|

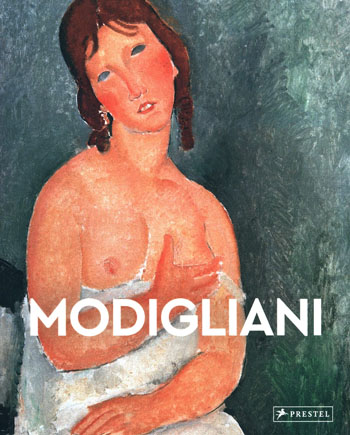

MODIGLIANI

By Olaf Mextorf

Prestel. 110 pages. £9.99. ISBN 978-3-7913-8659-1

Reviewed by Jim Burns

Olaf Mextorf’s introduction to this book quickly establishes a

picture of a man who, whatever else he did, became a model for the

notion of the doomed artist: “He was handsome, reckless and

dangerously ill”. He drank and drugged to excess, “women found him

irresistible”, and he was talented.

He might well have gone down as one more bohemian character

who cut a path through artistic

Paris in the early years of the twentieth century and was then

largely forgotten, but for one thing. The “talent” which, in the

form of his paintings, assured him of immortality. He wasn’t just a

proficient artist with an assured touch when it came to applying

colour to canvas. Modigliani created something new and original and

left behind paintings which are recognisable as only his.

Born in 1886 in Italy, Modigliani was rarely free from illness as a

child, a factor which, when added to the tuberculosis he later

suffered from, probably shaped his desire to live life to the full

while he could. He was known to admire the writings of Verlaine and

Rimbaud, and even when an art student frequented brothels and

regularly used alcohol and cannabis. He identified with the role of

the artist “on the edge of society”. It was inevitable that he would

soon move to Paris, which he did in 1906. The city was then the

centre of the art world and teeming with painters and sculptors from

many countries. And it was the focus for new ideas. Impressionism

had changed attitudes in many ways, and other movements soon

followed – post-impressionism, symbolism fauvism, cubism.

Modigliani became friendly with the German artist, Ludwig Meidner,

and with Maurice Utrillo who shared his liking for a lifestyle often

revolving around drink. But he was painting, and in 1907 exhibited

at the Paris Salon d’Automne, and in 1908 at the Salon des

Indépendants, both of which highlighted the works of the current

avant-garde. I think it’s true to say that Modigliani was still

formulating his own style at this time. His 1907 painting, “Jewish

Woman”, puts me in mind of works by Picasso from his Blue period.

Mextorf says that he “mixed with Jewish artists in Paris, where he

may have met the young woman who posed as a model for him”.

Montmartre, where Modigliani initially lived when he arrived in

Paris, was being replaced by Montparnasse as the area where artists

and writers congregated, and he moved there in 1909. He had met the

painter Chaim Soutine, who became one of his drinking companions,

and the sculptor Brancusi. I think we now tend to primarily look at

Modigliani the painter, but he did produce many sculptures, some of

them showing how he was influenced by non-European cultures. It’s

said that he had been friendly with Italian construction workers in

Paris, and that they loaned him tools for sculpting and provided the

materials from which he chiselled his heads

An early item that particularly caught my attention is a drawing

from 1911 of the Russian poet, Anna Akhmatova. Its simplicity is

striking, being little more than a “few thinly spaced lines” and a

small head. Mextorf

suggests that there is some affinity in this work with that of the

“British illustrator and graphic artist, Aubrey Beardsley”. The

deftness with which Modigliani creates a personality with seemingly

little effort certainly does have some resemblance to Beardsley’s

work.

Modigliani lived in poverty in Paris, and it was during this period

that he met the British painter, Nina Hamnett, whose portrait he

painted in 1914. It shows an attractive woman and is certainly a

world away from photographs of the Hamnett who is mostly remembered

as an alcoholic habitué of the Soho watering holes of the 1930s and

1940s. Hamnett, in turn, introduced him to the writer Beatrice

Hastings, with who Modigliani had a “tempestuous affair”. Her early

impression of him hadn’t been favourable, but she soon declared

herself “completely crazy about the pale, brutal bastard”. His

portrait of Hastings is curious and has a “secretive, somewhat

melancholic aura…….In parts of the canvas, an almost brittle

application of colour makes the picture appear like a slowly fading

memory”. Was Hastings fading from Modigliani’s life when he painted

her picture?

Modigliani may now be noted for his paintings of nudes, but when

they were first exhibited in Paris they attracted the attention of

the police and had to be withdrawn from public display. A lot of the

fuss seems to have centred around the pubic hair that all the models

clearly have. It was a convention that nudes usually had that part

of their bodies either hidden or clean-shaven. Did Modigliani

deliberately seek to cause a scandal by showing the pubic hair? He

certainly liked to shock the bourgeoisie with his behaviour, and it

may be that he would have been aware that the sight of the tufts

would invite a reaction.

It might be worth adding at this point that it was often assumed

that Modigliani usually had “more than just an artistic interest in

his models”. And it does seem true that what he captured on canvas

wasn’t only a matter of form in terms of curves and colour. There

does appear to be a suggestion of sexuality in the way the models

are posed. Look at the 1918 “Young Woman in a Shirt”, of which

Mextorf says: “The painting’s transience corresponds to the fragile

moment of intimacy that Modigliani is aiming to express. It is

uncertain which role the painter himself played in this context”. He

also discusses the 1917 “Reclining Nude”, and says that Modigliani’s

approach to the subject can be seen as “reducing nudity to sex”. Are

his models “objects of degraded male fantasies?”. He adds: “opinions

oscillate between transcendence and a suspicion of pornography”.

