|

AN

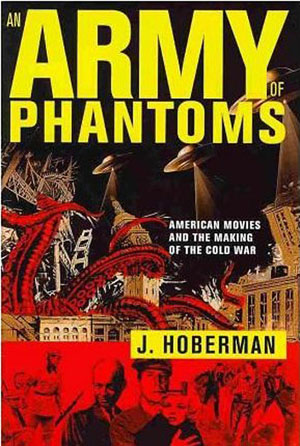

ARMY OF PHANTOMS: AMERICAN MOVIES AND THE MAKING OF THE COLD WAR by

J.Hoberman Reviewed by Jim Burns

Looking along my shelves I can see a whole section of books about Hollywood in the 1940s and 1950s when a large number of writers and others found themselves under fire because of their political interests and affiliations. Some were even accused of attempting to insert left-wing propaganda into the films they wrote or directed. Histories, memoirs, accounts of the making of specific films, interviews, and even a few novels focus on the activities of individuals and what happened to them after they came under suspicion, were sometimes forced to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee, and either became friendly witnesses and preserved their careers by naming colleagues they said were communists, or defied the Committee and were blacklisted. Even those who didn't appear but had the wrong friends or had shown too close an interest in alleged subversive ideas often found that they were on a kind of greylist and work began to dry up. It was a sad time in Hollywood and America generally, and it shouldn't be thought that it only affected people in the film capital. Numerous academics, civil servants, union activists, and others, lost their jobs and were harassed by the authorities. But it's the film community that occupies our attention here, and I think one of the first questions we need to ask is why Hollywood turned from the left/liberal mood of the 1940s, when pro-Soviet films like Song of Russia, Action in the North Atlantic, North Star, and Mission to Moscow could be made, to the right-wing paranoia of the 1950s and a spate of anti-communist films. The obvious answer is that after 1945 attitudes towards Russia and communism quickly changed. Thinking positively about both had only been a temporary measure and once the war was over old suspicions about Russian intentions soon re-surfaced. It's an illusion to imagine that the pro-Russian sentiments of the war years had been shared by everyone. I doubt that political realists expected the wartime comradeship to last, and once events began to show that Stalin had no intention of extending the spirit of co-existence attitudes rapidly changed. The threat from strong Communist Parties in Italy and France, communist takeovers in Czechoslovakia and Hungary, the Berlin Air Lift, Russian development of the atom bomb (helped by spies in the USA), and the start of the Korean War, which didn't directly involve Russia but could be seen as part of an overall strategy of communist domination, convinced many people that communism was the major threat to Western democracy. An Army of Phantoms primarily concerns the 1945-1960 period but in a fast-moving prologue Hoberman looks at events and films in the years between Pearl Harbour and VJ Day. And he recounts a telling little story about the filming of Back to Bataan, a wartime flagwaver that starred John Wayne, a noted rightwinger. Wayne, it seems, liked to taunt the scriptwriter Ben Barzman, a known communist, with comments about Stalin. Barzman told him that, after the war, "the Russians will be our friends," to which Wayne replied, They'll be your friends." It was, perhaps, a minor incident, but in its way it illustrates how, despite wartime co-operation, basic attitudes hadn't changed. Wayne was not alone in Hollywood in seeing anti-communism as a priority, and in the post-war era he would be active in making life difficult for left-wing writers and actors. It needs to be said that anti-communist sentiments were not the only reason why politics loomed large in the late-1940s. There were major disputes by unions representing craft workers which divided the community And the investigations into the political backgrounds of certain writers, directors, and actors, were almost an extension of what had taken place in the 1930s as writers fought to form a union (the Screen Writers Guild) and have it recognised by the various studios. The SWG was something of a battleground as right, moderate, and left-wing factions competed for control of it. There is probably sufficient evidence to show that the rancour that arose from the 1930s disputes continued after 1945 and was at least partly responsible for the way in which communists were hounded and blacklisted. I would guess that a lot of old scores were settled when various people identified others as communists or fellow-travellers. I don't want to extend these comments too far, but anyone interested might like to refer to Nancy Lynn Schwartz's The Hollywood Writers' Wars, published by Knopf, New York, 1982. By 1947 the tempo of what has been referred to as "witch-hunting" was increasing. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) arrived in Hollywood to begin its investigations into supposed infiltration of the film industry by communists. Known members of the Communist Party were still working openly on films. Crossfire, for example, was produced by Adrian Scott and directed by Edward Dymtryk, both communists, and its writer, John Paxton, was described as "friendly to the left." Scott was also involved with the filming of The Boy With Green Hair, written by Ben Barzman and Alfred Lewis Levitt and directed by Joseph Losey, all of them members of the Communist Party. Both films could be described as socially conscious in the way that they dealt with problems arising from prejudice. And films like Body and Soul and Force of Evil could be seen as questioning capitalist values and were written and/or-directed by Robert Rossen and Abraham Polonsky, two more members of the Hollywood communist community. But time was running out for them. HUAC called witnesses to testify about communist machinations in the film capital. The actor Adolphe Menjou claimed that Hollywood was "one of the main centres of communist activity in America," and Jack Warner, head of one of the major studios, trotted out a long list of people (mostly writers) he said were communists and announced that he'd already fired them. The chairman of HUAC asserted that what he'd heard had convinced him that the Screen Writers Guild was "under the complete domination of the Communist Party." There was still opposition to what was happening, and when nineteen so-called "unfriendly witnesses" were summoned to appear before HUAC in Washington the Hollywood liberal establishment mobilised and sent a deputation to support the nineteen. It included such luminaries as Humphrey Bogart, Danny Kaye, and Lucille Ball. In the event not all the nineteen were called, but a group who became known as The Hollywood Ten were defiant when questioned. They were eventually held to be in contempt and sent to prison. Realisation about what HUAC could do set in and the opposition to it began to crumble. The tactics employed by the Ten had alienated some people as they argued, shouted, tried to make speeches about democracy, and accused the Committee of fascism, totalitarianism, and abuse of free speech and the Constitution. Stars like Bogart were pressured to back away from appearing to support alleged communists, and studio bosses, if they hadn't already, began to apply their own forms of exclusion. It all tied in with the general mood in the country as fears of spies, atomic war, and communist conspiracies turned into near-paranoia. In 1948 John Ford started to film Fort Apache, the first of his cavalry trilogy. Hoberman says it "opened in New York on June 25th - one day after the Soviet blockade of Berlin created a beleaguered Western fort in the midst of hostile Red territory." He sees the film as having some liberal elements but adds that it "is a vision of total mobilisation with an appropriate emphasis on order and eternal vigilance; militarised suburbia. The bombing of civilian populations in World War 2 suggested that the next war might have no front - or, rather, that the front might be in America's living room." One thing that Hoberman is good at is showing how the communist press responded to films, and Ford's second instalment of his trilogy, She Wore A Yellow Ribbon, brought a review in The Daily Worker which questioned its view of the Indian Wars as "a glorious page in our history." The positive view of ex-Confederates serving in the cavalry was also questioned. By the time Ford completed the trilogy with Rio Grande, described by Hoberman as "a right-wing attack on the status quo," the Korean War was under way and the film's theme of soldiers frustrated because orders from Washington stop them crossing into Mexico to rescue children kidnapped by Indians matched the frustrations felt by American commanders in Korea when political concerns limited their actions. It was not long afterwards that General MacArthur wanted to bomb China when it sent its troops to support North Korea. HUAC returned to Hollywood in 1951 and this time the list of victims of its investigations lengthened as people hurried to name names and so save their own careers. Guilt by association was enough to get many writers and others blacklisted. At the same time the number of anti-communist films increased. The Red Danube, The Red Menace, Pickup on South Street, and I Married a Communist were just a few of them, and it was said of the latter film that Howard Hughes used it as a kind of loyalty test by asking certain directors to work on it. If they refused, as did Joseph Losey, Nicholas Ray, and John Cromwell, they were immediately suspect. What many of these films suggested was that communism was akin to crime and so communists were portrayed as behaving like gangsters and were not averse to murder if it helped further their aims. In Pickup on South Street, in fact, they're depicted as a breed below common criminals, one of whom when refusing to sell information to a communists, says: "Even in our crummy business you gotta draw the line somewhere." Hoberman's analysis of this film is fascinating and he neatly shows how the business ethic dominates the actions of many of its