bastille. In a nearby cell was the Marquis de Sade, busy

churning out pornography.

Pelleport was a man, despite “Anne” being part of

his name. His activities, as told by Darnton, certainly display an

affinity for Grub Street bohemianism. A translation of

The Bohemians was

published by the

University

of Pennsylvania

in 2010. In his long, informative introduction Darnton mentions that

he came across a reference to “bohemians”, in the sense of

disreputable types, in a book published in

London

in French in 1783. There were quite a few exiled French hack writers

living in London at the time, many

of them banished from their own country because of libellous and

salacious material they had written.

I think the main point to be made is that the Grub

Street hacks were living the way that they did out of necessity,

whereas many bohemians, once the idea became widely publicised,

chose to live in garrets and suffer for their art. Or pretend to.

The rise of the Romantic in literature had encouraged poets

to see themselves as at odds with the world. They would not churn

out doggerel for pay, and if the public didn’t care for what they

did produce, well that was the public’s fault.

I’ve never been sure that bohemia ever established

itself in

London in the style that it did in Paris. Café life didn’t

exist in the same way in the British city, and despite the

attractions of pubs they were never really likely to appeal to poets

and artists as places to engage in spirited discussions about art

and literature and philosophy.

Joanna Richardson in The Bohemians: La vie de Bohème in Paris,

1830-1914 (Macmillan, London, 1969) reckoned that the

“matter-of-factness of the Englishman”, and his reluctance to

“prolong intellectual conversation”, worked against the kind of café

life that encouraged bohemianism in Paris.

Rennison provides a brief look at Grub Street, an

actual location as well as a descriptive term. Alexander Pope

satirised the hacks in The

Dunciad, and books have been written about them. One of the more

recent, Vic Gatrell’s The First Bohemians (Allen Lane, 2013), shows how Covent Garden took

over from Grub Street as a centre for the crowds of impoverished

writers and artists desperately trying to earn a living at their

respective trades, and in the process often resorting to trickery,

pornography, and worse to get by.

As the subtitle of

London Bohemia suggests,

Rennison’s story really gets off the ground with the

Pre-Raphaelites, whose paintings can still sometimes cause a fuss,

if the removal of a work by J.W. Waterhouse from public display in

Manchester City Art Gallery is anything to go by. (It was later put

back after protests about censorship).

19th century artists, not all of them

Pre-Raphaelites, often had a predilection for naked women and girls,

some of them below the age we’d now consider acceptable for models.

The artists’ patrons no doubt favoured them, too.

Rennison mostly focuses on Dante Gabriel Rossetti,

whose activities with various women, not to mention his liking for

alcohol and drugs, makes for a lively tale. As usual with accounts

of bohemia, not much is said about the work that Rossetti produced

as a painter and poet. We are told about him burying a collection of

poems with the body of his wife, and later having her body exhumed

so he could recover the manuscript for publication. That’s the thing

with bohemia, it’s the antics of bohemians that take precedence over

the work. It’s true that a lot of bohemians were “failures” (but

then, “give flowers to the rebels failed”), and their works

ephemeral, but there is an attraction about forgotten books and

magazines that I find hard to resist. A reference or two to

Pre-Raphaelite poets, and their short-lived (four issues) little

magazine, The Germ, might

have been useful. It may well have been one of the first little

magazines that marked the march of bohemia, and became its mode of

expression. Little magazines and small press publications record the

history of bohemia.

Rennison does devote some attention to a couple of

little magazines that were related to the bohemianism of the 1890s.

The Yellow Book and

The Savoy have come to represent the era in some ways, though in the

case of The Yellow Book

its reputation for decadence largely resulted from the fact that

when Oscar Wilde was arrested he was carrying a yellow-backed novel

and the newspapers said that it was a copy of

The Yellow Book. They

probably weren’t bothered about the inaccuracy,

The Yellow Book in their minds being associated with foreign

influences, especially from

France, and so at odds with British

tastes for sport, plain speaking, and down-to-earth general

behaviour. The fact that London was packed with prostitutes, both

male and female, that children could quite easily be bought to

satisfy the desires of men with money, including members of the

aristocracy, and that extreme pornography was obtainable from “under

the counter” sources, appeared to pale into insignificance compared

to Wilde’s peccadillos. Or so the establishment obviously thought.

