|

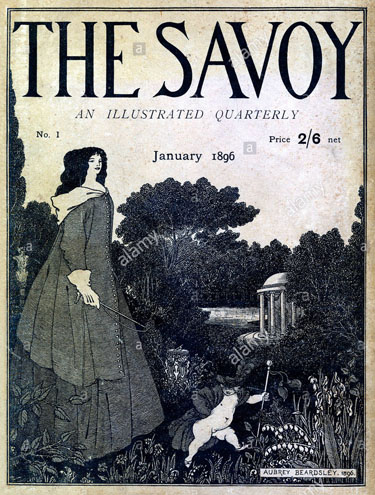

THE

JIM BURNS

The magazine most associated with the 1890s in

On the whole, the contents of

The Yellow Book were, Beardsley apart, innocuous enough. Poems,

short stories, articles, illustrations. I doubt that anyone, then or

now, would be likely to take offence at what was on show, unless it

was because the general impression given did not fit into the

framework of hearty writing which promoted healthy living, sporting

prowess, patriotic sentiments, and a mistrust of foreign influences.

According to some commentators, too many of the contributors to

The Yellow Book displayed

a disturbing interest in what was published and painted in

It may not have seemed a propitious time for someone to launch a new

magazine which would feature Beardsley and certain writers, such as

Arthur Symons, Ernest Dowson, Lionel Johnson, and John Gray, who

were often linked to writing looked on as having the flavour of

decadence. However, behind

The Savoy, the title of the projected publication, stood Leonard

Smithers, a man who had trained as a solicitor, worked as a dealer

in rare and second-hand books, and was known to publish and sell

work that others viewed as pornography. It wasn’t all he published,

and it has been said of him that, with the “dramatic backlash which

followed the tragic fall of Wilde”, had it not been for Smithers,

“the young avant-garde and artists of the

fin de sičcle” would have

lacked any sort of financial and other support for their work.

The Savoy was one way of

helping them, though I’m sure Smithers wasn’t against making money

while he was at it.

Smithers invited Arthur Symons to edit

The

The first issue came out in January, 1896. If it was designed to

attract attention it may have done so by the inclusion of three

chapters from Aubrey Beardsley’s novel,

Under the Hill, with

illustrations by the author. There have been various editions of

this uncompleted work, and the sections published in

The Savoy were

expurgated. Arthur Symons did not have a favourable view of

Beardsley’s literary work, and his opinion of the artist’s attempt

at a novel was that it was “hardly more than a piece of nonsense”.

But he was over-ruled by Smithers.

It’s perhaps worth noting that an unexpurgated version of

Under the Hill was

published by Leonard Smithers in a limited edition in 1907. Smithers

rarely missed an opportunity to capitalise on Beardsley’s

reputation, and was quite happy selling forgeries of his drawings.

He had met an “impecunious barrister” in a pub one night, and

discovered that the man had a talent for producing Beardsley-like

illustrations, and between the two of them they built up a steady

business for supposed Beardsley originals which collectors soon

snapped up.

Beardsley apart, the issue opened with a long essay by George

Bernard Shaw on the subject of “Going to Church”, which it seems

The Times said was the

best contribution, and which Stanley Weintraub, commenting much

later, considered Shaw’s “most personal statement of his feelings

about religion, and his best-shaped essay, foreshadowing ideas he

would later put into his plays”. Was the inclusion of Shaw writing

about religion designed to give the magazine an air of

respectability? It’s impossible to know for sure, but in any case

Shaw’s views were not usually aired to please the public.

Arthur Symons was never reluctant to print his own work in

The Savoy, and in the

initial issue he had a translation of a poem by Verlaine, one of his

own poems, and a long article about

Names that are still remembered stand out from the contents page:

Yeats, Ernest Dowson, Max Beerbohm, Havelock Ellis writing about

Zola. But who were Rudolf Dircks, Frederick Wedmore, Selwyn Image

and Humphrey James? A

quick reference to the Internet turns up information on Dircks

(translator of Schopenhauer and author of a book on Rodin, among

other things) and Image, who was an artist, designer, and poet, and

was associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement. Wedmore, “art

critic and man of letters”, published a lot in his lifetime, and his

books can be tracked down through reprint services and second-hand

book dealers. James is more elusive, though I admittedly only

carried out a brief search. The point is, I think, that none of

those I referred are the sort of people likely to earn a nod of

recognition now, apart from possibly a few academics and

specialists. I’m somehow put in mind of George Gissing’s

New Grub Street, and its

cast of literary characters toiling away in the “valley of the

shadow of books”, i.e. the British Library Reading Room. And mostly

fated to be forgotten.

