|

ANYTHING THAT BURNS YOU: A PORTRAIT OF LOLA RIDGE, RADICAL POET By Terese Svoboda Schaffner Press. 627 pages. $29.95. ISBN 978-1-93618296-1 Reviewed by Jim Burns

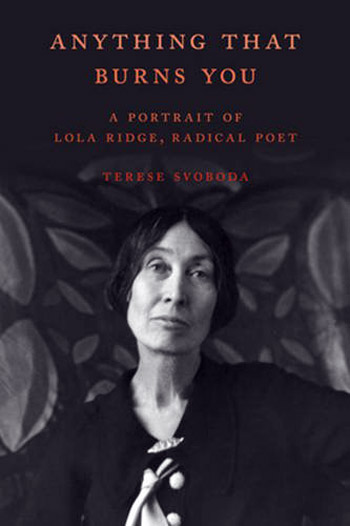

Lola Ridge? Hardly a name that is likely to arouse a reaction from most readers of poetry in the UK, or for that matter, in the USA. And yet, in her day, she certainly had many positive responses to her books and she was considered to be something of an adventurer in terms of her subject-matter and sometimes her technique. But, like so many poets, she quickly faded from sight after her death in 1941, and it was only in more-recent years that her reputation has begun to be re-examined. Left-wing literary historians like Alan Filreis and Carey Nelson have written about her, and Robert Hass included poems by her in his anthology, Modernist Women Poets, placing Ridge alongside Marianne Moore, Gertrude Stein, Mina Loy, and others. My own initial encounter with Lola Ridge’s poems came in the early-1960s when I picked up a copy of Louis Untermeyer’s Modern American Poetry (the 1932 edition) from a second-hand bookstall. Untermeyer included excerpts from Ridge’s long poem, The Ghetto, along with some shorter poems, and generally spoke highly of her work. After that, I occasionally came across references to Ridge in books like Albert Parry’s Garrets and Pretenders: A History of Bohemianism in America, Alfred Kreymborg’s Troubadour, Harold Loeb’s The Way it Was, and Gorham Munson’s The Awakening Twenties: A Memoir-History of a Literary Period. Mostly, these references related to Ridge’s links to little magazines, but they intrigued me because I had an interest in the history of such publications. This, of course, was long before the advent of the internet, so tracking down information about Ridge, or any of her books, wasn’t easy. And no-one, before Terese Svoboda, had written a biography of her. Lola Ridge was born in Dublin in 1873. Her parents separated and her mother and Lola emigrated to Australia in 1877. At some point in the late-1870s or early-1880s they moved to New Zealand, where they lived in poverty until her mother re-married. Lola’s stepfather was an unstable personality and was eventually committed to an asylum. Lola had shown an aptitude for painting and writing and published her first poem when she was eighteen. She married in 1896 and had a son who died and a second son in 1900 who survived. Finding New Zealand stifling in its provincialism she took her son and moved to Australia in 1903 to study art. She soon fell in with members of Australia’s bohemia, including the painter, Julian Ashton, who she possibly modelled for. Svoboda provides details of Ridge’s activities at this time, and Tony Moore’s Dancing with Empty Pockets: Australia’s Bohemians has information about Ashton and the Sydney bohemia that she would have experienced. She was also writing and contributed to the Sydney Bulletin, a well-regarded publication with a wide circulation. But she knew that she needed to get away from Australia and, acting with a certain amount of subterfuge to hide her intentions from her husband, she took her son and in 1907 boarded a ship for America. She was in her mid-thirties, but would always claim to be ten years younger. Landing in San Francisco she began to circulate among the city’s bohemian fraternity. Her first poem to be published in the United States appeared in 1908 in a publication that had featured Jack London and Willa Cather. But it was also in 1908 that she placed her son in an orphanage and sailed for New York. It was, she knew, where she would have to be if she was to establish a firm literary identity. It took time for her to start doing that and, to earn money, she worked at various jobs, including probably modelling. She also wrote several stories – “potboilers,” as they were usually referred to – for popular magazines in order to pay the rent and eat. She got to know the famous anarchist, Emma Goldman, and published poetry in Goldman’s magazine, Mother Earth. In 1910 she met David Lawson, who was to be her companion for many years. And she got involved with the Ferrer Centre, an anarchist establishment which was named for Francisco Ferrer who had been executed in Barcelona for his alleged part in advocating a general strike and insurrection against a war in Morocco. It’s possible that Ferrer had been targeted by the authorities as much for his creation of what were termed Modern Schools which attempted to educate children without recourse to state or religious authority. Ridge became manager of the Ferrer Centre, which was frequented by artists such as Robert Henri and George Bellows, who provided free art lessons, and poets like Edwin Markham, famous for “The Man with the Hoe,” and Harry Kemp, known as “The Hobo Poet.” Others who were often in the Ferrer Centre were Eugene O’Neill, John Reed, Hutchins Hapgood, and Hippolyte Havel, later to be immortalised as Hugo Kalmar, the drunken anarchist in O’Neill’s great play, The Iceman Cometh. Ridge was certainly mixing with a lively crowd of bohemians. Will Durant, who met Ridge around this time when he was