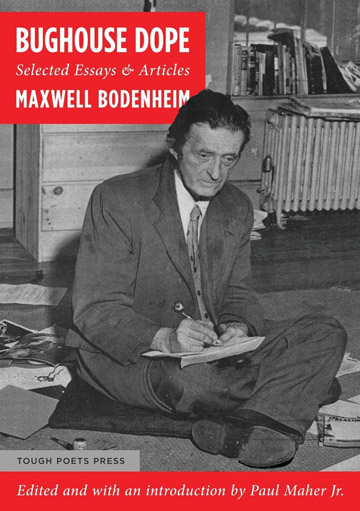

BUGHOUSE DOPE : SELECTED ESSAYS

AND ARTICLES

By Maxwell Bodenheim (Edited

and with an introduction by Paul Maher Jr.)

Tough Poets Press. 421 pages. $24.99. ISBN 979-8-218-37191-3

Reviewed by Jim Burns

It’s difficult to think of Maxwell Bodenheim without stories of his status

as a legendary figure of American bohemia coming to mind. Histories of

Greenwich Village recount the usual tales of sexual indiscretions and other

escapades, and his later decline into a drink-soaked shambles of a man

peddling his poems in the bars and

on the streets. Memoirs mention him, and he crops up in fictional

form in a novel like Terence Ford’s

He Feeds the Birds, published by the Dial Press in 1950.

The portrait painted isn’t a

positive one, with the poet sitting on a bench in Washington Square and

wondering who he can approach for “a quarter, a dime, a nickel, or even an

unused cigarette”.

What these accounts fail to mention is that Bodenheim (born 1892) had, in

his day, been a productive writer. Between 1923 and 1934 he published at

least twelve novels, and between 1920 and 1942, eight collections of poetry.

These are my quick calculations, and some sources suggest thirteen novels

and ten books of poetry. In addition, he had poems published in many

magazines, including The Dial, The

Little Review, Poetry, The Double Dealer, Tambour and

New Masses. I’ve just pulled a few names from Frederick J. Hoffman’s

The Little Magazine: A History and a

Bibliography (Princeton

University Press, 1946), and they show Bodenheim in the company of

contemporaries such as Hart Crane, Vachel Lindsay, Marianne Moore, Carl

Sandburg, Charles Henri Ford, and Parker Tyler.

It’s worth noting that he was

represented in the fourth edition of Louis Untermeyer’s

Modern American Poetry

(Jonathan

Cape, 1932).

Bodenheim also wrote a substantial number of essays and articles, and it’s

good to have them rescued from the publications they appeared in and brought

together by Paul Maher in Bughouse

Dope. As he says in his introduction, “I wanted Maxwell Bodenheim’s

written output to be free of the tabloid scandals that served to drag down

his literary legacy. My aim was to bring this sadly neglected writer back to

the literary marketplace”.

From a personal point of view, I welcome what Maher has done. Although I

know about the Bodenheim of the “tabloid scandals” and bohemian capers,

I have, in my slow way, tried to

collect a few of his books with a view to establishing an idea of his

qualities as a writer. I have seven of the novels and a couple of the poetry

collections. There is also the anthology,

Seven Poets in Search of an Answer

(Bernard Ackerman, 1944), with Bodenheim placed firmly alongside six other

socially-conscious poets like Norman Rosten, Joy Davidman, Alfred Kreymborg,

Martha Millet, and Langston Hughes, and indicating that he was still capable

of producing well-written poems. He wasn’t in good condition in 1944,

however, and Aaron Kramer, a fellow poet and contributor to the anthology,

who was one of the few who, over the years, maintained an awareness of

Bodenheim, remembered him arriving at the book launch scruffily dressed and

clearly intoxicated. (Aaron Kramer,

The Burning Bush : Poems and Other Writings 1940-1980, Cornwall Books,

1983). Kramer’s memoir of his encounters with Bodenheim is a moving tribute

from someone who loved his poetry and understood his failings in life and

literature.