Beardsley wasn’t the only artist in the first issue, and Charles

Conder and Will Rothenstein both made appearances, though neither

got along well with Smithers. Rothenstein took him to court in a

dispute over some work he had been commissioned to produce, and

which he claimed he’d never been paid for. He also disliked the

publisher as a person, and was later to assert that it was Smithers

who had led Beardsley into bad ways and persuaded him to turn to

pornography. As for Conder, it was said that he didn’t want to be

seen with Smithers because of the latter’s reputation, but he must

have known and caroused with him in

The first two issues of The

Savoy were successful from a financial point of view. The

magazine was still a quarterly, and the second issue had more

Beardsley, Dowson, Yeats, Havelock Ellis on Nietzsche, and Symons

with a translation of Verlaine, and a short story, “Pages from the

Life of Lucy Newcome”. The inspiration for it came from an encounter

with a prostitute, Muriel Broadbent, who Selwyn Image first met at

the Alhambra Theatre. Symons then took up with her, and it’s said

that they were “friends and occasional lovers for several years.”

Symons not only celebrated her in short stories, but also wrote a

poem about her, “To Muriel: At the Opera”.

Once again, some of the minor contributors arouse interest. Vincent

O’Sullivan was an American who chose to live mostly in

Leila MacDonald was a young Scottish poet and if she has any reason

to be recalled it may be because of her marriage to the ill-fated

writer, Hubert Crackanthorpe, who had a story in the third issue.

They eventually separated, took up with different partners, and the

four lived together for a time in

There was a poem by John Gray in the second issue of

The

The success of the first two issues persuaded Smithers and Symons

that The Savoy should go

monthly starting with the July, 1896 issue. It may have been a

mistake. Was there likely to be enough good material available to

fill the pages of a monthly publication?

George Moore had promised his new novel,

Evelyn Innes, for serial

publication in The Savoy,

but failed to come through with the requisite material. Stanley

Weintraub suggests that it was probably a hasty commitment and

Moore, who had achieved some success with

Esther Waters, later had

doubts about publishing his new book in a journal linked to a

notorious character like Leonard Smithers. Other writers may have

had similar concerns. And would sales continue to grow sufficiently

to cover production costs and payments to contributors? Smithers’

finances were never secure.

Another problem cropped up when the bookseller, W.H. Smith, refused

to stock the third issue, citing the use of a William Blake

illustration as likely to cause offence. On top of this problem,

which obviously badly affected distribution of

The Savoy, there was a

less than enthusiastic response from reviewers of the new issue. It

was particularly noticed that Beardsley was largely absent, as he

was from the fourth. Symons continued to contribute his own work,

and regulars like Dowson and Yeats were featured in both issues. One

or two newcomers were present, in, in particular Ford Madox Hueffer

(later to become Ford Madox Ford when the onset of the First World

War brought suspicion on anyone with a German sounding name) and

Lionel Johnson, a poet who died young. He had a stroke, probably as

a result of his heavy drinking. His “Three Sonnets” revolved around

visions of religion as found in the life of Mother Ann, founder of

the Shakers, the leaders of the Anabaptists in Munster in 1534, and

Hawker of Morwenstow, a Cornish Anglican priest and noted eccentric

– he excommunicated his cat for mousing on Sundays.

It was probably inevitable that

The Savoy would start to

show signs of its imminent demise, and it may be that a lack of

variety in the contributors had something to do with it. Symons had

three items in both issues five and six, and there were

contributions by his old standbys, Ernest Dowson and W.B. Yeats. It

wasn’t that their work was bad, but it could be argued that one of

the purposes of a magazine ought to be to publish fresh writing by

new writers. True, there were appearances by one or two newcomers.

