|

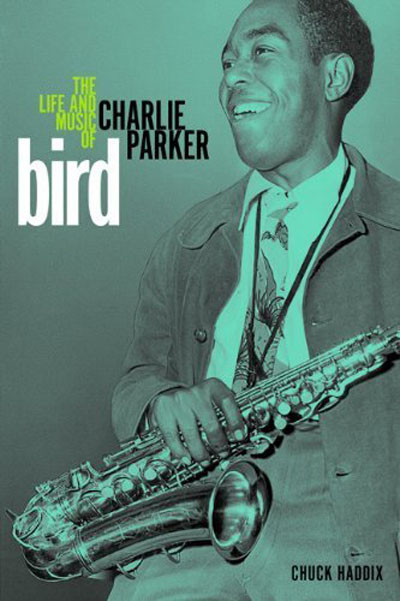

BIRD: THE LIFE AND MUSIC OF CHARLIE PARKER University of Illinois Press. 188 pages. $24.95. ISBN 978-0-252-03791-7 Reviewed by Jim Burns

When Charlie Parker died in 1955 the words “Bird Lives” suddenly appeared on walls around Greenwich Village. They were a testament to the influence he had in the late-1940s and early-1950s not just on musicians, but also on a whole host of hipsters, poets, artists, writers, and others who identified with his music and, in some cases, with his life-style. And the fact that books about him continue to appear fairly regularly almost sixty years since his death is a testament to the power of his music, and also to the way in which his life continues to fascinate. It is valid to ask if there is anything new left to say about the life, even if analysis of the music can continue to intrigue musicians and critics with enough technical know-how to be able to follow the intricacies of his solos. Most listeners, though, will probably just be satisfied to sit back and enjoy hearing Parker. And that in itself can often be an enlightening experience, though one might be hearing a solo that one has heard dozens of times before. There is something about the best of Parker’s work that somehow always seems to be fresh and capable of suddenly alerting the listener to a phrase that one had never noticed before. It’s as if he is still alive and able to change the direction of a solo. Bird lives, indeed. Writing his life may, however, be a different story because previous books have laid down many of the anecdotes, reports, interviews, and other materials that constitute a biography. Someone taking on the task of producing a new outline of Parker’s history needs to be able to come up with fresh details, as well as incorporating the existing ones into an account that will hold the attention. Parker was born in 1920 in Kansas City, a wide-open place that was under the control of Tom Pendergast, a corrupt politician whose policy was to let gambling, drugs, alcohol, and prostitution thrive. To be a bit more specific, Parker was born in Kansas City, Kansas, and it was Kansas City, Missouri, that became known as “The Paris of the Plains.” Once he started to take an interest in music it didn’t take him long to find his way to the clubs and bars where jazz musicians congregated. The fact of the Missouri Kansas City night-life offering employment for musicians meant that it was a place which attracted them in large numbers. Parker’s musical education was not an easy one, nor was it in any way formal. In a sense he learned on the job once he became proficient enough on his instrument to obtain employment in local bands. And there are stories about how he was chased off the stand when he tried to sit in at jam-sessions before he’d developed his technique and ideas enough to obtain any sort of respect from established players. One thing that becomes obvious is that he never allowed the rejections to deter him from working even harder at improving his technique. He’d disappear for a while and then re-appear and surprise everyone with how much he’d forged ahead. If Parker was steadily developing as a musician he was also showing a propensity to involve himself in other activities, primarily those involving drugs, alcohol, and women. Married at the age of fifteen, a father not much later, and addicted to heroin when he was sixteen, he’d also worked out how to charm people into letting him have his own way and so allow him a kind of domination of any situation. His first wife, Rebecca, thought that part of his problem was that his mother indulged him. As Chuck Haddix puts it: “Spoiled by Addie, Charlie became accustomed to getting what he wanted by manipulating others with his considerable charm.” After working with a number of local bands, and already building up a reputation for unreliability when it came to turning up on time or even turning up at all, he decided to head for Chicago as the first stage on a journey to New York where he hoped to meet up again with Buster Smith, a saxophonist he’d known and idolised in Kansas City. There’s a colourful account by Billy Eckstine in Haddix’s book of how Parker astounded listeners when he borrowed Goon Gardner’s saxophone and, in Eckstine’s words, “blew so much until he upset everybody in the joint.” Parker was ragged and hungry and Gardner took him home, gave him clothes, lent him a clarinet, and found a few jobs for him until “one day he looked for Bird, and Bird, the clarinet and all was gone.” It wasn’t the last time that Parker would repay kindness by disappearing with someone else’s instrument. He did eventually get to New York where Buster Smith took him in until Smith’s wife tired of