|

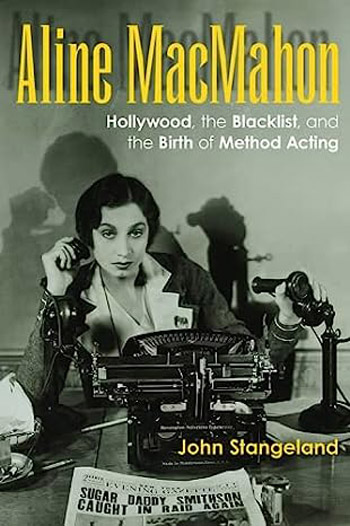

ALINE MacMAHON : HOLLYWOOD, THE BLACKLIST, AND THE BIRTH OF METHOD

ACTING

By John Stangeland

University Press of Kentucky. 340 pages. $40. ISBN 978-0-8131-9606-0

Reviewed by Jim Burns

There are actors whose names may not mean a great deal unless one is

a particularly dedicated follower of Hollywood history. But when

seen on screen they are instantly recognisable. Aline MacMahon is

one such example of someone with a distinctive face who never

achieved star status. Her career saw her mostly restricted to

supporting roles, despite her acting ability often being far

superior to that of her co-stars. But Hollywood didn’t consider her

beautiful, and she unfortunately only started in films when she had

turned thirty, and that alone may have been a key factor in her

largely being limited to parts as a character actor.

She was born in 1899 in McKeesport, Pennsylvania. Her father was

from an Irish-American-Jewish background, and her mother was

Russian-Jewish. The family moved to Brooklyn in 1902. Aline’s

mother, a frustrated actress, seems to have been determined to groom

her daughter for the stage, and arranged for her to have elocution

lessons and to take part in public speaking shows where Aline

recited poetry and other material. Her father had connections to the

arts as a writer and editor at

the popular magazine,

Munsey’s Weekly. There was also an aunt, Sophie Loeb, who was

active in social reform and opened Aline’s eyes to the plight of the

less fortunate in society by taking her on visits to the slums.

Aline enrolled at Barnard College in 1916 and took part in student

drama productions where she attracted enough attention to be offered

a job with the Provincetown Company. She turned it down and instead

visited Europe. When she returned she was involved with the American

Laboratory Theatre, which had links to the Moscow Arts Theatre and

the ideas of Stanislavski. It was her first encounter with what

became known as the “Method” school of acting. The leading light of

the American Laboratory Theatre was Richard Boleslavsky, a devotee

of Stanislavski’s approach to acting with its realism and

encouragement to the actors to identify with the characters they

were portraying. Aline thought she was lucky to have been taught by

Boleslavsky and considered herself something of a pioneer in

bringing elements of Method acting to the American stage.

She generally received excellent reviews for her stage work, though

she expressed some discontent with the fact that a contract she

signed with the Shubert Theatrical Agency meant that she had to take

on roles that she felt didn’t give her the opportunity to exercise

her full potential as an actress. It was a situation that she was to

experience again when she moved to Hollywood and had a contract with

the Warner Brothers studio. However, while working in the theatre,

she did achieve some successes. One of them was in the Eugene

O’Neill play, Beyond the

Horizon, and John Stangeland says that she “became the

uncontested dramatic sensation of the New York theatre world”. One

critic remarked, “She it was who largely made the production a

delight to see”. And Alexander Woolcott wrote that she “played a

bitter, tragic role with extraordinary beauty, vitality and truth”.

The New Yorker enthused

about her, and Noel Coward said, “The performance of a comparatively

young actress Aline MacMahon, remained in my mind as something

astonishing, moving and beautiful”.

I’ve moved quickly through Aline’s experiences in New York and

Stangeland provides a much more detailed account that gives a

fascinating picture of the ups and downs of working in the theatre

and the effects felt by actors and others as the 1929 stock market

crash began to savage the economy and cause mass unemployment and

bank closures. Nonetheless Aline and her husband, the architect

Clarence Stein, decided they were financially secure enough to make

a trip to India. Stangeland thinks that the couple were “gingerly

exploring socialist ideas, class and income inequality foremost

among them”. And that they were curious about Mahatma Gandhi’s

“non-violent struggle against the British Empire’s colonial rule

over the country”. They were away for four months.