Both publications published a range of writers and

artists, but The Yellow Book

was, on the whole quite decorous, though Aubrey Beardsley’s drawings

may have hinted at suspect ideas. They were quickly dropped from its

cover and contents when Wilde fell foul of the law. Leonard

Smithers, the editor of The Savoy, was, to be fair, a somewhat dubious character. He peddled

pornography on the side, while at the same time publishing poets

like Ernest Dowson and Arthur Symons, both of them symptomatic of

1890s decadence, though in Symons case his verses about assignations

with actresses (“The pink and black of silk and lace,/Flushed in the

rosy-golden glow/Of lamplight on her lifted face;/Powder and wig,

and pink and lace”.) are generally thought to be inferior imitations

of the kind of writing by French poets who he admired.

Smithers himself came to what might be seen as a

suitably bohemian end, sinking into poverty and addiction, and

finally dying naked in an unfurnished house, his body surrounded by

empty bottles of Dr Collis Browne’s Chlorodyne, a patent medicine

containing laudanum, tincture of cannabis, and chloroform. There are

several versions about the circumstances involving Smithers’ death,

and they’re fully outlined in James G. Nelson’s

Publisher to the Decadents

: Leonard Smithers in the

careers of Beardsley, Wilde, Dowson (Pennsylvania State

University Press, 2000).

Other 1890s personalities met similarly tragic

ends. Ernest Dowson died from consumption, exacerbated by his heavy

drinking. Lionel Johnson, another heavy drinker died from a stroke.

John Davidson committed suicide.

The fine short-story writer Hubert Crackanthorpe died in a

mysterious manner in Paris. Aubrey Beardsley died of tuberculosis.

The little-known John Barlas went insane. Arthur Symons, suffering

from the effects of syphilis, spent time in an asylum. Francis

Thompson fell into “opium and squalor”. Vincent O’Sullivan did

survive until his seventies, but died in poverty in

Paris. It’s easy to mock the fragile careers

of these people, but I have a fondness for their poetry and prose.

Perhaps it’s relevant to mention at this point one

of my own favourite novels, George Gissing’s

New Grub Street. It isn’t

about bohemianism in the way that the 1890s poets may have lived and

died, but it seems to me to exemplify how Grub Street and bohemia

intermingled. Some of Gissing’s characters toil in the “valley of

the shadow of books”, the British Museum Reading Room, where they

write erudite articles for intellectual magazines. There are also a

couple of novelists, one a kind of proletarian trying to produce a

social-realist book that will probably never be published, the other

aiming for something different but whose books don’t sell. And

there’s a man who will succeed because he’s learned how to write for

the popular publications that are springing up to cater for a

newly-educated public that doesn’t want intellectual fare but likes

to see itself as intelligent and informed. He’ll live well, but the

others will struggle to make ends meet, just like the bohemians.

It has been suggested that the Wilde trials and

their attendant publicity had a negative effect on the development

of literature in Britain, with

many poets and novelists being reluctant to push too far in

expanding the boundaries of style and expression. It might also have

put a damper on flamboyant displays of bohemianism, long hair and

colourful clothing being associated in the narrow British mind with

homosexuality. It’s a

theme investigated in Hugh Kenner’s

A Sinking Island (Knopf,

1988).

There were examples of bohemian behaviour in the

lIves of artists like Augustus John and Jacob Epstein. John cut a

swathe through London society, and

especially the female part of it, with his good looks and obvious

talents as a painter. Epstein also attracted attention, sometimes

because the public sculptures he was commissioned to construct upset

the puritans. Both John and Epstein frequented the Café Royal, the

haunt of many writers and artists over the years.

Did Wyndham Lewis go there? He founded one of the

few genuine British art movements, Vorticism, and published a couple

of issues of Blast, a

publication that has a place in the history of avant-garde little

magazines. Lewis was

also a novelist and an excellent painter. An exhibition at the

Imperial War Museum North in Salford

in 2017 fully covered the range of his activities. He was a great

arguer and not looked on too kindly by the liberal establishment in England because of his expressed

admiration for Fascism in its early phases. He later seems to have

changed his mind.

