|

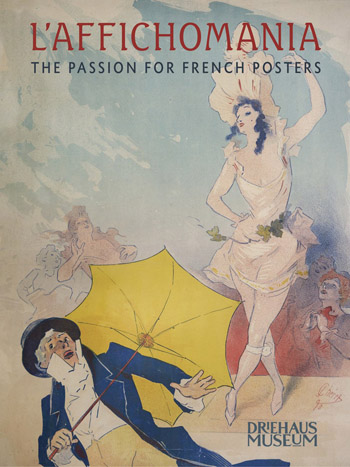

L’AFFICHOMANIA : THE PASSION FOR FRENCH POSTERS

By Jeannine Falino

Richard H. Driehaus

Museum

(distributed by The University of Chicago Press). 127 pages. $32.50.

ISBN 978-0-578-16802-9

Reviewed by Jim Burns

I recently saw an exhibition of Alphonse Mucha’s work at the

Walker Art

Gallery in Liverpool, England,

and admired his skill at combining commercial requirements with

artistic accomplishments. In their way, Mucha’s posters are possibly

the most representative in terms of being identified with Paris of a certain period in the minds of many

people. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec probably demands attention when it

comes to Montmartre and the

bohemian world of the Moulin Rouge and its performers, but Mucha

commanded the fashionable scene with his famous posters for Sarah

Bernhardt, and those concerned to advertise cigarettes, drinks, and

other commodities.

There were other producers of posters, and several of them are

alongside Mucha and Lautrec in this handsome book that accompanies

an exhibition at the Richard H. Driehaus Museum in

Chicago

(February 11,2017 to January 7, 2018). Driehaus, a

businessman and philanthropist, is an avid collector of posters and

has built up a fine collection which provides the basis for the

exhibition.

Jeannine Falino, its curator, says that the “Golden Age” of French

poster art was during the period from the 1880s through to the

late-1890s. There were some practical reasons for this. In 1881 a

law was passed which opened up the freedom of the Press, including

the unlimited production of posters, prints, etc. Around the same

time, Jules Chéret had made advances in the use of colour

lithography. The result was that “colour-printed posters were

exhibited in that most public of galleries – the street – where they

began to blur the boundaries between fine and popular art”. Someone

described them as “frescoes, if not of the poor, at least of the

crowd”.

It’s interesting to note that, almost from their first appearances,

the posters were collected. There had been posters before, of

course, but they were mostly in basic colours and simply stated the

appropriate information they were designed to disseminate. With

Chéret’s posters, and those of his contemporaries like Mucha, Eugène

Grasset, Theodore Steinlen, and Lautrec, the artistic value of them

was immediately recognised. There are stories of them being stripped

from the walls and hoardings almost as soon as they were posted

there. Special kiosks were built to display them. Dealers began to

sell posters, catalogues were printed, and there were exhibitions of

poster art.

There are a couple of illustrations which point to the profusion of

posters in the Paris

of the period in question. A painting by Jean Béraud simply entitled

The Kiosk shows a

smartly-dressed woman looking at posters on a kiosk while a well

turned-out man is likewise peering at them. The other painting,

Posters on a Wall and a Man

mending Metal Pots by Louis-Robert Carrier-Belleuse, has a

bourgeois couple inspecting posters on a wall, some of which are

peeling away. There may be some implied social commentary in this

painting. Not everyone welcomed the idea of posters being displayed

everywhere and they probably did become tattered and torn and

unsightly. It may also be correct to assert that showing the

working-class man busy at his job, while the couple have time to

indulge in checking on what the posters are advertising, indicates

that they were essentially there to sell things that the low-paid

couldn’t afford. But perhaps I’m reading too much into the painting?

Chéret has been described as the “king of the poster,” and the

writer J.K. Huysmans is said to have “preferred his originality and

energy to the stifling and unimaginative academic painting of the

state-sponsored Salon of the Society of French Artists”. He had been

trained as a lithographer and was skilled at the use of colour

techniques. As for influences, he referred back to painters such as

Watteau and Fragonard, with their “idealised qualities of pleasure,

leisure, and reverie”. The attractive and always-happy young women

portrayed on Chéret’s posters became popularly known as

chérettes. And he “strove

to integrate subject and text”, which according to Jeannine Falino,

“was an improvement on traditional poster design where text was not

visually connected to the image”.

Eugène Grasset, from the examples of his posters, was nowhere near

as flamboyant as Chéret, and appears to have been influenced by the

English arts and craft movement. His women are appealing, but seem

more-mature than Chéret’s, and there are no displays of bare

shoulders and plunging necklines. One poster, advertising bicycles,

offers only a hint of the actual machine and it’s the woman holding

the handlebar who essentially attracts attention. This might be seen

as using sex to sell a product, but it doesn’t really come across in

that way. She is too demure. The accompanying note refers to her as

“smartly dressed and self possessed”, and I was put in mind of the

contrast afforded by a poster, also

advertising bicycles, in the aforementioned Liverpool exhibition,

where the curves of the handlebar might have some relationship to

the curve of the cleavage seen because of the low-cut dress the

woman is wearing.