asked to head a Modern School that was being planned, described her intensity. She was, he said, a “ fragile-looking poet with dark hair and eyes that matched her plain black dress.” It’s certainly a description that fits the photo of Ridge on the front cover of this book. Durant went on to say, “Every word she spoke dripped with feeling,” and “I liked her so much, after a few minute with her, that I was prejudiced in favour of anything she might ask.” It’s worth bearing Durant’s words in mind when considering the way in which Ridge could later always find people to support her financially and otherwise. Ridge and David Lawson eventually left the Ferrer Centre after a disagreement with Emma Goldman. To quote Will Durant again, this time on the subject of Goldman: “There was something of the stern authoritarian in her which made a strident discord with her paeans to liberty.” They travelled around for some years and, while in New Orleans, Ridge sent for her son to join them. But she later left him “in a Detroit boarding house, never to see him again.” It’s difficult to know why Ridge and Lawson acted like they did. Teresa Svoboda several times refers to Ridge’s possible feelings of guilt at the way she had treated her son. But I’m not convinced she offers any suitable explanation. And she provides a list of other women poets who similarly abandoned or neglected children they had, and suggests that male poets would not be taken to task if they behaved in the same way. She could be right. It may well be, though, that both men and women writers and artists can be ruthless if they feel that the development of their talents is being burdened by the presence of children. Whether or not their behaviour can be excused is another matter. Back in New York, Ridge published poems in several prestigious publications, including The Dial, Poetry, Others, and the Literary Digest. And, in 1918 came the publication of The Ghetto and Other Poems, a book that brought her to the forefront of contemporary American poetry. It was the title poem, with its vivid descriptions of life among poor Jews on the Lower East Side, that caught everyone’s attention. Ridge was not Jewish herself, despite what many people inevitably thought, and there was, in later years, some dispute about how much she knew about the Jews and their lives. Her poem does come across as convincing, but David Lawson was quoted as saying, albeit long after the poem appeared, that Ridge had very little experience of the Ghetto until a Jewish acquaintance, Konrad Bercovici, took her on a tour of the area. It’s perhaps futile to argue about this. The poem seemed to evoke both the sights to be seen, the voices to be heard, the atmospheric mixture of poverty and rebellion, in a vigorous free verse that, Svoboda claims, “displays an intimate knowledge of life on Hester Street, and in the sweatshop.” Reactions were generally positive. It wasn’t that the lives of Jews in New York were unknown. There had been various books on the subject published, and Yiddish poets like Morris Rosenfeld had been active for some years. But the fact that many of them wrote only in Yiddish limited their possible readership. It may have been that Ridge, writing in English and in a thoroughly modern style, just hit the right note at the right time. There were other poems in Ridge’s book and one, in particular, “Frank Little at Calvary,” pointed to her commitment to radical politics. Little was an organiser for the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and had led strikes and spoken out against American involvement in the First World War. In August, 1917, he was kidnapped and murdered by vigilantes in Butte, Montana. Ridge’s poem, as its title indicates, saw his death in almost-religious terms. Svoboda interestingly refers to another poet, active at the time and now, like Ridge, little-known. Arturo Giovannitti also wrote poems in a loose, long-lined style that celebrated radicals and other dissenters from the mainstream. His poem, “The Walker,” written while he was in prison on a murder charge that had been rigged by the police, was well-known and still retains its power when read now. Svoboda describes his poems as “conflating Christian beliefs with proletarian morality.” Ridge was active in many ways. She became one of the editors of the Birth Control Review, the magazine of Margaret Sanger’s organisation, and was also involved with the poetry magazine, Others, which had been founded by Alfred Kreymborg. It was one of the publications promoting the new in American poetry, and printed work by William Carlos Williams, Mina Loy, Man Ray, Louise Bogan, T.S.Eliot, and many others. Svoboda says that Ridge had a weekly salon in her one-room apartment at which contributors to Others got to know their fellow-poets. But, as so often happened with little magazines, the money and energy began to run out after a few years. Kreymborg’s lively and colourful autobiography, Troubadour, speaks warmly of Ridge and her parties, and also says that it was her efforts which kept the magazine alive for a little longer than it would have been otherwise. There were fictional