There were others who knew about Bodenheim’s better days. Some years ago I

was in touch with the American writer Djelloul Marbrook. He’d written to me

about an article concerning Bodenheim I’d written for a little magazine in

England that had somehow found its way onto the Internet. He said he’d met

him when his aunt, the artist Irene Rice Pereira, sent him with some money

for the poet. She’d had a brief relationship with Bodenheim around 1926,

according to her biographer Karen A. Bearor in her

Irene Rice Pereira ; Her Paintings

and Philosophy (University of Texas Press, 1993). Pereira presumably had

sufficient good memories of the poet to help him along in, as far I can work

out, the late-1940s or early-1950s.

Jack B. Moore in his book, Maxwell

Bodenheim (Twayne Publishers, 1970) describes his work in

Seven Poets in Search of an Answer

as “generally competent, and less rhetorically flamboyant than his earlier

poems”. Faint praise, perhaps, but on the whole accurate.

He could be variable in both intent and achievement, but to his

credit there were usually lines in a Bodenheim poem that had something to

offer in terms of imagery and rhythm.

With regard to Bodenheim’s reviews and essays, they mostly cover a period

between 1914 and 1939, though there seems to have been a slackening in his

output in the Thirties. There may have been several reasons for this. His

personal situation was unsettled and there were signs of a drift into the

alcoholism and other problems that scarred his later days. And there was the

fact that, as more than one person who knew him pointed out, he had a

capacity for self-destruction. This didn’t only take the form of excessive

drinking and outrageous behaviour but also involved antagonising people who

might have been able to help him when it came to publishing. Bodenheim was

not given to flattering those in positions of power as editors and

publishers. It may sound like a piece of self-promotion, but he told his

wife, Minna, “I am a distinguished outcast in American letters – a renegade

and recalcitrant, hated and feared by all cliques and snoring phantom

celebrities, from ultra-radical to ultra-conservative”.

In a brisk 1916 review of The

Catholic Anthology, 1914-1915, published in the magazine

Others, Bodenheim came up with

some quick-fire comments on several of the contributors. A long poem by

Harriet Monroe taking up eight pages should have been “squeezed to thirty or

forty lines”, and “As an appreciator of poetry she is a giant, but as a

poet, she is too far behind the van”. Harold Monro “is always a bit

uncertain of himself, his unsubtle emotions brush over you, and have no

impress”. Alfred Kreymborg’s is said to have “a small unfortunate

representation”, and a poem by William Carlos Wiliams has a “solemn, tired

flavour”. As for Ezra Pound, he “has a group two miles below his best, and

six above his worst”, and John Rodker “enters a little blind alley of

rhythmical sound and diluted intricate emotions”. It’s smart stuff from a

bright young man just starting out, but it doesn’t aim to flatter editors

like Monroe and Monro, nor someone with influence like Pound. Bodenheim was

much more insightful about Pound’s work in a long review he wrote for

The Dial in 1922. On the subject

of “The Cantos”, he was of the opinion that they “represent the nervous

attempt of a poet to probe and mould the residue left by the books and tales

that he has absorbed, and to alter it to an independent creative effect”.

Bodenheim didn’t only write about poetry, and in fact the majority of pieces

in the book deal with different subjects. ForThe

Nation in 1922

he discussed “Psychoanalysis and

American Fiction”, and knew how to open with a phrase sure to attract

attention: “Psychoanalysis is the spoiled child of a realistic age, and its

boisterous manner should be corrected by a metaphysical spanking”.

The reader might have to pause to

consider if what Bodenheim said was valid, but would most likely be sure to

carry on reading to find out.

He could be amusing, too, as in “Soulful Flirtation Between ‘Beauty and the

Beast’ “, written for the Chicago

Literary Times in 1923. Bodenheim at one point ponders “ the recent

descent of professional ‘highbrow’ writers on vulgarity and the whistling

shimmy of street emotions.

Every now and then your “high brow” suspects he is not a regular guy, that

he is not in tune with the warm and profane undulations of the world. This

discovery brings him a nervous chagrin, and with a determined frown he

proceeds to invade the vaudeville theatre, the moving picture, the prize

fight and the evening problems of chorus girls”.

It may seem a little dated today. especially in its references, but

could still have a grain of truth in it when we consider the nonsense some

intellectuals have written in recent years to justify their interest in

forms of popular entertainment.

