|

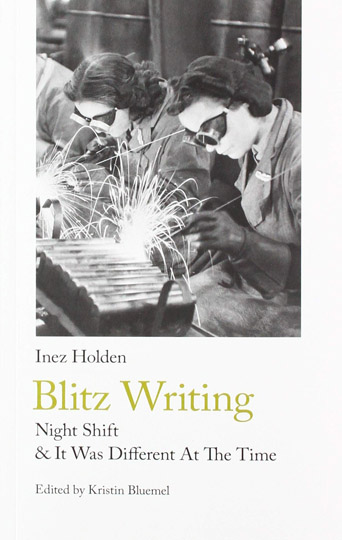

BLITZ

WRITING : NIGHT SHIFT & IT WAS DIFFERENT AT THE TIME

By Inez Holden

Handheld Press. 194 pages. £12.99. ISBN 078-1-912766-06-2

Reviewed by Jim Burns

What did I know about Inez Holden before receiving this welcome

re-issue of two of her short novels from the 1940s? Only a little, I

have to admit. I had read an amusing story, “Uncle Drunkle”, in an

old copy of Writing Today,

edited by Denys Val Baker and Peter Ratazzi in 1943. And there was

another, “The Flat Above Me”, in

Penguin New Writing 9

(1941), edited by John Lehman. These were publications I’d picked up

in second-hand bookshops as I hunted for grubby copies of magazines

from the 1940s.

Andrew Sinclair mentioned Holden a couple of times in

War Like A Wasp; The Lost

Decade of the Forties (Hamish Hamilton, London, 1989) but didn’t

include any of her work in

The War Decade: An Anthology of the 1940s (Hamish Hamilton,

London, 1989). Holden’s “According to the Directive” was selected

for Wave Me Goodbye: Stories

of the Second World War, edited by Anne Boston (Virago, London,

1988). I picked up bits of information from the notes on

contributors in these publication, but it was Celia Goodman’s “Inez

Holden: A Memoir” in London

Magazine (December/January, 1993/94), edited by Alan Ross, that

helped me to get a better grip on her personality and writing

career.

Holden was born in 1903 or 1904 (her parents didn’t bother to

register her birth) into a financially comfortable but somewhat

eccentric household. Her mother was a noted “Edwardian beauty who

had owned fifteen hunters and was known as the second best

horsewoman in

There was more to her than the frippery of the bright young things

of the time. She had a talent for writing, and in the late-1920s and

early-1930s she published three novels which recorded “the

frivolous, absurd lives of the privileged characters who could have

stepped out of the pages of Evelyn Waugh’s

Vile Bodies”.

It’s difficult to determine exactly when and how Holden became more

socially and politically conscious, both in her life and writing.

Like other writers, she probably reacted to the tensions of the

1930s as the Depression brought poverty to millions of people and

fascism began its inexorable rise in

When the war started in 1939 Holden, like many other people, either

volunteered for, or was conscripted into, the work force required to

replace the men from factories and other locations who were being

called-up for the armed forces. She did some basic training as a Red

Cross nurse and worked as an auxiliary in hospitals and first-aid

posts during the blitz, and later spent time in an engineering works

as a machinist producing parts for aircraft. Her experiences

provided the basic material for

Night Shift and

It Was Different at the Time.

It Was Different at the Time

was written in the form of a diary, though not with a strict series

of daily entries. It moves through a period from April, 1938 to

August, 1941, focusing on certain months in each year, and building

up the approach to war, its start, and the onset of bombing raids on

She has a friend, Victor, who has just returned from

When war was declared, Holden took on work as a Red Cross Nurse, and

her experiences began to widen. The descriptions of the hospital

wards are brisk and to the point, and her quickly-established

portraits of staff and patients soon create a wide picture that the

reader can clearly see. People have personalities and are not just a

faceless mass. Much of the work that Holden did was routine and

designed to support the qualified nurses, but she seems to have been

present during at least one operation. Taking down details from a

patient she finds that he has no next-of-kin, no friends, but she is

impressed by his “apparent happiness. He was uninhibited, without

fear, smiling and strong”.