characters, communists and criminals. The police apart, little of the outside world intrudes on their lives as they fight for the best deal. Another film that Hoberman dissects is Panic in the Streets, directed by Elia Kazan who, after a period of doubts, testified before HUAC and offered names of communists, including people he'd worked with in the Group Theatre in New York in the 1930s. Panic in the Streets is a "trim little thriller," in the words of Kazan's biographer, Richard Schickel, and tells how a merchant seaman, unwittingly infected with pneumonic plague, is murdered on the docks in New Orleans. The authorities realise that he will have infected the people who killed him and set out to track them down. They also have to try to stop the news from spreading so that there won't be panic in the streets. It sounds straightforward enough, but Hoberman reads it as a possible parable about the contagion of communism. He quotes the Attorney General at the time as saying that communists "are everywhere - in factories, offices, butcher stores, on street corners, in private businesses. And each carries in himself the germ of death for society." Did Kazan have that in mind when he made the film? Perhaps of more relevance is did people watching Panic in the Streets draw a parallel, consciously or not, with the supposed communist threat? Kazan later directed On The Waterfront from a screenplay by Budd Schulberg, another ex-communist who had named names, and more or less made it into a justification for his own co-operation with HUAC. The hero, played by Marlon Brando, testifies before a committee investigating corruption in the waterfront unions, and is cold-shouldered by his fellow-workers who, despite their knowing who the gangsters are, see informing as a greater sin than trying to clean up the unions. But Brando finally wins the day when the workers eventually follow him rather than the corrupt union boss. Was Kazan suggesting that history would judge him right for informing? The early-1950s also produced a number of science-fiction films that may have helped fuel the paranoia of the period. The Thing, It Came From Outer Space, The Day The Earth Stood Still, Invasion of the Body Snatchers; did they all suggest that something alien was waiting to take over? When the hero of Body Snatchers is seen at the end uselessly shouting a warning to people obviously ignoring him was it a way of drawing attention to the conformity that would be enforced if communists took over, or was it a protest against the mass conformity that was evolving as a combination of growing consumerism and increasing governmental control worked against the interests of the individual? In the film, with its screenplay originally by Daniel Mainwaring, a one-time left-winger, and later re-worked by Richard Collins, an ex-communist who co-operated with the Committee, the hero notes how "people have allowed their humanity to drain away....only it happens slowly rather than all at once. They didn't seem to mind." John Wayne crops up a lot in this book, his right-wing beliefs being evident! He starred in Big Jim McLain as a tough, no-nonsense investigator sorting out communists in Hawaii. And he made his views on High Noon, in the cinemas around the same time, well-known. Wayne was outraged at the idea of the sheriff (played by Gary Cooper) almost having to beg for support when it's obvious that a gunman and his gang are coming. And the final scene where the sheriff, having killed the bad guys, throws his badge on the ground and leaves town with his wife, further upset Wayne. He seems to have blamed Carl Foreman, the screenwriter, for what Wayne thought was the un-American tone of the film, and he was quoted as saying that he had "helped run Foreman out of this country." Foreman moved to Britain where, among other things, he worked with Michael Wilson, another blacklisted writer, on the screenplay of The Bridge on the River Kwai. It's of interest to note that a number of patriotic British films, such as Zulu, Lawrence of Arabia,and Young Winston, had contributions from blacklisted Americans. But to return to High Noon, John Wayne may have been upset but the film was immensely popular, perhaps because it could be interpreted in a variety of ways. It functions as an orthodox western, of course, but Carl Foreman always maintained that people knew he was drawing a parallel with what was happening in Hollywood as HUAC (the bad guys) arrived and the locals were too frightened to back up the few who stood up to the Committee. The scene where someone does initially offer support but then withdraws it when he realises no-one else is coming forward had its basis in what actually happened to Foreman. Another interpretation of High Noon came from a Swedish film critic who said that it was "the most honest explanation of American foreign policy. The marshal (America) had wanted peace after cleaning up the town five years before (i.e.WW2) and reluctantly must buckle on his gun belt again in the face