|

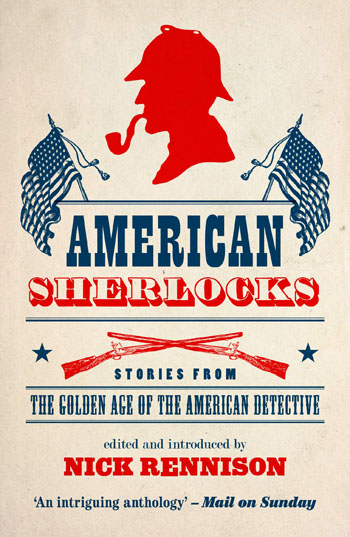

AMERICAN SHERLOCKS : STORIES FROM THE GOLDEN AGE OF THE AMERICAN

DETECTIVE

Edited by Nick Rennison

No Exit Press. 333 pages. £9.99. ISBN 978-85730-439-1

Reviewed by Jim Burns

For those of us who delight in the discovery of old detective

stories, especially those from the Victorian and Edwardian periods,

the appearance of another anthology edited by Nick Rennison can only

be welcomed. Following on from

The Rivals of Sherlock Homes

(2008), Supernatural

Sherlocks (2017), More

Rivals of Sherlock Holmes (2019), and

Sherlock’s Sisters

(2020), his new collection,

American Sherlocks, provides another sampling of the adventures

of a variety of detectives investigating murders, mysterious

disappearances, robberies, and other misdemeanours.

As the title indicates, American authors of pulp fiction are on

display. As in Britain, there were numerous magazines catering for

readers who weren’t looking for high-grade literature and instead

wanted stories that were easy-to-read, tickled the imagination a

little, but didn’t demand too much in terms of complex characters

and situations. They often did require the reader to suspend

disbelief as the detectives unravelled sometimes bizarre methods of

committing crimes, and in doing so displayed powers of deduction

beyond the capacity of most people. It seemed a standard theme that

ordinary professional policemen fumbled in the dark while those

practising, in one way or another as amateur sleuths or private

detectives, could see the light at the end of the tunnel.

One of the earliest American detective series was built around Nick

Carter. a character created by John R Coryell for a serial in the

New York Weekly in 1886.

Rennison’s notes about how Nick Carter survived well into the

late-twentieth century are fascinating. As he says, “There have been

literally thousands of Nick Carter stories, nearly all of them the

work of the mostly unidentified writers who followed Coryell”. And

the portrait of Carter was altered to meet changing tastes as he

developed from “a dime novel hero to Sherlockian consulting

detective to hardboiled private eye…….and was even relaunched as a

James Bond-style secret agent” in the 1960s. The story that Rennison

uses was published in 1914 and involves an attractive actress, a mad

doctor, a prison breakout, hypnotism, and much rascally behaviour.

It’s notable for a conclusion which involves several pages revolving

around a detailed description of a fight between Carter, accompanied

by an assistant, and a gang of miscreants.

It might give an indication of the widespread fame of the Carter

stories, and the audience they catered for, if I mention that, in

another story, Clinton H Stagg’s “The Flying Death”, a young boy who

is a kind of protégé of the “problemist”, as the detective is

called, is said to see Carter as one of his fictional heroes.

Thornley Colton, the detective, is blind, a fact that, as with Max

Carados in the stories by the English author, Ernest Bramah,

heightens his other senses. Combined with his analytical

intelligence this enables him to come up with solutions to crimes

that have baffled other people. In “The Flying Death” he deduces how

a pistol can be fired without anyone being physically near it to

pull the trigger, or having attached a cord to do it.

I have to admit that my

disbelief really did kick in with this piece. It’s in this story,

too, that the sneering villain, explaining how he carried out his

crime, says that “there’s Indian blood in me, mixed with the Irish”,

as if it explains how he could be so clever and so devious. Racial

stereotypes were often a feature of writing at this time, and not

only in pulp fiction.

It’s possible to see them at work in the use of “wop” in more than

one story to refer to Italians. Jacques Futrelle’s “The Problem of

the Opera Box” sees an Italian exacting vengeance with a knife, a

weapon favoured by Latins and the like, but disdained by sturdy

Anglo-Saxons. Or in Rodrigues Ottolengui’s “Mr Barnes and Mr

Mitchel” where there is a reference to a “sneaking Mexican”. The

story concerns a rare jewel, the Montezuma Emerald, the theft of

such items being a fairly standard ploy in detective fiction. George

Barton’s “Adventure of the Cleopatra Necklace”, for example, has his

detective, Bromley Barnes, tracking down the item in question. I was

intrigued by Rennison’s notes about Ottolengui who “devoted most of

his energies to his career as a dentist”, but also wrote four novels

and a number of short stories. He pioneered “the use of x-rays in

orthodontics” and edited a dental journal, and when he died in 1937

the obituaries focused more on those facts than on his fiction.

Which is, perhaps, understandable. Unlike now, little serious

attention was then paid to crime fiction, especially of the popular

variety.

The racial stereotyping would upset people today, and certainly

incline publishers to persuade their authors to delete any signs of

it from their work. And what would be the reaction to some of the

scenes in Arthur B Reeves’

“The Azure Ring”, where his hero, Craig Kennedy, described as

“the scientific detective”, blithely uses a cat and a couple of

white mice in his experiments to determine the lethal nature of a

substance he suspects has been used to kill a young couple? To prove

his point the animals die. I suppose it’s only fair to say that

Kennedy, to reach his final conclusion regarding the quantity of the

material required to kill a human, is prepared to subject himself to

the test. He does so with a near-fatal result. But I can imagine

animal lovers being concerned about the cat and mice, and possibly

suggesting that the man had voluntarily used himself as a guinea

pig, knowing full well the risks involved, whereas the animals had

no choice in the matter.

