|

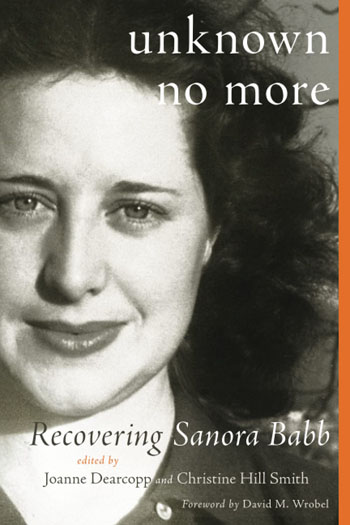

UNKNOWN

NO MORE: RECOVERING SANORA BABB

Edited by Joanne Dearcopp and Christine Hill Smith

University of Oklahoma Press. 209 pages. £21.50. ISBN

978-0-8061-6936-1

Reviewed by Jim Burns

At some point in the early-1960s I was in Collett’s Bookshop on

Charing Cross Road and bought an anthology called

The American Century: 34

Short Stories by 34 American Authors. It was edited by Maxim

Lieber and published by Seven Seas Books in 1960 from what was then

East Berlin. Its left-wing leanings were plain to see. Lieber had

been a literary agent in New York, but when the Alger Hiss/Whittaker

Chambers confrontations hit the headlines in the late-1940s he was

accused of being a Soviet spy and fled to Poland. And many of the

writers in the anthology were identifiable as having left-wing

inclinations. A few – Albert Maltz, Alvah Bessie, Philip Stevenson –

had been caught up in the anti-communist purges in Hollywood, and

others – Jack Conroy, Nelson Algren, Ben Field – had written radical

novels.

A name that stood out was that of Sanora Babb. I knew little about

her beyond the notes in the anthology, and those in

Cross Section 1945 (L.B.

Fischer, New York, 1945)

that I’d come across in a second-hand bookshop and which had a story

by Babb. Again, the

liberal/left-wing leanings of the editor, Edwin Seaver and many of

the contributors were in evidence. All

this was long before the Internet and I didn’t follow up on finding

out more about Babb, though I came across references to her in books

by Alan Wald and others. There was a story in

Writers in Revolt :

The Anvil Anthology 1933-1940

(Lawrence Hill, Westport,1973) reprinted from a 1934 issue of Jack

Conroy’s magazine, The Anvil.

Curiously, she was omitted from what is otherwise an excellent

collection, Writing Red: An

Anthology of American Women Writers 1930-1940, edited by

Charlotte Nekola and Paula Rabinowitz (Feminist Press, New York,

1987).

More recent years have seen a revival of Interest in Babb and

reprints of most of her work. So, who was she? She was born in 1907

in Oklahoma and grew up there and in Colorado where the family moved

to when she was seven. They lived with Babb’s grandfather in a

one-room dug-out. Her

father, a failed farmer, was a professional gambler. Babb’s early

education seems to have been sporadic, though she did eventually

leave school with qualifications, taught at a one-room schoolhouse,

and obtained a job on a local newspaper. It’s worth noting that

“Babb’s grandfather took the

Appeal to Reason, a weekly socialist newspaper out of Kansas”.

By 1929 she was living in Los Angeles, where she experienced

“poverty and often homelessness” while writing poems and stories

that were published in magazines and newspapers, especially those

with a left-wing policy. The collection,

The Dark Earth and Selected

Prose from the Great Depression (Muse Ink Press, Old Greenwich,

2021) has material from the 1930s, with publications such as

The Anvil, New Masses,

Outlander, and The

Midland credited. It’s doubtful that she earned much from these

magazines and she took various jobs, including one “writing copy for

the Warner Brothers radio station KFWB”.

She was also mixing with many young writers such as Tillie Olsen,

Carlos Bulosan, William Saroyan, John Howard Lawson, and Ray

Bradbury. Saroyan and Bradbury both became successful fiction

writers, Lawson was a playwright, screenwriter and, as a leading

communist in Hollywood, later one of the Hollywood Ten. Olson

struggled to balance writing with family and political involvements.

Bulosan was a Filipino-American who was encouraged to write by Babb

and her sister, Dorothy. His

American Is in the Heart (Penguin Books, New York, 2019) is a

classic account of what it was like to be drawn to American ideals

but come up against the violence and prejudice that immigrants

experienced. The account of working in the fields and factories of

Southern California parallels some of Babb’s stories of the harsh

practices that applied in such occupations. Attempts to form unions

and strike for better pay and conditions could result in injuries

and even deaths as local police, vigilante groups and hired thugs

attacked strikers and their families.

Babb’s “immersion in the milieu of diversely radical and untamed

artists and writers who were pulled to the Communist-led John Reed

Clubs in the early 1930s” quickened her commitment to communism as a

possible solution to the social, economic, and political problems

then evident in America and the world at large. In 1935 she attended

the First American Writers Congress in New York, an event organised

by the League of American Writers, a Communist “front” organisation.

She would have heard speeches by, among others, Malcolm Cowley,

Waldo Frank, James T. Farrell, John Dos Passos, Meridel Le Sueur and

Kenneth Burke.

And there was Jack Conroy talking about “The Worker as Writer” and

offering the opinion that “To me a strike bulletin or an impassioned

leaflet are of more moment than three hundred prettily and

faultlessly written pages about the private woes of a gigolo or the

biological ferment of a society dame as useful to society as the

buck brush that infests Missouri cow pastures and takes all the

sustenance out of the soil”. A fictional account of the Conference

can be found in Farrell’s novel,

Yet Other Waters

(Vanguard Press, New York, 1952), where Conroy is satirised as a

somewhat blustering and not very intelligent novelist and activist.