Aline moved to the West Coast at the beginning of 1931. Hollywood

was busy while the rest of the country struggled to keep the wheels

of industry rolling. It was where money didn’t seem to be a problem,

and an established actor could be assured of a healthy salary. It

was also still in the early days of talkies and not every star of

the silent era had been able to make the transition to the new

medium. Once characters on film could be heard talking there was

little need for them to indulge in exaggerated expressions and

gestures to make a point. Aline, with her clear diction and

experience of projecting on stage, was ideally suited to acting in

films. Her training in the Method style likewise allowed her to

emphasise feelings through facial variations and bodily positions.

Stangeland outlines the major shift in acting in this way: “As the

production of talking pictures was codified, a new kind of actor and

personality was coming into popular consciousness. This style, which

was to become the dominant form for nearly twenty years, was

primarily declarative. The sub-text of thought and interior life

that had necessarily developed in the best of silent films was –

unfortunately – deemed redundant in a cinema where characters could

now simply say what they felt”.

Despite being separated from her husband for long spells – he had to

remain in New York to look after his architectural commitments –

Aline was determined to make a career in films. And the money was

useful at a time when so many other people were struggling to make

ends meet, and her husband’s business suffered ups and downs as

projects failed to materialise. But she had to face up to the fact

that the studio system, especially at Warner Brothers, was close to

a factory situation. What sold was what was produced. There were

fine films made, often almost in defiance of the realities of the

market, and there were writers, directors, and others who were

sincerely dedicated to the art (and it could be) of film-making. But

there were many more who saw it simply as a job to be completed on

time and within its budget, and with little thought of investing

what they did with imagination or flair. As someone who has spent a

lifetime since the 1940s watching Hollywood films, good, bad and

indifferent, I’ve often been pleasantly surprised at what

could be done with few resources, and on the other hand sadly

disillusioned by how much money was wasted on lacklustre major

productions.

One of Aline’s first films in Hollywood was

Once in a Lifetime which had originally been a stage play by

Moss Hart and George Kaufman. Described by Stangeland as “a play

about the foolishness and vapidity of Hollywood” it had failed when

it was first tried out in Atlantic City. Aline had been in it, but

by the time it was revised and performed on Broadway she was on the

West Coast. She landed a key role in the film, but was initially

nervous about how it would go down with the industry’s rulers. Would

they see the funny side of a satirical view of their habits and

actions, their poses and pretensions? Launched with all the usual

film capital ballyhoo it became a surprise hit. Aline was one of the

stars of the film, and the

Los Angeles Times commented: “The cast are all capable

performers, with Miss MacMahon standing out in a feelingful,

thoroughly warming portrayal of the patient May Daniels”.

Once in a Lifetime

had been produced by Universal, but Warner Brothers were keen to

have Aline sign a contract with them. She eventually did, after

haggling about how much they would pay her. She settled for $850 per

week for a part in Five Star

Final in which she played newspaper editor Edward G .Robinson’s

secretary. Stangeland is enthusiastic about Aline’s work in this

film, limited though her role was, and says she is “playing the

character, not pitching to the audience, and in this way she invites

attention by not inviting it……she presents a real person, not the

creation of a screenwriter - not a construction deigned to impart

mere information and surface emotion to a story. Her emotions seem

real because she is doing what no other actor of the era is doing –

dredging her own past to connect with the feelings of the

character”.

The money was good, especially in comparison with what most people

were earning, or not earning if they were among the growing army of

the unemployed, but Aline was dissatisfied with the roles that

Warner Brothers insisted she take. She was usually praised by

critics for her performances in films like

The Mouthpiece, Weekend

Marriage, and Life Begins,

but none of them involved a major dramatic leading role. Aline was

cast as a kind-hearted café owner who feeds the down-and-outs in

Heroes for Sale, and she

is effective in this part, but it hardly stretched her acting

talents.The main female emphasis was focused on Loretta Young who

Warner Brothers were clearly promoting as a rising young star. The

film itself is not without interest with its grim portrayal of what

life was like for many people during the Depression. There are

scenes of bread lines, hobos being moved on by townspeople who, as

they say, can’t even take care of their own, and policemen who use

threats and violence to deter demonstrators or anyone else they

consider “radical”.