descriptions of Ridge’s parties in Robert McAlmon’s Greenwich Village novel, Post-Adoloscence. And the now-forgotten and ill-fated Emmanuel Carnevali wrote about them in his A Hurried Man, where a chapter re-creates a speech he made at one of them. Kay Boyle, in the preface to Carnevali’s book when it was finally published in America in 1967, many years after his death, recalled that it was Lola Ridge who first told her about his work. Ridge and David Lawson had lived together for ten years when they decided to get married. Ridge had never divorced the husband she had in New Zealand, but it was unlikely that evidence of the marriage would have existed in the United States. The marriage to Lawson may have been a matter of convenience that would enable her to obtain American citizenship. The notorious Palmer Raids were taking place and foreign-born radicals were being rounded up and deported. It’s more than likely that Ridge would have come to the attention of the authorities for her activities with the Ferrer Centre and her associations with Emma Goldman, Margaret Sanger, and other social and political activists, as well as her radical poems. There doesn’t appear to be any evidence to show that she was investigated, but the marriage was probably a precaution against deportation. Ridge was too fiercely independent to welcome being legally tied to any man, and Lawson was an avowed anarchist, so the institution of marriage was hardly likely to have met with their approval otherwise. Ridge’s second book, Sun-Up, was published in 1920, and had poems dedicated to Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman (Goldman’s companion and fellow-anarchist), and James Larkin, the Irish labour leader who had been active in the Dublin strikes and lockouts of 1913. She also became the American Editor of Broom, a magazine started by Harold Loeb. He achieved some notoriety a little later when Ernest Hemingway based the character of Robert Cohn on him in The Sun Also Rises. Loeb was part of the American expatriate community in Europe, a fact that was to lead to some dissension between him and Ridge as they disagreed on whether or not the magazine should have an American or European slant. Added to which were the practical problems of communication when Loeb was on the move in Europe and Ridge was in New York. It was never likely to lead to the smooth running of Broom. Svoboda’s account is sympathetic to Ridge’s situation, but Loeb’s autobiography, The Way it Was, offers a different view and he claims that he had doubts from the beginning about Ridge’s suitability for the role of American Editor. He said that he suspected that her “interest was primarily editorial and that her hair-trigger judgements and dogmatic opinions would raise hob with Broom’s editorial policy.” Ridge would eventually resign her position over the inclusion of Gertrude Stein’s work in Broom. She disliked Stein’s writing and thought it likely to be “on the rubbish heap” in a few years. Loeb himself didn’t much care for Stein’s work, on the whole, but considered that it was “an influence,” and therefore ought to be represented in the magazine. There is a suggestion in Svoboda’s account that some of the problems may have arisen because Ridge asserted her right to make editorial decisions, whereas she, as a mere woman, had been expected to largely confine her role to administrative tasks. But she had performed those quite well and had increased the circulation figures for Broom. It’s perhaps significant that when she left the American office of the magazine it was taken over by Matthew Josephson and Malcolm Cowley, and Broom closed down shortly after, Ridge moved on to the New Masses in the 1920s. This was a publication that followed on from The Liberator and, before that, The Masses, the magazine suppressed by the U.S Government in 1917 because of its anti-war stance. The New Masses, though initially independent, was soon firmly under the control of the Communist Party, and Mike Gold, who became the leading light of the proletarian movement, set the tone of the magazine. Svoboda quotes from an attack he made on Gertrude Stein, in which he said that her works “resemble the monotonous gibberings of paranoiacs in the private wards of asylums….The literary idiocy of Gertrude Stein only reflects the madness of the whole system of capitalist values.” I don’t suppose Lola Ridge would have been bothered by Gold’s attack, though she might not have approved of his language. She was offered the position of managing editor of New Masses, but turned it down and, instead, became a contributing editor. She no doubt knew that, as “an individualist,” (her own self-description), she would not fit in easily with Gold’s increasingly Party-line approach. In 1927 she brought out what was her most political book, Red Flag, though she continued to maintain that she had little or no interest in dogma or ideology. Some of the poems had titles like “Moscow Bells,” but that didn’t indicate any allegiance to communist principles. David Lawson later recalled that they had celebrated the Russian Revolution when it occurred, but so did many other