I have to admit to a personal prejudice in favour of

Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, perhaps because he loved cats, but

also because of his links to bohemian

Montmartre and its radical inclinations. The

Montmartre Museum in Paris has

examples of his work, and some years ago, visiting an exhibition in

Giverny, I made a short detour to

Vernon

to look at several paintings by American Impressionists, and to my

delight found that the gallery there was also showing a Steinlen

exhibition. He was clearly more politically aware than the others,

and had a “more compassionate realistic style”. There is a Steinlen

poster, La Rue, done to

advertise the work of a printer, which shows a cross-section of

Parisian society, ranging from workers to obviously-affluent

bourgeoisie. It isn’t overtly political, but the placing of the

different characters might indicate some sort of confrontational

situation, albeit not a violent one.

A more-direct social comment was made in Steinlen’s advertisement

for the novel, La Traite Des

Blanche (The White Slave Trade), which shows a self-satisfied

pimp with three prostitutes, one of whom has collapsed crying,

another who appears to be

howling in misery, and a third who might have accepted her fate.

This third figure had bare breasts in Steinlen’s original design,

but the censor intervened and the published version shows her

covered up.

One of Steinlen’s most-famous posters advertised

Le Chat Noir, the

“bohemian outpost for the avant-garde”. It’s suggested that he used

this illustration to also poke fun at Mucha’s “penchant for placing

haloes around the heads of his female subjects”, the large black cat

in Steinlen’s image having what appears to be one around its head.

Like Mucha and Grasset, he also helped publicise bicycles, and for

his poster introduced some humour, with the lady riding her machine

into a gaggle of startled geese.

The swirling long locks of hair so characteristic of many of Mucha’s

women, as seen on his posters, are what may persuade people to

almost-immediately identify his work, and relate it to their ideas

about Paris around 1900.

Described as “One of Mucha’s best-known images, the

Job poster is a beloved

symbol of art nouveau”. Job

was a brand of cigarette paper, and the inference was that smoking

was a “sensual experience”.

It’s interesting that the one woman in the book who actually

designed posters as opposed to being shown on them, was Jane Arché,

whose Hors Concours also

used a sophisticated woman to highlight the pleasures of smoking and

the quality of Job

cigarette papers.

In 1894, La Plume, a

Parisian literary magazine, started

The Salon des Cent, an

annual exhibition that continued until 1900 and was meant to show

the work of one hundred poster artists. Mucha did the poster for the

1897 exhibition, with a somewhat pensive-looking lady holding what

she is working on and peering at the viewer. The reference to the

number of artists producing posters give an indication of how

widespread their use was. Not all of the artists were necessarily

active all of the time in poster production. In a book I recently

found in a second-hand bookshop,

Paris 1900: The Art of the

Poster by Herman Schardt (Bracken Books, London, 1987), there

were examples of posters by Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis, and the

Spanish painter, Ramon Casas, but none of these artists went beyond

creating a handful of examples of the genre. Another bookshop-find

was Alain Weill’s large The

Art Nouveau Poster (Francis Lincoln Ltd., London, 2015), which

gives Paris a central place in its survey, but goes outside it to

take in Austria, Great Britain, the United States, and other

countries.

One of Henri Toulouse-Lautrec’s classic images is his striking

poster of Aristide Bruant, a singer of “realist songs,” who “gave

eloquent voice to the downtrodden who were living on the margins of

city life”. He hurled insults at the well-to-do people who slummed

it in Montmartre, and they, no

doubt, lapped it up, knowing full well that their lives and property

would be protected by the police, and the army, if necessary. It

wasn’t all that many years since the Commune had been savagely

repressed and thousands of working-class men and women shot.

But Lautrec specialised in posters which portrayed entertainers like

May Milton (an English performer with a limited range who quickly

disappeared from sight), La Goulue, and Jane Avril, a particular

favourite of his. There was an excellent exhibition,

Toulouse-Lautrec and Jane

Avril: Beyond the Moulin Rouge, at the Courtauld Gallery,

London,in 2011

There is an amusing

difference to be noted between Lautrec’s version of Yvette Guilbert

and the way she is shown on a poster by Chéret. In the latter she is

slender, graceful, and quite pretty, but Lautrec didn’t see her that

way. There is a story that she once said to him,” For the love of

heaven, don’t make me so appallingly ugly! Just a little less so!”.

Jane Avril was herself interested in posters for their own sake, and

not just because they advertised her performances. One of Lautrec’s

illustrations shows her at the printer’s shop, examining a poster,

while the man works at his machine in the background. Lautrec could,

of course, come up with a darker picture of life in Montmartre, when

he showed what life was like in the brothels he frequented, but

those illustrations were never likely to appear on public posters

around Paris.

Posters didn’t suddenly disappear after 1900 or so, but they began

to decline in importance as new technologies and popular interests

(the cinema was starting to attract attention) came into play,, and

the relevance and importance of posters began to diminish. Artists

moved on to different things. Mucha, always a Czech patriot, was

increasingly involved with producing work “aimed at elevating

awareness and admiration for Slavic culture”. Grasset devoted his

time to teaching. Chéret concentrated on murals. And Lautrec had

died.

L’Affichomania

is a beautifully-produced and fascinating book that works in its own

right to provide a picture of aspects of

Paris

during the Belle Époque. It isn’t the whole picture, of

course, and some might argue that the posters largely appealed

to the affluent or the bohemians, and that the working-class

population of Paris, certain individuals apart, probably took little

notice of them from an artistic point of view, and could only dream

about most of what they

publicised or promoted. I’m not sure about this, and it would be

useful to have some information about where the posters were placed.

Advertising of any kind is usually aimed at people who can afford to

purchase the products on offer.

These are questions for a social historian, and shouldn’t be allowed

to distract from an appreciation of the skills of the artists

concerned, and the sheer attractiveness of what they produced.

|