A trip to Russia in 1936 persuaded Babb to take a positive view of

communist achievements. She claimed that no restrictions were placed

on her movements and she was allowed to talk freely to the people

she met. In “Dr Fera of Moscow”, a piece published in the left-wing

magazine The Clipper in

1941, she wrote about the fact that “In Russia, women were competing

equally with men in every field of work. I rode on a train

completely run by women. I talked to a 22-year-old woman engineer

who was directing a crew of a hundred men in the construction of a

bridge. I visited the home of a collective-farm woman, who, freed of

the drudgery of housework and baby-raising by co-operative effort

and the amazing social care of children, had in middle-age become an

expert in horticulture”. She also wrote about Dr Fera, a peasant

girl who, after many misadventures, was encouraged to train to

become a doctor.

In 1938 she took the plunge and joined the American Communist Party.

It was also the year that she volunteered to work in one of the

California Migrant Camps set up to try to provide basic forms of

sanitation and housing for at least some of the families who had

fled from the great dust storms in the Midwest. Many of them had

lost everything as the drought, winds, and storms destroyed their

farms. Interestingly, the

Camp she worked at was the one under the supervision of Tom Collins,

and it was also visited by John Steinbeck when he was writing

The Grapes of Wrath, his

powerful story of the plight of the “Okies”, the name given to the

migrants. Babb herself wrote about them in her novel,

Whose Names Are Unknown,

which was initially intended for publication by a major New York

house, but was dropped when Steinbeck’s book appeared and became a

popular success. The would-be publishers of Babb’s book did not

think there would be a viable market for another novel on the same

subject.

Babb worked for The Clipper

and The California

Quarterly, both radical magazines, continued to write, and

helped run a restaurant with her husband, the noted Chinese-American

Hollywood cameraman, James Wong Howe. When the anti-communist purges

started in the film capital in the late-1940s and early-1950s, Babb

immediately fell under suspicion. As a Communist Party member and

contributor to left-wing publications, her name and activities would

have been known to the FBI and HUAC. She moved to Mexico around 1950

in order to draw attention away from Howe. Quite a few Americans

found it convenient to spend time in Mexico as HUAC widened its

investigations and the mood in America turned to one of hostility

towards anything that smacked of Un-Americanism. What that meant

precisely could depend on circumstances, and it was used as a weapon

against the unconventional not only in politics but also in the arts

and even personal behaviour.

Like many people, Babb drifted away from the Communist Party in the

early- 1950s. She had become disillusioned by the levels of

conformity and control, and even earlier, in 1946, she had expressed

support for Albert Maltz when he was condemned by Party hardliners

for suggesting that writers should be free to choose their own

topics and how to write about them. She continued to write and

publish poems and short fiction in a variety of magazines. And there

were extended works such as

An Owl on Every Post (Muse Ink Press, 2012) and

The Lost Traveler (Muse

Ink Press, 2013). Her

1930s novel, Whose Names are

Unknown, continued to be hidden away until renewed interest in

her work caused it to be “discovered” and finally published by the

University of Oklahoma Press in 2004.

It perhaps could be said of Babb’s work as a whole that she

essentially located most of it in the period prior to 1950. Her

childhood in the Mid-West and her experiences in the 1930s seem to

me to encompass many of her stories, memoirs, and longer works.

Whose Names are Unknown

is in two parts, the first of which deals with hard times in the

Oklahoma Panhandle, and the second with the struggle to survive in

California. The “Okies” (not all of them from Oklahoma) follow the

fruit and other harvests, often residing temporarily in company

shacks and forced to shop at company stores. When they try to

organise and strike for better wages and conditions they’re harassed

by police and company guards, and evicted. There is a vivid

description of a union activist being falsely accused of getting

“fresh” with a local’s wife and subjected to a beating by

vigilantes.

The same sense of violent oppression is evident in “The Terror”, an

account of a secret night-time visit to striking miners in New

Mexico which originally appeared in a 1935 issue of

International Literature,

published in Moscow. It has recently been included in

The Dark Earth and Selected

Prose from the Great Depression. This is an excellent selection

of fiction and reportage from a range of magazines. A story, “A Good

Straight Game”, seems to have its basis in the activities of Babb’s

father as the male character, despite previous promises, succumbs to

the lure of a game of cards. Another, “The Old One”, from

The Midland in 1933,

tells of the sudden death of an old man and how the neighbours come

together for his funeral.

The non-fictional items include a piece about the way in which those

working as “extras” in Hollywood struggle to survive in the face of

low wages and fierce competition for the available work. But should

anyone think that all of Babb’s writing focused on social and

political matters, they might have a look at the story, “Femme

Fatale” which, to my mind, would not seem out of place in a

collection of New Yorker

short fiction from the Forties and Fifties. It was actually

published in Masses &

Mainstream, a communist journal, in 1954. They might also look

at the stories in Cry of the

Tinamou (Muse Ink Press, 2021), some of which appeared in widely

circulated publications like

Seventeen and The

Saturday Evening Post.

Unknown No More

is a collection of essays looking at different aspects of Babb’s

writing. I haven’t wanted to single out individual pieces because

they all seem to me of value in terms of drawing attention to an

under-rated writer. I am tempted to refer to Christine Hill Smith’s

“The Radical Voice of Sandra Babb” because it reflects my own

interest in what Babb did. But that would be unfair to the other

contributors and to Babb who clearly wanted her writing to encompass

more than the specific world of left-wing politics and proceedings.

She seems to me a writer well worth reviving.

|