of new aggression (the Korean War), and eventually his pacifist wife (American isolationists) must see where her true duty lies and support him." I'm not sure how Carl Foreman would have viewed this analysis of his script, but it is a fact that High Noon was the film most requested for showing at the White House by a number of American presidents. Eisenhower was a great fan and Bill Clinton saw it as "a movie about courage in the face of fear and the guy doing what he thought was right in spite of the fact that it could cost him everything." As the 1950s developed and Senator McCarthy's power waned the number of films taking a crude anti-communist approach declined. Hollywood still reflected (exploited?) society's paranoias and films about juvenile delinquency began to attract attention. The Wild Ones, The Blackboard Jungle, and Rebel Without a Cause were probably the best-known ones. Intellectuals, however, may have been more concerned about Walt Disney's Davy Crockett: King of the Wild Frontier which opened in around one thousand cinemas across America. The popularity of the film and the TV series that followed it, the mass-marketing of Davy Crockett-related merchandise, the widespread broadcasting of the song about Crockett were all viewed with suspicion and dismay by contributors to highbrow publications. Communism may have implied one kind of conformity but so did mass culture. It wasn't long before Budd Schulberg began work on A Face in the Crowd, a screenplay adapted from his story, "Your Arkansas Traveller," which was about the rise to fame of a hillbilly singer who uses a populist approach and, helped by TV, becomes a national hero who, it is suggested, might run for president. Elia Kazan directed the film and, curiously, it was acclaimed by a critic in a communist publication, The People's World, who identified Schulberg and Kazan as "stool pigeon witnesses before the Un-American Committee," but added that they'd made "one of the finest progressive films we have seen in years." Perhaps they hadn't lost all their radical ideas, the critic said, or could it be that guilty consciences had "prompted them" to work on such a story? Hoberman comes to the conclusion that "Kazan and Schulberg intuited that, in the nation's dream life, media personalities and movie stars would now nominate themselves for the leading role." And he adds that, in the contest between "moribund, repressive Communism and responsive audience-pleasing television," it was TV that prevailed. Kazan and Schulberg "may have publicly repudiated their youthful politics, but the fear and loathing so forcefully expressed in A Face in the Crowd placed them again on the losing side of history." I count myself lucky because I grew up at a time when the cinema was dominant and I spent a large part of my young life watching most of the films that Hoberman discusses. Some of them still turn up on TV and others are available in Video or DVD format, though it's not quite the same as having seen them when they appeared. I have to say that I was often surprised by Hoberman's interpretations of their stories. I was, and still am, an admirer of John Ford's cavalry trilogy, but I can't claim that when I first saw them I thought of them as anything more than superior westerns. When I watch the films again I'll have Hoberman's observations to add to my own. At the same time, however, I'll wonder whether or not Hoberman's comments are necessarily valid. The subversive thought occurs to me that a critic can take any period and select a number of films (or books or plays) which seem to have relevance in terms of being possibly related, in one way or another, to events in the wider world. And perhaps it would be equally easy to select films or whatever that have no relevance at all. I don't want to close this review on a negative note by suggesting that Hoberman's views lack substance. That would be completely wrong. An Army of Phantoms is not just an illuminating analysis of a critical period in film history, it's also a thoroughly entertaining book. He has a lively way of writing and likes to lightly mock many of the directors, writers, producers and actors he mentions. Members of the Hollywood branch of the American Communist Party - the "Swimming pool Soviet," as they were sometimes called - are usually referred to as "Comrade Lawson," "Comrade Maltz," and so on. And the pretensions of both right and left are wittily held up for examination, as are the follies and foibles of the bosses. There's an anecdote about Elia Kazan and John Steinbeck showing the screenplay of Viva Zapata! to Eddie Mannix, the tough general manager at MGM. Mannix took them to task because of the way the film portrayed revolutionaries in a positive light, but on being told that the Mexican government had offered substantial financial support for the film his attitude changed. "What the hell," he said, "Jesus Christ was a revolutionary, too." When all was said and done it was money that decided most things in Hollywood.

|