Alina did have what might be called a leading role in

Kind Lady, where she

plays a middle-aged spinster still mourning her fiancé killed in the

Great War, who is conned by the smooth-talking Basil Rathbone into

allowing him into her house and so enabling him to take over her

life. But it’s notable that the studio considered her suitable for

appearing on screen as a somewhat repressed, even dowdy woman. She

just wasn’t seen as conventionally attractive, though photos in

Stangeland’s book indicate that she could be quite striking in

appearance. I suspect that Hollywood didn’t really know what to do

with her because her looks and her age (she was in her thirties when

the films I’ve mentioned were made) eliminated her from

consideration as one of the film capital’s glamour girls. She was

fated to be seen as a character actor and nearly always in a

supporting role. There was one film,

Heat Lightning, described

by Stangeland as a “deliciously tawdry proto film noir”, which

featured her alongside Ann Dvorak and allowed her to develop the

part she played as one of two sisters, both yearning for the same

man, with a greater degree of conviction.

Both Aline and her husband held what might be called progressive

views about the nature of capitalist society, and she was on record

as having spoken favourably in support of left-wing, even communist,

ideals. I think there may have been something of a clash between her

sympathies and the fact that she could earn relatively good money by

acting in mostly mediocre films at a time when there was widespread

poverty and discontent. She was aware of her artistic predicament:

“If I catch myself retrogressing in my work I will quit and to the

Devil with the whole lot of them. But I suppose I’ll go on taking

the money, just the same”.

The couple made a trip to China in 1937 and were impressed by what

they saw there, though one wonders how far they travelled within the

country? Stangeland

describes Aline as “a liberal, Communist-curious citizen”, and says

that she attended anti-Fascist meetings and rallies. But her private

life and her Hollywood career were affected by her husband’s

ill-health. She had to go back to New York to look after him. She

did manage to continue some acting activity by working in radio and

returning to the stage. She starred with John Garfield in

Heavenly Express, a

“light fantasy” that unfortunately failed to attract audiences. She

worked with him again in Out

of the Fog during one of her periodic returns to Hollywood.

Garfield was a proponent of Method acting and, like Aline, had links

to left-wing organisations. This latter fact was to cause problems

for them both.

There were appearances in films in the post-war years. She was with

Montgomery Clift, another graduate of the Method school, in

The Search, and had a

part in the Burt Lancaster film,

The Flame and the Arrow.

But her liberal/left-wing inclinations were noticed as the

anti-communist mood of the late-1940s and early-1950s began to

develop. The Chicago Tribune

newspaper listed Aline as a communist as early as 1945, and

later she would be named by Louis Budenz, a one-time Communist Party

member turned informer. She was also included in

Red Channels, a

publication designed to name anyone with alleged communist

affiliations who was employed in films, television, and radio. It

was used as a reference book by producers and others who hired

actors. Inclusion in it would lead to almost automatically being

blacklisted. It certainly affected Aline’s career and Stangeland

says that she “managed only two film appearances and five television

credits between 1950 and 1960”. One of the films was the 1955

The Man from

Laramie, a Western directed by Anthony Mann and starring James

Stewart, where she played an elderly rancher who befriends Stewart.

It would be interesting to know how she managed to evade the

blacklist for this film and the 1953

The Eddie Cantor Story.

She did obtain work with regional theatre companies in the 1950s,

and in the 1960s she was active in New York with the Repertory

Theatre of Lincoln Center. Her husband died in 1975, and Aline in

1991, aged 92.

It’s difficult to comment on her use of the Method technique because

of the nature of most of the films she was in. She often had little

opportunity to extend her acting beyond the ordinary. It could be

that she was more successful in the theatre but, unlike films, few

plays leave a permanent visual record. We can only wonder, or rely

on written testaments from those who were around at the time, about

what great actors were like on stage.

John Stangeland’s book is not only an informative account of Aline

MacMahon’s life and career. It additionally provides some valuable

insights into how the studio system functioned in the 1930s and

1940s, and what were the problems facing actors who didn’t easily

fit into the kind of neat categories that Hollywood liked. It’s

enlightening about how actors under contract, or even freelancing as

Aline did, had to take what was on offer if they wanted to work

regularly. Film-making was a business and the good went with the

bad. It wasn’t much different in the theatre, and Stangeland quotes

the old-time character actor J.M. Kerrigan who, listening to Aline

complaining about the quality of the films she was involved with,

said: “To hear actors complain about pictures, you’d think that in

the theatre they went from one distinguished success to another. I

found damned few decent plays to do in the theatre, I remember”.

The book is well-researched, has a short but useful bibliography,

and relevant illustrations, some of which show how attractive Aline

MacMahon could be.

|