Reeves is the one writer with two stories in the book, the other

story being “The Mystery of the Stolen Da Vinci”, with the female

detective, Clare Kendall, on the hunt for a painting said to be “the

companion piece to Mona Lisa,

painted about the same time”. The thieves turn out to be a couple of

foreigners, again Italians, which could cause some people to think

that, bearing in mind where the picture was painted, it was just

being removed from the possession of a vulgar millionaire, and

returned to its rightful home. But I doubt that the thieves were

patriots who had that in mind. Rennison points out that the story

was written around the time that the

Mona Lisa had been stolen

from the Louvre, so had some contemporary relevance. It’s also worth

noting that the detective makes use of a telegraphone, a device

which works along the lines of a tape recorder. It was an actual

machine, invented by Valdemar Poulsen, known as the “Danish Edison”.

The contemporary crops up in Anthony M Rud’s “The Affair at Steffen

Shoals”, which lets us see how Jigger Masters and his friend foil

some spies who are passing secrets

to the Germans. The story was presumably written during the

period – 1917/18 – when the United States was involved in the First

World War. The secrets are to do with plans for a new kind of gas

that can be used with terrifying effect and must not be allowed to

fall into enemy hands. Masters manages to outwit the spy and his

gang and help sink a German submarine into the bargain. It’s

interesting in the way that it relates to the fact that there were

numerous pro-German sympathisers in the United States owing to the

large numbers of immigrants from that country.

Rennison mentions that old, supposedly humorous detective tales tend

not to survive too well, but I did find Carolyn Wells’s

“Christabel’s Crystal” quite entertaining as a gentle send-up of the

Sherlock Homes–style story. Its female narrator, Elinor Frost,

admits to not being familiar with different brands of cigar ash

which, she says, are often key clues when attempting to identify who

has been present in a room.

There’s also an English aristocrat who, like Holmes, can

pinpoint someone’s background from a quick glance at his complexion

or his clothes. It’s mildly amusing, which is more than can be said

for the laboured humour of Ellis Parker Butler’s “Philo

Gubb’s Greatest Case”, where Philo, a paper-hanger by profession,

and a keen amateur detective, adopts a number of disguises that fool

no-one. It’s easy to see how it would have appealed at the time in

the context of a casually-read magazine, but it has dated badly.

Carolyn Wells is one of only two women writers in

American Sherlocks, the

other being Anna Katharine Green. Her detective, Violent Strange, is

a well-heeled young woman who moves in high society circles in New

York, but also accepts assignments from a detective agency, though

she’s fussy about which investigations she’ll accept. She’s

reluctant to take on the case of “The Second Bullet”, but eventually

agrees to meet the grieving widow whose husband and child have died

in a mysterious shooting incident. There’s a somewhat implausible

ending to the story, but Green’s writing is competent enough to keep

the narrative moving and perhaps persuade the reader that it could

have happened that way.

I think “competent writing” might well be the correct way to

describe the better-told stories. None attain the heights of great

literature, but they often have a drive and energy that moves the

narrative along in a convincing manner. Hugh Cosgrove Weir’s

“Cinderella’s Slipper” spotlights his engaging heroine, Madelyn

Mack, who is known to chew cola berries to stimulate her thinking

when the situation requires intense wakefulness and concentration. I

had come across this story earlier, in Hugh Greene’s

The American Rivals of

Sherlock Holmes (Penguin, 1978), but it’s good to have it in

print again. The writing is crisp and clean, with few wasted words.

A writer I’ve never encountered before is Samuel Gardenhire, “a

Missouri-born lawyer who turned to writing fiction in middle-age”.

He produced eight stories, one of which, “The Park Slope Mystery”,

has his sleuth, Ledroit Conners, looking into a bizarre shooting in

a highly-respectable household. I know that questions have sometimes

been raised about Sherlock Holmes’s attitude towards women, but what

are we to make of Conners who says, “I endeavour to avoid women”.

His friend says “I glanced again at his pictures, where sylph and

siren, Venus in nature with Venus à la mode showed every phase of

beauty to the eye”. Conners, noting his friend’s action, says:

“These do not count. You recall the temptation of St Anthony? I hold

discipline to be good for a man. These I may love – none other”.

Whatever their qualities in terms of the writing, the stories in

American Sherlocks always

have an entertainment value. And Rennison’s introduction and notes

add to the appeal of a book like this. Who can resist reading about

Charles Felton Pidgin, who created Quincy Adams Sawyer, “a

professional private investigator, clearly influenced by Sherlock

Holmes”. Pidgin himself turned his hand towards various activities –

a statistician, a writer of musical comedies for the stage, and an

inventor, plus writing “more than a dozen novels”. His story, “The

Affair of Lamson’s Cook”, has a neat twist in the tail.

Even if we only look at the late-Victorian and Edwardian years,

there must be hundreds of detective stories buried in now-forgotten

magazines and newspapers. Many of them may not deserve to be dug out

and reprinted. But some can still interest and intrigue as their

sleuths, both men and women, endeavour to hold the forces of evil at

bay. Let’s hope that Nick Rennison will come up with more examples.

|