Bliss Carman, a Canadian poet, resident in

By November, 1896, the writing was on the wall for

The Savoy, and it was

announced that the December issue would be the final one. The

seventh issue once more featured Dowson, Symons (an essay about

Verlaine), Yeats and Havelock Ellis. Again, it wasn’t that their

contributions lacked quality, but rather that the reader looking for

something different may have been disappointed at the scarcity of

new names. A story by Fiona Macleod (actually a pseudonym used by

William Sharp), and an essay by Osman Edwards on Emile Verhaeren,

the Belgian Symbolist poet, were hardly sufficient to convince

anyone that the magazine offered exciting new work. Symons’ own

interest in Symbolism was well known, and a few years later he

published a book called The

Symbolist Movement in Literature.

When the final issue appeared in December it was completely devoted

to work by Arthur Symons. A poem, a short story, two essays, a

translation of a Mallarme poem, and an epilogue entitled “A Literary

Causerie” which suggested that there was to be a twice-yearly

publication, “larger in size, better produced, and they will cost

more. In this way we shall be able to appeal to that limited public

which cares for the things we care for; which cares for art, really

for art’s sake”. Did the use of Symons’ own work, and that of Aubrey

Beardsley, who was the sole contributor of illustrations in the

final issue, indicate that there were no funds to pay other writers

and artists? Or perhaps they had just stopped submitting work when

it was known that the magazine was closing down? Beardsley’s work

was not new. He was desperately ill with tuberculosis in 1896 and

died the following year.

The plan for a bi-annual publication never came to anything. Money,

or the lack of it, no doubt played a large part in the failure to

get it off the ground. And it was a fact that the audience Symons

envisaged, one with an interest in art for art’s sake, was limited.

That had been demonstrated by the limited sales of

The

So many of the writers and artists who appeared in

The Savoy met early

deaths. Beardsley, Ernest Dowson, Lionel Johnson, Hubert

Crackanthorpe. They were what Yeats referred to as “The Tragic

Generation”. Arthur

Symons did survive, and lived until 1945, though there were periods

when he suffered from mental problems, and his literary career had

begun to peter out from the mid-1920s. As for Leonard Smithers, he

died in

There have been various accounts of Smithers death, but it does seem

accurate to say that his son’s description has been accepted as

true. Smithers’ body lay on a bed in a downstairs room, in which

there were two empty hampers. Other than that, the house was

completely empty of any kind of furniture. The death certificate

stated that death was due to “Cirrhosis of liver. 3 months -

Gastritis and Haematemesis & Exhaustion 2 days”. It would

seem that Lord Alfred Douglas, notorious for his role in Oscar

Wilde’s downfall, paid for Smithers to be buried in an unmarked

grave in

Eight issues of a periodical perhaps don’t amount to a major

statement, and yet The Savoy

has a place in literary history because of when it was

published, and the status of many of its contributors. It throws

light on a period when there was something of a struggle to

establish new ways of writing. It also highlights Aubrey Beardsley’s

place in British art, and draws attention to Arthur Symons, who did

a lot to sponsor and promote new writing. As for Leonard Smithers,

he deserves to be remembered as someone who liked good art and

literature along with his interest in pornography.

Selected Bibliography

This just lists the books consulted when writing about

The

The

Publisher to the Decadents: Leonard Smithers in the Careers of

Beardsley, Wilde, Dowson.

By James G. Nelson.

Arthur Symons: A Life.

By Karl Beckson.

Arthur Symons: Spiritual Adventures.

Edited by Nicholas Freeman. Modern Humanities Research Association,

Arthur Symons: Selected Early Poems.

Edited by Jane Desmarais and Chris Baldick. Modern Humanities

Research Association,

The Symbolist Movement in Literature.

By Arthur Symons.

Arthur Symons: Selected

Writings. Edited by Roger

Houldsworth. Carcanet Press, Cheadle Hulme, 1974.

Under the Hill.

By Aubrey Beardsley (completed by John Glassco). New English

Library,

Poetry of the Nineties.

Edited with an introduction by R.K.R. Thornton. Penguin Books,

Harmandsworth, 1970.

Writing of the Nineties.

Edited by Derek Stanford. Dent,

A Study in Yellow: The Yellow Book and its Contributors.

By Katherine Lyon Mix. Constable,

The Eighteen-Nineties: A Period Anthology in Prose and Verse.

Edited by Martin Secker. The Richards Press,

Sickert in

|