his habit of sleeping in their bed with his clothes and shoes on. After joining in jam sessions at Clark Monroe’s Uptown House, an after-hours club that, along with Minton’s Playhouse, is often referred to as somewhere where the musical ideas that later became known as bebop were developed, Parker returned to Kansas City for a time. And he was offered a job with Jay McShann’s band. It was while he was with McShann that he first met trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. Another trumpeter, Buddy Anderson, later recalled that the meeting wasn’t a total success in that Gillespie wasn’t impressed by what he heard of Parker’s playing. Gillespie himself remembered it differently: “I was astounded by what the guy could do,” and he added that he realised that he and Parker were heading in the same direction, musically. There are recordings, both non-commercial and commercial, from this period and Parker can be heard soloing on some of them. I don’t want to enter into any sort of extended analysis of his playing at this time, but Haddix does refer to his “formidable technique and maturity” when discussing one solo, and that does seem to sum up how he was performing then. When McShann obtained a recording contract with Decca Parker’s work began to be heard by a wider audience, though only in the form of short solos. The Decca producers weren’t too keen on the more-adventurous originals that the McShann band had in its book and preferred to have it recording blues and boogie-woogie numbers, often with a vocalist involved. It’s worth noting that some solos that were for a long time thought to be by Parker were actually by John Jackson, Parker having “showed up high and off his game” at the recording session. It wasn’t much later that McShann grew tired of his chaotic behaviour and fired him after he’d collapsed on stage at a theatre in Detroit. Prior to that the McShann band had worked at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem and broadcasts from that venue had further brought Parker’s work to the notice of musicians. Haddix quotes trumpeter Howard McGhee, then with Charlie Barnet’s band, recalling how the altoist’s work got the attention of all the musicians when McGhee turned on the radio in the dressing room at the theatre where they were working and tuned in to a broadcast by McShann. Parker’s reputation for erratic behaviour was well-known but Earl Hines decided to hire him anyway, arguing that he would “make a man” out of him. By this time Hines had a big-band which was a home for a number of young musicians who were progressive in their views. Dizzy Gillespie was with Hines for a time, along with Benny Harris, Shorty McConnell, Gail Brockman, and Benny Green. Some of these names may not arouse much comment now, but they have a place in the history of how bebop developed in the 1940s. Hines never did manage to make Parker behave himself and they eventually parted company. It was during this period that Parker met and married another woman despite still being legally married to his first wife. The marriage didn’t last long, and years later Geraldine, the second wife, when involved in litigation over Parker’s estate, said: “When I married him, all he had was a horn and a habit. He gave me the habit, so I might as well have the horn.” There’s an interesting explanation offered by Haddix about why, in the war years, club owners along 52nd Street in New York suddenly found it advantageous to hire small jazz groups rather than dancers and other kinds of entertainers. A 20% cabaret tax was imposed, primarily to try to discourage prostitution and so reduce the spread of venereal disease among servicemen. Instrumental groups were not subject to the tax. So, the Club Downbeat, the Three Deuces, the Spotlite, and the Onyx Club became, for a time, centres of excellence in terms of the jazz on offer. Bebop and the musicians who were performing it began to get a hearing in New York outside places like Minton’s and the Uptown House where they gathered to play after hours. The boppers also began to be heard on records, albeit sometimes in strange company. Parker, for example, recorded with an old vaudeville entertainer named Rubberlegs Williams, and there’s a story that, during the session, Williams mistakenly picked up Parker’s coffee which had been liberally laced with Benzedrine. The result was that Williams began to behave in a boisterous manner that affected his singing. If Haddix is right he had to be replaced by trombonist Trummy Young who took over the vocals. I think one of the main points to be made here is that, at this point in his career, Parker hadn’t become sufficiently established to have his own group. He recorded with guitarist Tiny Grimes and trombonist