Later, working at a first-aid post, she watches the “demolition men,

rescue parties, and stretcher bearers” being called out night after

night. Like the firemen, they work while the bombs are still falling

and the fires raging, and don’t always return. Harry, a popular

officer – “Always there when anything’s on…..Right on the spot at

the start and, and the last to leave at the finish”, in the words of

a member of his team – goes out one night and is killed.

Night Shift

picks up Holden’s story after she left working as a Red Cross nurse,

and obtained employment as a machinist in a factory. It covers a

working week, Monday through to Saturday, with the actual work being

repetitious and seemingly needing only basic instruction before the

operative is left to get on with the job. The employees were mostly

women, though the foremen and supervisors were all men. Pay and

conditions were not good, and the long hours (up to

There is a woman called Feather among the workers and she is clearly

very much like Holden in being better-educated, if not in a formal

way, and wider-travelled than her colleagues. She probably

represented Holden, though the anonymous narrator talks about her as

just being one among many. But, as in

It Was Different at the Time,

the workers aren’t a nameless mass. Many of them are named and

given certain distinctions of character that enable the reader to

see them as individuals. They talk about their husbands and

boyfriends, many of who are already in the armed forces, and about

what they do when they’re not at work.

The hazards of factory work, especially at night, while the Blitz is

at its height are outlined. Everyone is conscious of the fact that a

bomb may hit the factory at any time. When one does while the

Saturday night shift is working, the narrator is lucky in that she

had been transferred to a Sunday night shift, and so is not killed

or injured. Her situation brings out how much it was a matter of

chance who lived or died. Another woman is doubly lucky. She missed

the Saturday night shift because her house was damaged by a bomb

blast and she survived but couldn’t get to work. Death is all

around, and people just get on with what they have to do.

In many ways, Holden’s writing is much more convincing than later

fictional recreations of the Blitz. Written while the events she

describes were taking place, it still has a fresh feeling that gives

it an immediacy. She keeps her prose simple and describes what she

has seen without fuss:

“I went up to the top of one of the empty houses and looked out over

It often strikes me that wartime circumstances led many writers to a

direct and straightforward way of writing. There wasn’t a mood or an

inclination to experiment, in either prose or poetry. Communication

was the key factor when writing a story or a poem, and the aim was

to reach as wide an audience as possible. No-one, writers and

readers, wanted to waste time. Short stories, short novels, short

poems predominated. Little magazines with compendiums of stories and

other material that might be read in the barrack-room, the factory

canteen, or while waiting to be called out to a fire, were popular

and sold in numbers that would astound editors of literary

publication today.

What happened to Inez Holden after 1945? Despite being widely

published in a variety of magazines, and with seven novels (two

published in the early-1950s) and two short-story collections to her

credit, plus writing film-scripts for J. Arthur Rank, she was never

a best-selling author. Kristin Bluemel sums up her situation in

these words: “During her lifetime, Holden achieved publication but

not fame, her novels and short stories and journalistic work failing

to attain the popularity or influence achieved by many of her writer

friends”. She doesn’t appear to have ever earned a lot of money from

her writing, and presumably may have had an income from her family

background. According to her cousin, Celia Goodman, Holden wrote

only short stories, many of them published in

Punch, after her last

novel appeared in 1956. She died in 1976.

I think it’s worth quoting Kristin Bluemel again when she sums up

what Holden achieved with the two works I’ve reviewed; “Despite a

career that produced no best-sellers and earned no literary awards,

she composed a life out of the colourful scraps of material that

others left behind and wove from them stories of the everyday art of

survival in a city that was falling down and in a country defying

destruction”

A couple of final notes that may be of interest. A character called

Felicity crops up in It Was

Different at the Time, and was based on her friend, Stevie

Smith. In return, Smith based someone called Lopez in her novel,

The Holiday, and her

short story, “The Story of a Story”, on Holden. And, though it

wasn’t quite like Marcel Proust’s experience, memories of my

childhood during the war came flooding back when I read Inez

Holden’s reference to a meal of corned beef and fried potatoes in

Night Shift. I thought it

was a great treat at the time.

|