I have to admit that Rennison’s suspicions about

whether or not the Bloomsbury group

were bohemians appealed to me. As he puts it: “By some definitions

of the word, it is difficult to categorise the

Bloomsbury artists and intellectuals as ‘bohemian’. If

they were, they were upper middle-class bohemians who often found it

difficult to forget that they were upper middle-class. They were

bohemians who needed to employ maids and cooks to cater to their

everyday needs”. The fact that they liked to bed-hop didn’t make

them into bohemians.

The Great War had an effect on bohemia, with people

either volunteering or eventually being conscripted for military

service. And no one was likely to be interested in bohemian capers

while thousands of men were dying in

France

and elsewhere. There was certainly nothing like the democratic

spirit that was prevalent during the Second World War and which,

from a literary point of view, led to an outburst of activity at all

levels of society and the birth of numerous little magazines and,

despite paper rationing, many small presses. It’s impossible to

imagine publications like Penguin New Writing and Reginald Moore’s

Modern Reading being around between 1914 and 1918.

When Rennison gets into the 1920s I have to admit

that my interest began to wane a little. I’ve always felt that

bohemia has little meaning if it’s not linked to the arts. His

account of the period tends to focus on various clubs that were

meeting places for bright young things who may have sniffed cocaine,

slept around, and provided material for novelists who observed them,

but they were, on the whole, non-productive as writers and artists

themselves A few may have written memoirs in later years, but I

can’t pretend to be concerned about their lives.

Luckily, the narrative picks up when he moves on to

the 1930s. Pubs became more important than clubs. Fitzrovia, the

area to the north of Oxford Street bounded on one side by Tottenham

Court Road, became popular, and there were bookshops and magazines,

political demonstrations, the Surrealist Exhibition in 1936, and

left-wing political groups which encouraged poets and others to lend

their voices to the demands to alleviate the suffering caused by the

Depression and the threats caused by the rise of Fascism. The

Spanish Civil War focused many minds on the need to take a

more-serious stance in terms of both personal behaviour and

commitment to something other than personal achievement. Was this

likely to lead to bohemian lives? Well, it could do if one considers

how money was short and opportunities to get ahead limited. A

commitment to a political cause, coupled with a commitment to

writing poetry or a novel, might incline a writer to eke out a

frugal, bohemian-like existence so as not to compromise. But not

everyone was politically inclined.

Parts of Ethel Mannin’s novel,

Ragged Banners (Jarrolds, 1931) are set in this world. In one scene

in “Reinhardt’s (in reality The Fitzroy Tavern, often called

“Kleinfeld’s” after its landlord) there are references to “a frowsy

woman in a disreputable old pony-skin coat…….with her glazed eyes

and tawdry clothes, a ruin of a woman”. Someone explains that she

was once famous in Montparnasse.

It’s a description of a character clearly based Nina Hamnett, who

naturally took offence at being portrayed in this way and threatened

to give Mannin a black eye if she saw her again. Denise Hooker’s

Nina Hamnett: Queen of Bohemia (Constable, 1986) is an excellent

biography of the artist.

During and after the Second World War some of the

action shifted to Soho, and I’ve

got to acknowledge that I have an interest in the literature and art

of the 1940s and early-1950s. In recent years, I’ve travelled to

Edinburgh to see an exhibition of the work of the Two

Roberts (Colquhoun and MacBryde) and to

Chichester for another about John Minton, as well as to

other towns and cities where relevant work could be seen. And I’ve

been lucky enough to have met W.S.Graham, David Gascoyne, John

Heath-Stubbs, and some more survivors from those days.

I’ve also collected the books and little magazines

that published the poets and prose writers, not paying excessive

amounts for them but instead prowling around second-hand bookshops,

charity shops, and market bookstalls. All that was in the days

before the internet and when there were still plenty of second-hand

bookshops. It never bothered me that the books were grubby and the

magazines occasionally tattered. If all the pages were there, I was

happy. It also pleased me that I once participated in a poetry

reading in an upstairs room at the “French”, the name given to the

York Minster in Dean Street, and on another occasion watched the

landlord eject an inebriated Jeffrey Bernard from the premises. All

that was some time after the glory days of the Forties and Fifties,

but the shadows of old bohemians hovered in the corners of the room.