Clyde Bernhardt in settings that somewhat limited his improvising capabilities, though a couple of the Grimes tracks do feature him to good advantage. Matters began to look up early in 1945 when Parker and Dizzy Gillespie got together to record for one of the many small labels that had sprung up during this period. It’s true that the group was far from a pure bebop line-up, with the rhythm section at both the dates involved tending to lean more towards a swing rather than bop feeling. But Parker and Gillespie performed well on tracks like Shaw’ Nuff and Hot House which are now enshrined in the history of modern jazz. Haddix describes the combination of Gillespie and Parker as like a marriage of convenience in that they shared musical ideas but had little in common as people. Gillespie led a relatively “traditional lifestyle,” with his flamboyant behaviour on-stage being a deliberate act that was meant to attract attention, whereas Parker’s serious on-stage manner, at least when he was sober, was a cover for a personal life that could only be described as tumultuous. By late-1945 bop had gained enough attention for Billy Berg, a club-owner in Los Angeles, to hire Gillespie to bring a group to California. Dizzy included Parker in the musicians he chose, but also brought along vibraphonist Milt Jackson because of the altoist’s unreliability. Parker had by then made his first records as a leader at a somewhat disorganised date that nevertheless produced tracks which were to prove influential. On Ko Ko, a fast piece based on Cherokee, Parker played some dazzling improvisations that impressed numerous young modernists, while the slower Now’s The Time had a title that almost summed up the feelings of those same would-be boppers. There are conflicting reports of how many West Coast fans responded to the arrival of Parker and Gillespie. Some accounts say that they were received warmly, others that audiences soon stayed away from Billy Berg’s club. I would guess that the initial reaction was favourable largely because the customers were mainly sympathetic to bebop, often being musicians themselves or fans with a prior awareness of what to expect. Later, however, business slackened and the people who did come were not likely to spend much money, being happy just to nurse a single drink and listen to the music. There is a mini-history that could be written about events in California, but suffice to say that when Gillespie and the others returned to New York Parker, deep in the throes of addiction and suffering because he couldn’t obtain the drugs he needed, stayed in Los Angeles and slowly began to fall apart. He played in local clubs, was helped by trumpeter Howard McGhee, and was hired for a record session by Ross Russell, a record-shop owner who had formed a company, Dial, so as to be able to cut some sides by Parker. The first session that Russell recorded was a disorganised affair and ran well over time, largely due to Parker antagonising certain musicians he had originally intended to use and so having to bring in last-minute replacements who were unfamiliar with the tunes he wanted to record. But some good music was eventually produced, with a young Miles Davis and tenorman Lucky Thompson alongside Parker in the front-line. A second session, however, a few months later, was a disaster. Parker was unable to obtain heroin in Los Angeles and was drinking heavily and in such a poor condition that he was virtually unable to play on faster numbers like Max is Making Wax and Bebop, while the slower The Gypsy and Lover Man found him almost stumbling through each performance. Had it not been for the presence of Howard McGhee and pianist Jimmy Bunn the records might have been complete write-offs, but Ross Russell decided to release them, an act for which Parker never forgave him. Lover Man has become something of a symbol of a great artist cracking up and the recording session was celebrated, if that’s the right word, in a short story, “Sparrow’s Last Jump,” by Elliot Grennard, a journalist who happened to be a witness to the events that took place. Parker later broke down completely and was committed to Camarillo State Hospital, where he remained for several months. On his release he resumed recording for Dial, made some excellent records, and then went back to New York where he soon formed a group which included Miles Davis and pianist Duke Jordan. He was still contracted to Dial, and did continue to record for that label, Ross Russell even moving to the East Coast so he could supervise the sessions, but Parker also managed to slip in recording dates for Savoy. There is, as a consequence, plenty of evidence available of his playing during this period, and as the years after his death passed