The Chicago Literary Times was a

publication established in Chicago by Ben Hecht, with Bodenheim as associate

editor. It would appear that the pair wrote most of its material during its

lifespan from March 1923 to June 1924. And the evidence for this is in

Bughouse Dope where Bodenheim’s

contributions account for over two-thirds of the total contents. Most of the

pieces are fairly short and their subject-matter ranges from the anarchist

Emma Goldman to D.H.Lawrence, Greenwich Village characters, T.S. Eliot, the

streets of New York, and much more. The object was to entertain as well as

inform, and Bodenheim was good at it. His

style was easy-going, conversational, and sometimes provocative in a

humorous way.

There was a decline in his output in the 1930s, though a lengthy essay,

“Esthetics, Criticism and Life” appeared in 1931 in

The New Review, a magazine edited

from Paris by Samuel Putnam. Maher says it was the first chapter

of a book “Bodenheim planned or indeed finished”, though only this

portion has survived. But by the early-Thirties he had begun to identify

with the left-wing in politics, as was reflected

in a couple of his novels,

Run, Sheep, Run (1932) and

Slow Vision (1934), and in poems

and articles he published in The

Daily Worker and New Masses.

Maher is of the opinion that a 1935 article in

The Daily Worker, “Yellow Hearst

in Frenzy of Anti-Communist Hysteria” may

have “doomed Bodenheim’s writing career for good in the mid-1930s”.

It was certainly a scathing view of William Randolph Hearst and placed him

in the same league with Hitler. But I suspect his literary endeavours may

have been fading, anyway.

Like many writers during the Depression he was employed by the Federal

Writers’ Project, and it would seem that he did act responsibly during this

period. But he was dismissed in 1940 for having denied being a member of the

Communist Party. His old friend Ben Hecht commented, “Bogie was the sort of

Communist who would have been booted out of Moscow overnight.....He not only

angered the police but disturbed, equally, the Communist Party leaders of

New York”.

There are a number of unpublished essays that Maher has found among

Bodenheim’s surviving papers, and I can’t help wondering how much was lost

due to the chaotic nature of his life, particularly in his later years. An

essay on the German writer and novelist, Karl Jacob Wasserman possibly dates

from around 1934, and one on Dostoevsky might be from the same period. Two

others – “Should Sex Dominate Modern Literature?” and “The Relation of

Economics to Poetry” – also have roots in the 1930s.

Jack B.Moore asserts that “throughout his career Bodenheim was a vocal

anti-intellectual”, but that, of course, in no way suggests that he wasn’t

intelligent. His essays and reviews can quickly convince the reader that he

was capable of dealing with ideas, and that he had a mind able to look

beyond the ordinary and take note of the wider society and what was

happening to it. This may not have been obvious to those who only

experienced him when his life was ruled by alcohol and the need to exist on

a day-to-day basis, but the best of his essays and reviews demonstrate that,

when he could function clearly, he had something to say that was worth

listening to.

Paul Maher has performed a useful service by locating the previously

scattered material in Bughouse Dope

and presenting it in one volume. Obviously, it doesn’t include

Bodenheim’s poetry or his novels, and to round out the survey of his

activities I’d recommend Isolated

Wanderer: The Maxwell Bodenheim Reader, edited by Maher and published

“independently”, which I assume means privately. It may not be easy to find

– my copy doesn’t have a date of publication, nor any other details – but it

reprints a fair amount of his poetry, excerpts from his novels, some essays

and reviews, and a few odds and ends.

In deference to Maher’s wish to move attention away from Bodenheim’s

reputation as a misbehaving bohemian I’ve tried to limit my comments on that

aspect of his activities to the necessary. He’s too often known only because

of the nature of his death. He was murdered in 1954, along with his

common-law-wife, by a psychopath who when he was arrested said, “I ought to

get a medal.I killed two Communists”, which is, perhaps, a sad comment on

the fact that any kind of unconventional behaviour could be looked on with

suspicion in McCarthyite America. Bodenheim

deserves better than being remembered only for sensational reasons.