people, not all of them necessarily communists. And Ridge told friends that she had sent a copy of Red Flag to Trotsky. What she didn’t realise was that, by 1928 or so, his influence was waning and Stalin’s was rising. Ridge was by this time well into her fifties, though she continued to claim she was ten years younger. Her health wasn’t good, she was said to have separated from Lawson, and was living in poverty. According to Svoboda, Ridge suffered from migraine attacks, stomach trouble, and other ailments. Always painfully thin, it’s probable she may have been anorexic. And possibly may have been showing signs of tuberculosis. On the other hand, there were suggestions that her illnesses could have been a way of attracting attention, of gaining sympathy, or finding excuses for not working. It was noticeable that she seemed to quickly recover if opportunities to travel arose. And she easily found people to support her financially or offer her free accommodation. One problem that was caused by her ill-health was that she became addicted to various non-prescribed drugs, including one called Gynergen. It’s interesting to note that she often depended on David Lawson to obtain this and other similar medicines for her, despite his being some distance away when, for example, she was a resident at the Yaddo artists’ retreat. Unlike other writers and artists she seemed able to persuade the staff there to let her stay more than once. Her ill-health didn’t stop her from being present and arrested at the demonstrations in Boston against the executions of Sacco and Vanzetti. They were two Italian-born anarchists who were alleged to have held up a payroll delivery during which two guards were shot and killed. It was suggested that they had been arrested simply because they were anarchists and that there was little hard evidence to show that they had been involved in the robbery. The case dragged on for several years, during which time there were mass demonstrations not only in America but also across the world. When they were finally executed in 1927 Ridge and many other writers, artists, and intellectuals gathered in Boston to protest. Ridge wrote a long poem, published as a book called Firehead, which saw Christ as the “most famous victim of institutionalised murder,” and drew parallels with the case of Sacco and Vanzetti. Svoboda says that it was a “smashing success,” though some people did claim that they found it difficult to understand. And she takes the opportunity to relate it to work by other “obscure” (in the sense of not being immediately clear) poets of the period, in particular Hart Crane. Shortly after Firehead appeared Ridge decided that she wanted to visit Babylon. As Svoboda puts it: “Undaunted by lack of funds or unfamiliar ways, Lola Ridge set sail alone for Babylon on the Tuscania in mid- May, 1931.” She had been given some money for the trip by a wealthy patron, and she soon began to contact other friends and acquaintances to ask for more. Her estranged husband was one of those who helped her, though he was earning little as the Depression began to bite. And Ridge never made any bones about wanting to rid herself of him, even to the point where she encouraged him to find another woman. Svoboda comments that, “It was as if the Depression and its deprivations didn’t exist for her with regard to others.” The amazing thing was that, despite the harsh economic climate which affected most people, including those who might be thought of as still being comfortable, people did come through with gifts. They might only send fifty dollars when she asked for two hundred, but Ridge nearly always got something. Svoboda’s narrative of Ridge’s adventures as she passed through Corsica, Beirut, Baghdad, Paris, London and other places, somehow managing to often stay in comfortable hotels while claiming to be without funds, is illuminating. Ridge’s health appears to have suffered during her trip, at least if her own reports were true, though the thought occurred to me that illness may have been an effective way of eliciting sympathy, and money, from certain people. And it’s difficult to know what to make of a letter she wrote to David Lawson in which she told him that she was returning to America just for him. Depression at the thought of the son she’d abandoned affected Ridge’s health on her return to New York. She was still dependent on Gynergen, and in 1933 her condition was serious enough for her to be taken into hospital. Lawson was working, but pay cuts affected his earnings, and Ridge complained that he ought to get a better job so they’d have a higher income. This at the height of the Depression when any kind of job was welcome. And she could always find someone to let her convalesce with them while Lawson tried to hold on to any work he could get. The years 1934 and 1935 were quite good ones for Ridge from the point of view of earning money from her poetry. She won a Poets Guild Prize of five hundred dollars, shared a Shelley Award which brought in some additional cash, and was awarded a Guggenheim Grant. Her book, Dance of Fire, was published in 1935 to friendly reviews. Svoboda