It’s Modigliani’s portraits that seem to me to me to hold more

interest, skilled and provocative as the nudes may be. As a

prominent member of the Montparnasse artistic community he

frequently painted his friends and associates. Early portraits such

as those of Paul Alexandre (an enthusiastic patron and collector of

Modigliani’s work) and Baroness Marguerite de Hasse de Villers (a

socialite with an occasionally difficult character) are both

accomplished, though the Baroness rejected her portrait. His

portrait of the Mexican artist, Diego Rivera, “deviates from his

otherwise typical stylisation”, and a portrait of Picasso is

described as “curious” and “characterised by a sketchy and fleeting

application of colour”.

The Polish art dealer Léopold Zborovski

had been introduced to Modigliani by the artist Moise

Kisling, and he and his wife helped to look after him in his final

years. Modigliani painted portraits of both Leo and Anna Zborovski.

With Leo, he captured a man with a quizzical expression on his face.

Is he weighing up the artist or the world in general? When it came

to Anna, known as a woman who was “cultivated, self-controlled and

reserved,” he saw her as “at peace with herself and unapproachably

beautiful”. Mextorf says that, although she disapproved of

Modigliani’s lifestyle, she “repeatedly posed as a model for him”.

She was presumably someone in whom his interest didn’t get to extend

beyond the artistic.

Others painted by Modigliani included Soutine and the portrait has

“restless brushwork that appears to echo Soutine’s personality,

described as unrefined”. When he produced a portrait of the Russian

sculptor Jacques Lipschitz and his wife Berthe, he charged “only ten

francs and some alcohol”. With the poet, critic and painter Max

Jacob – “Jewish, a homosexual and a drug addict” -

he saw someone whose “true feelings…..seem to be hidden from

view by an inner barrier”. There

was also an expressive drawing of the Swiss poet and novelist Blaise

Cendrars, author of, among other things, the wonderful long poem,

“Easter in New York”. Cendrars had joined the French Foreign Legion

in 1914 and had lost an arm in 1915. Like his drawing of Anna

Akhmatova, Modigliani’s few lines pack in a great deal in terms of

capturing something of Cendrars’ presence in the world.

Modigliani’s final years are probably those that many people may

know about, the nature of his death and its consequences having been

chronicled in various novels, films, biographies, and articles. He

had never been without a female companion in his life, and in 1917

met Jeanne Hébuterne, a nineteen year old art student, “a beautiful

young woman with blue eyes and thick, reddish brown hair”.

There was an immediate attraction between them and it was not

long before she had moved in with the thirty-two year old artist. He

was achieving some success, but was still “entirely destitute”. To

complicate matters even further her parents – staunch middle-class

Catholics – disapproved of her relationship with the older Jewish

bohemian painter.

There are two portraits of Jeanne in the book.

One, a head-and-shoulders, brings out something of her

fragile beauty, while the other, painted in 1919, shows her when she

was carrying their second child. Life with Modigliani had never been

easy for Jeanne. She was sometimes described as “quiet, weak and

willing to make sacrifices”, presumably to hold on to his

affections. He had continued to indulge in drink and drugs and to

associate with other women. There must have been some inner depth in

her character which enabled her to tolerate the unfaithfulness,

poverty, and even the verbal and physical abuse Modigliani directed

against her.

Things came to a head in January 1920. Modigliani had “caught a

severe chill while waiting for friends in the rain”. He was taken to

his studio where Zborovski and his wife looked after him. Jeanne was

heavily pregnant and unable to help. But when on the 22nd January

the Chilean artist Ortiz de Zárate, who lived below Modigliani,

returned from travelling he found the painter “unconscious in the

ice-cold studio”. He sent for a doctor who immediately had

Modigliani taken to hospital. He died there on the 24th

January 1920 without regaining consciousness. His death was ascribed

to “meningitis, which had been brought on by a tuberculosis

pathogen”.

It was left to Moise Kisling and André Salmon to raise funds to

provide for a suitable funeral and on the 27th

January

the funeral procession made its way from Montparnasse to Père

Lachaise cemetery. “Numerous artist friends, models, dealers and art

lovers followed Modigliani’s coffin across the city”. The day after

the funeral Jeanne jumped from a balcony at her parents’ home,

killing herself and her unborn child. Her family had disinherited

her when she went to live with Modigliani, and even in death they

refused to let her be buried near him. She was also denied

internment in the family vault because she had committed suicide.

As usual with bohemian tragedies there is the ironic fact that the

paintings and other works that Modigliani was paid very little for

soon began to accumulate in value. Death is a great stimulator for

raising prices in the art world. It’s also a fact that it has always

been difficult to ascertain how many works of art Modigliani created

and what happened to some of them. Drawings he did while sitting

in a café with friends were often given away or left on the

table. They may not have been major works, but would be sought after

now. As a consequence,

any number of forgeries may be floating around. His style was so

distinctive that it became relatively easy to copy.

It’s difficult to separate Modigliani’s work from his personal

legend. The paintings were an integral part of his life, often

chronicling through portraiture the friends and fellow-artists he

moved among. They provide a picture of the Parisian bohemia of the

first two decades of the twentieth century. Olaf Mextorf has managed

to evoke not only Modigliani’s life and work in this excellent small

book, but has also drawn attention to a lost world of artists and

others who, even while the First World War raged just a few miles

away, were attempting to preserve ideals of creativity and beauty.

|