live recordings of his group playing in clubs like the Royal Roost, Café Society, and Birdland were released on a variety of labels. The line-up of his quintet altered, with trumpeters Kenny Dorham and Red Rodney replacing Davis at one time or another. Listeners with a less than fanatical interest in Parker need to be wary of some of this material as it was often recorded in less than perfect circumstances and the recording equipment was sometimes switched off when he wasn’t soloing. Parker’s reputation was probably at an all-time high during this period, though he continued to lead what can only be described as a self-destructive life-style. He made trips to Paris and Sweden and was feted in both places. While in Paris he was introduced to Jean-Paul Sartre and other French writers and intellectuals. Back in New York he recorded for Mercury under the supervision of Norman Granz, a man who believed that performers like Parker ought to be treated with respect and receive proper payment for their services. But Granz also had a tendency to try to direct musicians into recording material that didn’t necessarily always suit their musical personalities. Parker thus was recorded with strings, with a big-band, with Latin-American rhythm sections, and even on one occasion with a choir and orchestra. The results were sometimes variable, but Parker was always worth listening to and there is evidence to show that he was happy to make these records, not only for the money he badly needed, but also because he aspired to the sort of attention that he thought a wider approach than his quintet allowed him might attract. In the early 1950s Parker often worked as a single, travelling to a variety of towns and cities and playing with local musicians who, it has to be said, were not always of a calibre likely to push him into doing more than performing capably. Some engagements were near-disastrous, as when he took a group to Montreal and the club owner terminated their appearance after a few days. The musicians were said to be scruffy and had obviously not rehearsed before arriving. The pianist, Harry Biss, was particularly noted as being “always in a fog,” and had to be replaced by a local musician. I’d guess that Parker had selected most of the musicians from a clique of drug users he ran with in New York. The drummer, Art Mardigan, even turned up without a kit and had to borrow one. Reading Haddix’s book it’s obvious that the final years were sad ones. Parker was never free of drugs, even if he did occasionally try to reduce his intake. He drank heavily, had a domestic life that had its tragedies, and was in and out of scrapes of one kind or another. He was, at one point, even banned from Birdland, the club named in his honour. He tried to commit suicide, was found homeless and wandering the streets and taken in by someone who recognised him, and was permanently financially impoverished. He could still play well as late as 1954 and recordings made at the Hi-Hat Club in Boston during that year are worth hearing, though it’s quite obvious that he’s relying on material he was completely familiar with and probably never extends himself enough to say anything new. Obviously, he was sometimes working with musicians he had perhaps never met before, so a reliance on some standard tunes would have been inevitable. And, though it may be a purely personal opinion, it seems to me that listening to Parker, even when he was not necessarily at his best, is still an exciting experience. The story about him dying in Baroness Kathleen Annie Pannonica Rothschild de Koenigswarter’s apartment in New York in 1955 is too well-known to be repeated here, but it fits in with the other activities of a man who never did anything in half-measures. I’ve deliberately compressed the details of Parker’s life in his last few years, but Chuck Haddix provides a more detailed account for those who are keen to learn more. Does his book add to what we already know about the man and his music? I think the answer is “yes,” and he manages to give us the information we need in a reasonable number of pages. In an age where biographies often run to 500 pages and more, and biographers seem to feel the urge to provide us with information we could well do without, it’s a pleasure to read a book that sticks to the essentials and does it in a well-written and careful way. A little bit of musical knowledge might be useful when reading the occasional musical examples that Haddix refers to, but it’s not a problem if you are someone who just likes to listen to music and doesn’t think it essential to recognise all the technical details about a performance. Just sit back, put a Parker CD in the machine, and read what Haddix has to say. “Bird Lives.”

|