doesn’t seem to offer any evidence that Ridge did more than spend the money on herself. She headed for the Taos Art Colony in New Mexico, and then went to Santa Fe where she met a Mexican, Rafael Alfredo (or Alfonso; Ridge used both names when referring to him in letters) with whom she had an affair. She wrote to the long-suffering Lawson to send her various items of clothing, so she could keep up appearances, then told him, “you are a self-centred person who has besides a great deal too much to do for himself and I’m not blaming you for a combination of character and circumstances.” But, Svoboda acknowledges, she did blame him, “the devoted husband who had been sending her books and money and sleepwear and medication for at least the last ten years of her wanderings.” And she moved on to Mexico City and back to the United States, where she spent time in California, all the while asking for money from various people, and finally to New York. But she wasn’t getting any younger, and at some stage she had to move back in with Lawson so that he could take care of her. She continued to write poems, but didn’t publish them. And her body finally gave way and she died on the 19th May, 1941. Svoboda doesn’t attempt to make excuses for Ridge’s behaviour in terms of the way in which she frequently obtained money from patrons and friends. Or how she expected David Lawson to continue to support her, despite them not being together. But she does wonder if a male poet might be criticised for acting in the same manner? And plenty of them have, of course, and their actions have been ascribed to their being bohemians, and therefore free spirits. I recall not too long ago reviewing a biography of the English poet, David Gascoyne, and it quickly became apparent that he was always able to find a sympathetic woman to take care of him whenever he was impoverished or homeless. All that aside, it is proper to ask if Ridge’s poetry is worth reviving? Personally, from what I know of it, it is. Or at least much of it is. Towards the end of her literary career she wrote quite a few sonnets which I’ve never found of great interest. Her friend, the novelist and poet, Evelyn Scott (now a similarly forgotten figure), told Ridge that she thought it was a mistake to spend time on the sonnets and that it was her free verse she would be remembered for, if she was to be remembered. That’s certainly true, and it is “The Ghetto,” “Frank Little at Calvary,” “Stone Face,” (a poem about Tom Mooney, a falsely-imprisoned labour activist) and similar longer free-verse poems, together with some effective short pieces, which I consider will provide worthwhile reading. It may be that there is some documentary value in poems like those I’ve referred to in that they refer to social and political personalities and situations. Recent publications where Ridge is mentioned, such as Carey Nelson’s Revolutionary Memory: Recovering the Poetry of the American Left and Alan Filreis’s Counter- Revolution of the Word: The Conservative Attack on Modern Poetry, 1945-1960, might just give that impression to some readers. But there is more to Ridge’s work than its radical sympathies, important though those were to her. In John Timberman Newcomb’s How Did Poetry Survive? The Making of Modern American Verse there is a useful discussion of one of Ridge’s less overtly-political poems from Sun-Up. But elsewhere in his book he refers to her “fervent Christian Marxism,” a categorisation Terese Svoboda would surely disagree with. It’s interesting to note that while there are reprints of The Ghetto and Sun-Up, and second-hand editions of Firehead and Dance of Fire can be located, there aren’t any copies of Red Flag available outside libraries. Does the title still bother some people? The red flag is automatically associated with communism in many minds, but has a longer pedigree, and in any case Ridge was never a Party member. I sometimes wonder what happened to many books with similar titles, and books by left-wing writers in general, during the McCarthy years in America? Were they taken off the shelves of libraries and removed from private collections? And then were somehow “lost.” I remember reading a memoir by the novelist Albert Halper in which he told how, when he knew he was to be visited by FBI agents, he cleared his bookshelves of any “suspicious” titles, including even copies of Russian classics by Tolstoy, Turgenev, and others. Did people who bought copies of Lola Ridge’s Red Flag when it was first published later decide that it wasn’t a title they wanted on open display in their homes? Perhaps I’m exaggerating the situation? Terese Svoboda has written a fascinating account of the life and work of Lola Ridge. She has also set her firmly in context and in doing so provided an informative and lively story of a period of modernist American poetry and its social background. There are numerous references to magazines, their editors, and the writers published in their pages. And Svoboda doesn’t just mention them in passing, but often provides interesting information about their activities. The book has extensive notes and a good bibliography.

|