But I’m digressing and Rennison’s colourful account

encompasses Francis Bacon, John Deakin, Lucien Freud, and others who

now have books and articles written about them. The thing is that,

for all their waywardness in the French or the Colony Room, Bacon,

Freud, Minton, Colquhoun, MacBryde, and many others, did also

produce some work of value. So did writers like Julian

Maclaren-Ross, George Barker, David Wright, Paul Potts,

Philip O’Connor (his Steiner’s Tour, published by the Olympia Press in Paris in 1960 is

probably forgotten now, but I enjoyed it), and even Jeffrey Bernard,

whose Spectator columns were always a pleasure to read.

Does anyone remember John Gawsworth? He met a

bohemian end, alcoholic and overlooked, though in his day he had

been a productive poet and an active editor and anthologist. His

poetry was what is usually referred to as traditional. The Spanish

writer, Javier Marías wrote about him in his novels

All Souls and

Dark Back of Time. And how about the bookseller David Archer, who

spent all his money on publishing poets and, cast aside in the

pop-dominated 1960s, committed suicide in a hostel for the homeless?

A friend of mine, now dead, worked in Archer’s bookshop for a brief

period in the late-1950s and liked the man, but thought him

unworldly when it came to business matters.

There are novels from the late-1940s and 1950s that

are worth reading for their pictures of the period, among them

Roland Camberton’s Scamp

and Colin Wilson’s Adrift in

Soho. It may be relevant to mention that, years ago,

I did a poetry reading with an older poet who had been in

London

around 1950. One of the poems I read imagined walking through

Soho

and thinking that the ghosts of old bohemians were lurking in

doorways and around the next turning. He had actually encountered

some of the Soho literary bohemians and, in his view, they were better

read about than experienced. He didn’t have a high opinion of them

or their poems.

Rennison points out: “The supporting cast of

characters in Scamp and

Adrift in Soho are painters, philosophers, and traditional bohemian

eccentrics”, with the central characters out to achieve some sort of

literary status. But by the late-1950s, music was beginning to

dominate. The new literature saw “a future in which literature and

the visual arts will lose their primacy and music will take centre

stage”. I suppose as

someone who was always a great jazz fan and collector (my first

visit to a London jazz club was when, at the age of sixteen in 1952,

I went to the Studio ’51 in Great Newport Street, just off Charing

Cross Road, to hear some of the early British bebop musicians) I

might have been expected to have taken a tolerant view of music

coming to prominence. But I hadn’t foreseen the dominance of pop

music, and it eventually struck me that it had a negative effect on

bohemia. It’s difficult to think and talk when loud music is playing

endlessly.

Music seemed to bring the ethics of the market with

it and that inevitably meant publicity and a hunt for success. Big

money was often involved and businessmen stepped in to take over. Bohemia had always been a small-scale thing,

centred on a few cafés, pubs, and bookshops. The magazines and

small-press publications that were hallmarks of bohemia were never

expected to sell in large numbers. There were, of course, writers

who spent some time in bohemia and moved on to become best-sellers.

There were artists such as Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud who

achieved fame. But they often didn’t seem to change in their basic

attitudes, and it all seemed different from the world of pop

culture. There’s an interesting passage in Edward Field’s memoir,

The Man who would Marry Susan

Sontag (University of Wisconsin Press, 2005): “It was Andy

Warhol who declared the end of bohemianism with his camp emphasis on

celebrity. Suddenly becoming successful and famous became the goal

of creative artists and the bohemian ideal was finished”.

The onslaught of pop culture didn’t wipe out

literary activity, and in some ways it may have helped it by

providing outlets for magazines and pamphlets and books from small

presses. I spent a lot of time in the Sixties and Seventies visiting

Zwemmer’s on Charing Cross Road, Indica on Southampton Row, Mandarin

Books in Notting Hill, Bernard Stone’s bookshops in their shifting

locations; Kensington Church Walk, Covent Garden, and one I can’t

place, though I recall reading there. There was also the splendid

Compendium Bookshop, described as “a bohemian outpost in Camden Town”.

It was something of a boom time for little

magazines (I started one myself which struggled through eight

issues) and poetry readings in all sorts of pubs, clubs, private

homes, bookshops, and other places, so it

wasn’t all the sound of music. And “alternative” bookshops which

were always happy to stock poetry magazines and pamphlets opened up

in many towns and cities. A lot of them, like the publications they

sold, were short lived, but that was often the way in bohemia.

I have to admit that, sitting in the audience at

the big 1965 Albert Hall reading by Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Allen

Ginsberg, and Gregory Corso, I had a feeling that it was an event

rather than a great reading, and that it was too big to be genuinely

bohemian. I had met Alexander Trocchi in a pub a year or two before

he compered the Albert Hall show, and it seemed more natural to come

across him in that setting with poets and little magazine editors

exchanging information and gossip.

Rennison in his epilogue reflects on bohemia today

and mentions the Groucho Club. It always struck me that a club like

it was the very opposite of what bohemia stood for. There was, of

course, the Colony Room, famous for its bohemian clientele, but it

was an exception to the rule. Informal meetings in pubs and cafés

were better suited to bohemia. I may be prejudiced and I’ve always

preferred pubs to clubs, though I can recall being taken to Soho

drinking clubs by Albert McCarthy, editor of

Jazz Monthly, in the 1960s when pubs closed at 3pm. Albert had been

around Soho since the 1940s and

knew many of the writers and painters of those days. He had known

Wrey Gardiner, who edited

Poetry Quarterly and ran Grey Walls Press. Gardiner’s own books,

The Flowering Moment and

The Dark Thorn, probably

wouldn’t suit contemporary tastes – they’re too effusive and

emotional – but are worth hunting for. When he died in 1980 Derek

Stanford wrote a poem in which he imagined Gardiner “behind a coffee

stall with some young Mimi,/sharing with her a new anthology/without

a penny and without a care.” Definitely a bohemian.

Rennison isn’t complimentary about those who

frequent The Groucho Club: “Certainly many members of the Groucho

wanted the wider public to believe that it was upholding bohemian

traditions. There was a kind of self-consciousness in their

behaviour. Paradoxically, this had the effect of making them seem

less free and unconventional than their predecessors. Old-style

bohemians behaved as they did because it came naturally to them.

Groucho bohemians always seemed to have one eye on the photographers

and the gossip columnists”. The influence of pop/celebrity culture

again.

Peter Speiser’s

Soho: The Heart of Bohemian

London doesn’t just focus on the bohemians, and is more of a

general history of the area. It does have brief comments on many of

the same people that Rennison deals with (Nina Hamnett, for example,

and her sad story of bohemian decline. A fictional character in

Julius Horwitz’s wartime Soho novel,

Can I Get There by

Candlelight, published by Deutsch in 1964, is based on her), but its main value, in the context I’m writing

about, may be as a kind of companion volume to Rennison’s

entertaining history of London bohemianism. The bohemians were only

one relatively small part of Soho. It’s perhaps a tribute to the other residents (and

they often were residents, whereas quite a few of the bohemians

weren’t) that their antics were tolerated. Was that because many of

the residents weren’t English?

Speiser documents the histories of different groups

of immigrants who have clustered in Soho

over the years. As he says: “Soho’s history is inextricably linked

with that of London’s immigration”.

They opened shops and restaurants and brought variety to what was

often a bland British range of foods on offer. They also often

brought their politics with them. Karl Marx and his family lived in

Soho

for a time. (See Rosemary Ashton’s

Little Germany: German

Refugees in Victorian Britain, Oxford University Press, 1986).

He also provides information about the theatres and

other places of entertainment, and the performers who appeared in

them. One of the theatres mentioned is The Alhambra, which “hosted

the first ever performance in

London of the French can-can – which promptly

cost the Alhambra

its dancing licence”, (more English puritanism?). In a

recently-published book,

Arthur Symons: Spiritual Adventures (The Modern Humanities

Research Association, 2017) there is a reprint of an essay about the

Alhambra

by Symons which originally appeared in

The Savoy in September,

1896. Symons clearly enjoyed going there, though he was more

concerned to write about ballet rather than the can-can.

Both books have useful biographies, though any

listing of books about bohemia can always be added to. Before

closing this review I’d like to mention another book that came to my

attention and has links to Grub Street, if not bohemia.

The Rivals of Sherlock Holmes,

edited by Nick Rennison (No Exit Press, 2008) reprints detective

stories from the days when The

Strand and similar publications

carried short stories, alongside other material. It was a

relatively good time for writers who could turn out entertaining

stories on a regular basis, though I don’t doubt that some of them

weren’t exactly living in luxury. Most writers don’t. Grub Street is

always with us. Bohemia

might be a thing of the past. And then again, it might not.

|